Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee | |

|---|---|

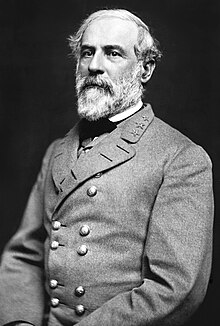

Lee in 1864 | |

| Birth name | Robert Edward Lee |

| Nickname(s) |

|

| Born | January 19, 1807 Stratford Hall, Westmoreland County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | October 12, 1870 (aged 63) Lexington, Virginia, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles / wars |

|

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

| Relations | Lee family |

| Signature | |

| General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate States | |

| In office February 6, 1865 – April 12, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| 1st President of Washington and Lee University | |

| In office 1865–1870 | |

| Preceded by | George Junkin (Washington College) |

| Succeeded by | Custis Lee |

| Superintendent of the United States Military Academy | |

| In office 1852–1855 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Brewerton |

| Succeeded by | John G. Barnard |

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, toward the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Northern Virginia, the Confederacy's most powerful army, from 1862 until its surrender in 1865, earning a reputation as a skilled tactician.

A son of Revolutionary War officer Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee III, Lee was a top graduate of the United States Military Academy and an exceptional officer and military engineer in the United States Army for 32 years. He served across the United States, distinguished himself extensively during the Mexican–American War, and was Superintendent of the United States Military Academy. He married Mary Anna Custis, great-granddaughter of George Washington's wife Martha. While he opposed slavery from a philosophical perspective, he supported its legality and held hundreds of slaves. When Virginia declared its secession from the Union in 1861, Lee chose to follow his home state, despite his desire for the country to remain intact and an offer of a senior Union command. During the first year of the Civil War, he served in minor combat operations and as a senior military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia in June 1862 during the Peninsula Campaign following the wounding of Joseph E. Johnston. He succeeded in driving the Union Army of the Potomac under George B. McClellan away from the Confederate capital of Richmond during the Seven Days Battles, but he was unable to destroy McClellan's army. Lee then overcame Union forces under John Pope at the Second Battle of Bull Run in August. His invasion of Maryland that September ended with the inconclusive Battle of Antietam, after which he retreated to Virginia. Lee won two major victories at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville before launching a second invasion of the North in the summer of 1863, where he was decisively defeated at the Battle of Gettysburg by the Army of the Potomac under George Meade. He led his army in the minor and inconclusive Bristoe Campaign that fall before General Ulysses S. Grant took command of Union armies in the spring of 1864. Grant engaged Lee's army in bloody but inconclusive battles at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania before the lengthy Siege of Petersburg, which was followed in April 1865 by the capture of Richmond and the destruction of most of Lee's army, which he finally surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House.

In 1865, Lee became president of Washington College, now Washington and Lee University, in Lexington, Virginia; as president of the college, he supported reconciliation between the North and South. Lee accepted the termination of slavery provided for by the Thirteenth Amendment, but opposed racial equality for African Americans. After his death in 1870, Lee became a cultural icon in the South and is largely hailed as one of the Civil War's greatest generals. As commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, he fought most of his battles against armies of significantly larger size, and managed to win many of them. Lee built up a collection of talented subordinates, most notably James Longstreet, Stonewall Jackson, and J. E. B. Stuart, who along with Lee were critical to the Confederacy's battlefield success.[1][2] In spite of his successes, his two major strategic offensives into Union territory both ended in failure. Lee's aggressive and risky tactics, especially at Gettysburg, which resulted in high casualties at a time when the Confederacy had a shortage of manpower, have come under criticism.[3] His legacy, and his views on race and slavery, have been the subject of continuing debate and historical controversy.

Early life and education

Lee was born at Stratford Hall Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia, to Henry Lee III and Anne Hill Carter Lee on January 19, 1807.[4] His ancestor, Richard Lee I, emigrated from Shropshire, England, to Virginia in 1639.[5]

Lee's father suffered severe financial reverses from failed investments[6] and was put in debtors' prison. Soon after his release the following year, the family moved to the city of Alexandria which at the time was still part of the District of Columbia, which retroceded back to Virginia in 1847, both because there were then high quality local schools there, and because several members of Anne's extended family lived nearby. In 1811, the family, including the newly born sixth child, Mildred, moved to a house on Oronoco Street.[7]

In 1812 Lee's father moved permanently to the West Indies.[8] Lee attended Eastern View, a school for young gentlemen, in Fauquier County, Virginia, and then at the Alexandria Academy, free for local boys, where he showed an aptitude for mathematics. Although brought up to be a practicing Christian, he was not confirmed in the Episcopal Church until age 46.[9]

Anne Lee's family was often supported by a relative, William Henry Fitzhugh, who owned the Oronoco Street house and allowed the Lees to stay at his country home Ravensworth. Fitzhugh wrote to United States Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, urging that Robert be given an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Fitzhugh had young Robert deliver the letter.[10] Lee entered West Point in the summer of 1825. At the time, the focus of the curriculum was engineering; the head of the United States Army Corps of Engineers supervised the school and the superintendent was an engineering officer. Cadets were not permitted leave until they finished two years of study and were rarely allowed off the academy grounds. Lee graduated second in his class behind Charles Mason[11] (who resigned from the Army a year after graduation). Lee did not incur any demerits during his four-year course of study, a distinction shared by only five of his 45 classmates. In June 1829, Lee was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.[12] After graduation, while awaiting assignment, he returned to Virginia to find his mother on her deathbed; she died at Ravensworth on July 26, 1829.[13]

Military engineer career

On August 11, 1829, Brigadier General Charles Gratiot ordered Lee to Cockspur Island, Georgia. The plan was to build a fort on the marshy island which would command the outlet of the Savannah River. Lee was involved in the early stages of construction as the island was being drained and built up.[14] In 1831, it became apparent that the existing plan to build what became known as Fort Pulaski would have to be revamped, and Lee was transferred to Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula (today in Hampton, Virginia).[15]

While home in the summer of 1829, Lee had apparently courted Mary Custis whom he had known as a child. Lee obtained permission to write to her before leaving for Georgia, though Mary Custis warned Lee to be "discreet" in his writing, as her mother read her letters, especially from men.[16] Custis refused Lee the first time he asked to marry her; her father did not believe the son of the disgraced Light-Horse Harry Lee was a suitable man for his daughter.[17] She accepted him with her father's consent in September 1830, while he was on summer leave,[18] and the two were wed on June 30, 1831.[19]

Lee's duties at Fort Monroe were varied, typical for a junior officer, and ranged from budgeting to designing buildings.[20] Although Mary Lee accompanied her husband to Hampton Roads, she spent about a third of her time at Arlington, though the couple's first son, Custis Lee was born at Fort Monroe. Although the two were by all accounts devoted to each other, they were different in character: Robert Lee was tidy and punctual, qualities his wife lacked. Mary Lee also had trouble switching from being a rich man's daughter to having to manage a household with only one or two enslaved people.[21] Beginning in 1832, Robert Lee had a close but platonic relationship with Harriett Talcott, wife of his fellow officer Andrew Talcott.[22]

Life at Fort Monroe was marked by conflicts between artillery and engineering officers. Eventually, the War Department transferred all engineering officers away from Fort Monroe, except Lee, who was ordered to take up residence on the artificial island of Rip Raps across the river from Fort Monroe, where Fort Wool would eventually rise, and continue work to improve the island. Lee duly moved there, then discharged all workers and informed the War Department he could not maintain laborers without the facilities of the fort.[23] In 1834, Lee was transferred to Washington as General Gratiot's assistant.[24] Lee had hoped to rent a house in Washington for his family, but was not able to find one; the family lived at Arlington, though Lieutenant Lee rented a room at a Washington boarding house for when the roads were impassable.[25] In mid-1835, Lee was assigned to assist Andrew Talcott in surveying the southern border of Michigan.[26] While on that expedition, he responded to a letter from an ill Mary Lee, which had requested he come to Arlington, "But why do you urge my immediate return, & tempt one in the strongest manner[?]... I rather require to be strengthened & encouraged to the full performance of what I am called on to execute."[27] Lee completed the assignment and returned to his post in Washington, finding his wife ill at Ravensworth. Mary Lee, who had recently given birth to their second child, remained bedridden for several months. In October 1836, Lee was promoted to first lieutenant.[28]

Lee served as an assistant in the chief engineer's office in Washington, D.C. from 1834 to 1837, but spent the summer of 1835 helping to lay out the state line between Ohio and Michigan. As a first lieutenant of engineers in 1837, he supervised the engineering work for St. Louis harbor and for the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Among his projects was the mapping of the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi above Keokuk, Iowa, where the Mississippi's mean depth of 2.4 feet (0.7 m) was the upper limit of steamboat traffic on the river. His work there earned him a promotion to captain. Around 1842, Captain Robert E. Lee arrived as Fort Hamilton's post engineer.[29]

Marriage and family

While Lee was stationed at Fort Monroe, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis (1807–1873), great-granddaughter of Martha Washington by her first husband Daniel Parke Custis, and step-great-granddaughter of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Mary was the only surviving child of George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington's stepgrandson, and Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, daughter of William Fitzhugh[30] and Ann Bolling Randolph. Robert and Mary married on June 30, 1831, at Arlington House, her parents' house just across the Potomac from Washington. The 3rd U.S. Artillery served as honor guard at the marriage. They eventually had seven children, three boys and four girls:[31]

- George Washington Custis Lee (Custis, "Boo"); 1832–1913; served as major general in the Confederate Army and aide-de-camp to President Jefferson Davis, captured during the Battle of Sailor's Creek; unmarried

- Mary Custis Lee (Mary, "Daughter"); 1835–1918; unmarried

- William Henry Fitzhugh Lee ("Rooney"); 1837–1891; served as major general in the Confederate Army (cavalry); married twice; surviving children by second marriage

- Anne Carter Lee (Annie); June 18, 1839 – October 20, 1862; died of typhoid fever, unmarried

- Eleanor Agnes Lee (Agnes); 1841 – October 15, 1873; died of tuberculosis, unmarried

- Robert Edward Lee, Jr. (Rob); 1843–1914; served in the Confederate Army, first as a private in the Rockbridge Artillery, later as a Captain on the staff of his brother Rooney; married twice; surviving children by second marriage

- Mildred Childe Lee (Milly, "Precious Life"); 1846–1905; unmarried

All the children survived him except for Annie, who died in 1862. They are all buried with their parents in the crypt of the University Chapel at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia.[32]

Lee was a great-great-great-grandson of William Randolph and a great-great-grandson of Richard Bland.[33] Fitzhugh Lee (1835–1905), a Confederate general and later a United States Army general in the Spanish–American War, was Lee's nephew. Lee was a second cousin of Helen Keller's grandmother,[34] and was a distant relative of Admiral Willis Augustus Lee.[35]

On May 1, 1864, General Lee was present at the baptism of General A. P. Hill's daughter, Lucy Lee Hill, to serve as her godfather. This is referenced in the painting Tender is the Heart by Mort Künstler.[36] He was also the godfather of actress and writer Odette Tyler, the daughter of Brigadier General William Whedbee Kirkland.[37]

Mexican–American War

Lee distinguished himself in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). He was one of Winfield Scott's chief aides in the march from Veracruz to Mexico City.[38] He was instrumental in several American victories through his personal reconnaissance as a staff officer; he found routes of attack that the Mexicans had not defended because they thought the terrain was impassable.

He was promoted to brevet major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847.[39] He also fought at Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec and was wounded at the last. By the end of the war, he had received additional brevet promotions to lieutenant colonel and colonel, but his permanent rank was still captain of engineers, and he would remain a captain until his transfer to the cavalry in 1855.

For the first time, Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant met and worked with each other during the Mexican–American War. Close observations of their commanders constituted a learning process for both Lee and Grant.[40] The Mexican–American War concluded on February 2, 1848.

After the Mexican War, Lee spent three years at Fort Carroll in Baltimore harbor. During this time, his service was interrupted by other duties, among them surveying and updating maps in Florida. Cuban revolutionary Narciso López intended to forcibly liberate Cuba from Spanish rule. In 1849, searching for a leader for his filibuster expedition, he approached Jefferson Davis, then a United States senator. Davis declined and suggested Lee, who also declined. Both decided it was inconsistent with their duties.[41][42]

Early 1850s: West Point and Texas

The 1850s were a difficult time for Lee, with his long absences from home, the increasing disability of his wife, troubles in taking over the management of a large slave plantation, and his often morbid concern with his personal failures.[43]

In 1852, Lee was appointed Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point.[44] He was reluctant to enter what he called a "snake pit", but the War Department insisted and he obeyed. His wife occasionally came to visit. During his three years at West Point, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee improved the buildings and courses and spent much time with the cadets. Lee's oldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, attended West Point during his tenure. Custis Lee graduated in 1854, first in his class.[45]

Lee was enormously relieved to receive a long-awaited promotion as second-in-command of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment in Texas in 1855. It meant leaving the Engineering Corps and its sequence of staff jobs for the combat command he truly wanted. He served under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston at Camp Cooper, Texas; their mission was to protect settlers from attacks by the Apache and the Comanche.

Late 1850s: Arlington plantation and the Custis slaves

In 1857, his father-in-law George Washington Parke Custis died, creating a serious crisis when Lee took on the burden of executing the will. Custis's estate encompassed vast landholdings and hundreds of slaves but also massive debts; the will required people formerly enslaved by Custis "to be emancipated by my executors in such manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper, the said emancipation to be accomplished in not exceeding five years from the time of my decease".[46] The estate was in disarray, and the plantations had been poorly managed and were losing money.[47] Lee tried to hire an overseer to handle the plantation in his absence, writing to his cousin, "I wish to get an energetic honest farmer, who while he will be considerate & kind to the negroes, will be firm & make them do their duty."[48] But Lee failed to find a man for the job, and had to take a two-year leave of absence from the army to run the plantation himself.

Lee's more strict expectations and harsher punishments of the slaves on Arlington plantation nearly led to a revolt, since many of the enslaved people had been given to understand that they were to be made free as soon as Custis died, and protested angrily at the delay.[49] In May 1858, Lee wrote to his son Rooney, "I have had some trouble with some of the people. Reuben, Parks & Edward, in the beginning of the previous week, rebelled against my authority—refused to obey my orders, & said they were as free as I was, etc., etc.—I succeeded in capturing them & lodging them in jail. They resisted till overpowered & called upon the other people to rescue them."[48] Less than two months after they were sent to the Alexandria jail, Lee decided to remove these three men and three female house slaves from Arlington, and sent them under lock and key to the slave-trader William Overton Winston in Richmond, who was instructed to keep them in jail until he could find "good & responsible" enslavers to work them until the end of the five-year period.[48]

By 1860, only one family of slaves was left intact on the estate. Some of the families had been together since their time at Mount Vernon.[50]

The Norris case

In 1859, three slaves at Arlington—Wesley Norris, his sister Mary, and a cousin of theirs—fled for the North, but were captured a few miles from the Pennsylvania border and forced to return to the plantation. On June 24, 1859, the anti-slavery newspaper New York Daily Tribune published two anonymous letters (dated June 19[51] and June 21[52]), each claiming to have heard that Lee had the Norrises whipped, and that the overseer refused to whip the woman but that Lee took the whip and flogged her personally. Lee privately wrote to his son Custis that "The N. Y. Tribune has attacked me for my treatment of your grandfather's slaves, but I shall not reply. He has left me an unpleasant legacy."[53]

Wesley Norris himself spoke out about the incident after the war, in an 1866 interview printed in an abolitionist newspaper, the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Norris said that after they had been captured, and forced to return to Arlington, Lee told them that "he would teach us a lesson we would not soon forget". According to Norris, Lee had the overseer tie the three of them firmly to posts, and ordered them whipped: 50 lashes for the men and 20 for Mary Norris. Norris claimed that Lee encouraged the whipping, and that when the overseer refused to do it, called in the county constable to do it instead. Unlike the anonymous letter writers, he does not state that Lee himself whipped any of the enslaved people. According to Norris, Lee "frequently enjoined [Constable] Williams to 'lay it on well', an injunction which he did not fail to heed; not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done."[49][54]

The Norris men were then sent by Lee's agent to work on the railroads in Virginia and Alabama. According to the interview, Norris was sent to Richmond in January 1863 "from which place I finally made my escape through the rebel lines to freedom". But Federal authorities reported that Norris came within their lines on September 5, 1863, and that he "left Richmond ..with a pass from General Custis Lee."[55][56] Lee freed the people enslaved by Custis, including Wesley Norris, after the end of the five-year period in the winter of 1862, filing the deed of manumission on December 29, 1862.[57][58]

Biographers of Lee have differed over the credibility of the account of the punishment as described in the letters in the Tribune and in Norris's personal account. They broadly agree that Lee sought to recapture a group of slaves who had escaped, and that, after recapturing them, he hired them out off of the Arlington plantation as a punishment; however, they disagree over the likelihood that Lee flogged them, and over the charge that he personally whipped Mary Norris. In 1934, Douglas S. Freeman described the incident as "Lee's first experience with the extravagance of irresponsible antislavery agitators" and asserted that "There is no evidence, direct or indirect, that Lee ever had them or any other Negroes flogged. The usage at Arlington and elsewhere in Virginia among people of Lee's station forbade such a thing."[59]

In 2000, Michael Fellman, in The Making of Robert E. Lee, found the claims that Lee had personally whipped Mary Norris "extremely unlikely", but found it not at all unlikely that Lee had ordered the runaways whipped: "corporal punishment (for which Lee substituted the euphemism "firmness") was [believed to be] an intrinsic and necessary part of slave discipline. Although it was supposed to be applied only in a calm and rational manner, overtly physical domination of slaves, unchecked by law, was always brutal and potentially savage."[60]

Lee biographer Elizabeth Brown Pryor concluded in 2008 that "the facts are verifiable", based on "the consistency of the five extant descriptions of the episode (the only element that is not repeatedly corroborated is the allegation that Lee gave the beatings himself), as well as the existence of an account book that indicates the constable received compensation from Lee on the date that this event occurred".[61][62]

In 2014, Michael Korda wrote that "Although these letters are dismissed by most of Lee's biographers as exaggerated, or simply as unfounded abolitionist propaganda, it is hard to ignore them [...] It seems incongruously out of character for Lee to have whipped a slave woman himself, particularly one stripped to the waist, and that charge may have been a flourish added by the two correspondents; it was not repeated by Wesley Norris when his account of the incident was published in 1866 [...] [A]lthough it seems unlikely that he would have done any of the whipping himself, he may not have flinched from observing it to make sure his orders were carried out exactly."[63]

Lee's views on race and slavery

Several historians have noted what they consider the contradictory nature of Lee's beliefs and actions concerning race and slavery. While Lee protested he had sympathetic feelings for blacks, they were subordinate to his own racial identity.[64] While Lee held slavery to be an evil institution, he also saw some benefit to blacks held in slavery.[65] While Lee helped assist individual slaves reach freedom in Liberia, and provided for their emancipation in his own will,[66] he believed slaves should be eventually freed in a general way only at some unspecified future date as a part of God's purpose.[64][67] Slavery for Lee was a moral and religious issue, and not one that would yield to political solutions.[68] Emancipation would sooner come from Christian impulse among slave masters before "storms and tempests of fiery controversy" such as was occurring in "Bleeding Kansas".[64] Countering Southerners who argued for slavery as a positive good, Lee in his well-known analysis of slavery from an 1856 letter (see below) called it a moral and political evil. While both Lee and his wife were disgusted with slavery, they also defended it against abolitionist demands for immediate emancipation for all enslaved.[69]

Lee argued that slavery was bad for white people,[70] claiming that he found slavery bothersome and time-consuming as an everyday institution to run. In an 1856 letter to his wife, he maintained that slavery was a great evil, but primarily due to adverse impact that it had on white people:[71]

In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.[72]

Before leaving to serve in Mexico, Lee had written a will providing for the manumission of the slaves he owned, "a woman and her children inherited from his mother and apparently leased to his father-in-law and later sold to him".[73] Lee's father-in-law, G. W. Parke Custis, was a member of the American Colonization Society, which was formed to gradually end slavery by establishing a free republic in Liberia for African-Americans, and Lee assisted several formerly enslaved people to emigrate there. Also, according to historian Richard B. McCaslin, Lee was a gradual emancipationist, denouncing extremist proposals for the immediate abolition of slavery. Lee rejected what he called evilly motivated political passion, fearing a civil and servile war from precipitous emancipation.[74]

Historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor offered an alternative interpretation of Lee's voluntary manumission of slaves in his will, and assisting slaves to a life of freedom in Liberia, seeing Lee as conforming to a "primacy of slave law". She wrote that Lee's private views on race and slavery,

- "which today seem startling, were entirely unremarkable in Lee's world. No visionary, Lee nearly always tried to conform to accepted opinions. His assessment of black inferiority, of the necessity of racial stratification, the primacy of slave law, and even a divine sanction for it all, was in keeping with the prevailing views of other moderate slaveholders and a good many prominent Northerners."[75]

In 1857, George Custis died, leaving Robert Lee as the executor of his estate, which included nearly 200 slaves.[76] In his will, Custis said the enslaved people were to be freed within five years of his death. On taking on the role of administrator for the Parke Custis will, Lee used a provision to retain them in slavery to produce income for the estate to retire debt.[77] Lee did not welcome the role of planter while administering the Custis properties at Romancoke, another nearby the Pamunkey River and Arlington; he rented the estate's mill. While all the estates prospered under his administration, Lee was unhappy at direct participation in slavery as a hated institution.[78]

Even before what Michael Fellman called a "sorry involvement in actual slave management", Lee judged the experience of white mastery to be a greater moral evil to the white man than blacks suffering under the "painful discipline" of slavery which introduced Christianity, literacy and a work ethic to the "heathen African".[79] Columbia University historian Eric Foner notes that:

- Lee "was not a pro-slavery ideologue. But I think equally important is that, unlike some white southerners, he never spoke out against slavery"[80]

By the time of Lee's career in the U.S. Army, the officers of West Point stood aloof from political-party and sectional strife on such issues as slavery, as a matter of principle, and Lee adhered to the precedent.[81][82] He considered it his patriotic duty to be apolitical while in active Army service,[83][84][85] and Lee did not speak out publicly on the subject of slavery prior to the Civil War.[86][87] Before the outbreak of the War, in 1860, Lee voted for Southern Democratic nominee and incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge, who was the pro-slavery candidate in the 1860 presidential election and had supported the Lecompton Constitution for Kansas, rather than Constitutional Union Party nominee John Bell, the Southern Unionist candidate who won Virginia and voted against the admission of Kansas under the Lecompton Constitution as the United States Senator from Tennessee.[88][a]

Lee himself enslaved a small number of people in his lifetime and considered himself a paternalistic master.[88] There are various historical and newspaper hearsay accounts of Lee's personally whipping a slave, but they are not direct eyewitness accounts. He was definitely involved in administering the day-to-day operations of a plantation and was involved in the recapture of runaway slaves.[89] One historian noted that Lee separated families of enslaved people, something that prominent enslaving families in Virginia such as Washington and Custis did not do.[70] On December 29, 1862, the last day he was allowed to legally retain them, Lee finally freed all the enslaved people his wife had inherited from George Custis (in accordance with the Custis will).[90] Before this, Lee had petitioned the courts to keep people enslaved by Custis longer than the five years allotted in Custis' will, since the estate was still in debt, but the courts rejected his appeals.[76] In 1866, one of the people formerly enslaved by Lee, Wesley Norris, charged that Lee personally beat him and other slaves harshly after they had tried to run away from Arlington.[91] Lee never publicly responded to this charge, but privately told a friend "There is not a word of truth in it ... No servant, soldier, or citizen, that was ever employed by me can with truth charge me with bad treatment."[92]

Foner writes that "Lee's code of gentlemanly conduct did not seem to apply to blacks" during the War. He did not stop his soldiers from kidnapping free black farmers and selling them into slavery.[80] Princeton University historian James M. McPherson noted that Lee initially rejected a prisoner exchange between the Confederacy and the Union when the Union demanded that black Union soldiers be included.[70] Lee did not accept the swap until a few months before the Confederacy's surrender.[70] He also called the Emancipation Proclamation "a savage and brutal policy...which leaves us no alternative but success or degradation worse than death".[93]

As the war dragged on and Lee's losses mounted, he eventually advocated enlisting enslaved people in the Confederate army in exchange for freedom. However, he came to this position with great reluctance. In an 1865 letter to his friend Andrew Hunter, he wrote: "Considering the relation of master and slave, controlled by humane laws and influenced by Christianity and an enlightened public sentiment, as the best that can exist between the white and black races while intermingled as at present in this country, I would deprecate any sudden disturbance of that relation unless it be necessary to avert a greater calamity to both. I should therefore prefer to rely upon our white population to preserve the ratio between our forces and those of the enemy, which experience has shown to be safe. But in view of the preparations of our enemies, it is our duty to provide for continued war and not for a battle or a campaign, and I fear that we cannot accomplish this without overtaxing the capacity of our white population."[94]

After the War, Lee told a congressional committee that blacks were "not disposed to work" and did not possess the intellectual capacity to vote and participate in politics.[90] Lee also said to the committee that he hoped that Virginia could "get rid of them", referring to blacks.[90] While not politically active, Lee defended Lincoln's successor Andrew Johnson's approach to Reconstruction, which according to Foner, "abandoned the former slaves to the mercy of governments controlled by their former owners".[95] According to Foner, "A word from Lee might have encouraged white Southerners to accord blacks equal rights and inhibited the violence against the freed people that swept the region during Reconstruction, but he chose to remain silent."[90] Lee was also urged to condemn the white-supremacy[96] organization Ku Klux Klan, but opted to remain silent.[88]

In the generation following the war, Lee, though he died just a few years later, became a central figure in the Lost Cause interpretation of the war. The argument that Lee had always opposed slavery, and freed the people enslaved by his wife, helped maintain his stature as a symbol of Southern honor and national reconciliation.[88]

Harpers Ferry and return to Texas, 1859–1861

Both Harpers Ferry and the secession of Texas were monumental events leading up to the Civil War. Robert E. Lee was at both events. Lee initially remained loyal to the Union after Texas seceded.[97]

Harpers Ferry

John Brown led a band of 21 abolitionists who seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859, hoping to incite a slave rebellion. President James Buchanan gave Lee command of detachments of militia, soldiers, and United States Marines, to suppress the uprising and arrest its leaders.[98] By the time Lee arrived that night, the militia on the site had surrounded Brown and his hostages. At dawn, Brown refused the demand for surrender. Lee attacked, and Brown and his followers were captured after three minutes of fighting. Lee's summary report of the episode shows Lee believed it "was the attempt of a fanatic or madman". Lee said Brown achieved "temporary success" by creating panic and confusion and by "magnifying" the number of participants involved in the raid.[99]

Texas

In 1860, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee relieved Major Heintzelman at Fort Brown, and the Mexican authorities offered to restrain "their citizens from making predatory descents upon the territory and people of Texas ... this was the last active operation of the Cortina War". Rip Ford, a Texas Ranger at the time, described Lee as "dignified without hauteur, grand without pride ... he evinced an imperturbable self-possession, and a complete control of his passions ... possessing the capacity to accomplish great ends and the gift of controlling and leading men".[100]

When Texas seceded from the Union in February 1861, General David E. Twiggs surrendered all the American forces (about 4,000 men, including Lee, and commander of the Department of Texas) to the Texans. Twiggs immediately resigned from the U.S. Army and was made a Confederate general. Lee went back to Washington and was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment of Cavalry in March 1861. Lee's colonelcy was signed by the new president, Abraham Lincoln. Three weeks after his promotion, Colonel Lee was offered a senior command (with the rank of Major General) in the expanding Army to fight the Southern States that had left the Union. Fort Mason, Texas, was Lee's last command with the United States Army.[101]

Civil War

Resignation from United States Army

Unlike many Southerners who expected a glorious war, Lee correctly predicted it as protracted and devastating.[102] He privately opposed the new Confederate States of America in letters in early 1861, denouncing secession as "nothing but revolution" and an unconstitutional betrayal of the efforts of the Founding Fathers. Writing to George Washington Custis in January, Lee stated:

The South, in my opinion, has been aggrieved by the acts of the North, as you say. I feel the aggression, and am willing to take every proper step for redress. It is the principle I contend for, not individual or private benefit. As an American citizen, I take great pride in my country, her prosperity and institutions, and would defend any State if her rights were invaded. But I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union. It would be an accumulation of all the evils we complain of, and I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation. I hope, therefore, that all constitutional means will be exhausted before there is a resort to force. Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our Constitution never exhausted so much labor, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation, and surrounded it with so many guards and securities, if it was intended to be broken by every member of the Confederacy at will. It was intended for "perpetual union", so expressed in the preamble, and for the establishment of a government, not a compact, which can only be dissolved by revolution, or the consent of all the people in convention assembled.[103]

Despite opposing secession, Lee said in January that "we can with a clear conscience separate" if all peaceful means failed. He agreed with secessionists in most areas, rejecting the Northern abolitionists' criticisms and their prevention of the expansion of slavery to the new western territories, and fear of the North's larger population. Lee supported the Crittenden Compromise, which would have constitutionally protected slavery.[104]

Lee's objection to secession was ultimately outweighed by a sense of personal honor, reservations about the legitimacy of a strife-ridden "Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets", and his duty to defend his native Virginia if attacked.[103] He was asked while leaving Texas by a lieutenant if he intended to fight for the Confederacy or the Union, to which Lee replied, "I shall never bear arms against the Union, but it may be necessary for me to carry a musket in the defense of my native state, Virginia, in which case I shall not prove recreant to my duty".[105][104]

Although Virginia had the most slaves of any state, it was more similar to Maryland, which stayed in the Union, than to the Deep South; a convention voted against secession in early 1861. Winfield Scott, commanding general of the Union Army and Lee's mentor, told Lincoln he wanted him for a top command, telling Secretary of War Simon Cameron that he had "entire confidence" in Lee. Lee accepted a promotion to colonel of the 1st Cavalry Regiment on March 28, again swearing an oath to the United States.[106][104] Meanwhile, Lee ignored an offer of command from the Confederacy. After Lincoln's call for troops to put down the rebellion, a second Virginia convention in Richmond voted to secede[107] on April 17, and a May 23 referendum would likely ratify the decision. That night Lee dined with brother Smith and cousin Phillips, naval officers. Because of Lee's indecision, Phillips went to the War Department the next morning to warn that the Union might lose his cousin if the government did not act quickly.[104]

In Washington that day,[102] Lee was offered by presidential advisor Francis P. Blair a role as major general to command the defense of the national capital. He replied:

Mr. Blair, I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four millions of slaves in the South I would sacrifice them all to the Union; but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?[107]

Lee immediately went to Scott, who tried to persuade him that Union forces would be large enough to prevent the South from fighting, so he would not have to oppose his state; Lee disagreed. When Lee asked if he could go home and not fight, the fellow Virginian said that the army did not need equivocal soldiers and that if he wanted to resign, he should do so before receiving official orders. Scott told him that Lee had made "the greatest mistake of your life".[104]

Lee agreed that to avoid dishonor he had to resign before receiving unwanted orders. While historians have usually called his decision inevitable ("the answer he was born to make", wrote Douglas Southall Freeman; another called it a "no-brainer") given the ties to family and state, an 1871 letter from his eldest daughter, Mary Custis Lee, to a biographer described Lee as "worn and harassed" yet calm as he deliberated alone in his office. People on the street noticed Lee's grim face as he tried to decide over the next two days, and he later said that he kept the resignation letter for a day before sending it on April 20. Two days later the Richmond convention invited Lee to the city. It elected him as commander of Virginia state forces before his arrival on April 23, and almost immediately gave him George Washington's sword as symbol of his appointment; whether he was told of a decision he did not want without time to decide, or did want the excitement and opportunity of command, is unclear.[11][104][102]

A cousin on Scott's staff told the family that Lee's decision so upset Scott that he collapsed on a sofa and mourned as if he had lost a son, and asked not to hear Lee's name. When Lee told family his decision, he said "I suppose you will all think I have done very wrong", as the others were mostly pro-Union; only Mary Custis was a secessionist, and her mother especially wanted to choose the Union, but told her husband that she would support whatever he decided. Many younger men like nephew Fitzhugh wanted to support the Confederacy, but Lee's three sons joined the Confederate military only after their father's decision.[104][102]

Most family members, like brother Smith, also reluctantly chose the South, but Smith's wife and Anne, Lee's sister, still supported the Union; Anne's son joined the Union Army, and no one in his family ever spoke to Lee again. Many cousins fought for the Confederacy, but Phillips and John Fitzgerald told Lee in person that they would uphold their oaths; John H. Upshur stayed with the Union military despite much family pressure; Roger Jones stayed in the Union army after Lee refused to advise him on what to do; and two of Philip Fendall's sons fought for the Union. Forty percent of Virginian officers stayed with the North.[104][102]

Early role

At the outbreak of war, Lee was appointed to command all of Virginia's forces, which then encompassed the Provisional Army of Virginia and the Virginia State Navy. He was appointed a Major General by the Virginia Governor, but upon the formation of the Confederate States Army, he was named one of its first five full generals. Lee did not wear the insignia of a Confederate general, but only the three stars of a Confederate colonel, equivalent to his last U.S. Army rank.[108] He did not intend to wear a general's insignia until the Civil War had been won and he could be promoted, in peacetime, to general in the Confederate Army.

Lee's first field assignment was commanding Confederate forces in western Virginia, where he was defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain and was widely blamed for Confederate setbacks.[109] He was then sent to organize the coastal defenses along the Carolina and Georgia seaboard, appointed commander, "Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida" on November 5, 1861. Between then and the fall of Fort Pulaski, April 11, 1862, he put in place a defense of Savannah that proved successful in blocking Federal advance on Savannah. Confederate fort and naval gunnery dictated nighttime movement and construction by the besiegers. Federal preparations required four months. In those four months, Lee developed a defense in depth. Behind Fort Pulaski on the Savannah River, Fort Jackson was improved, and two additional batteries covered river approaches.[110] In the face of the Union superiority in naval, artillery and infantry deployment, Lee was able to block any Federal advance on Savannah, and at the same time, well-trained Georgia troops were released in time to meet McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. The city of Savannah would not fall until Sherman's approach from the interior at the end of 1864.

At first, the press spoke to the disappointment of losing Fort Pulaski. Surprised by the effectiveness of large caliber Parrott Rifles in their first deployment, it was widely speculated that only betrayal could have brought overnight surrender to a Third System Fort. Lee was said to have failed to get effective support in the Savannah River from the three sidewheeler gunboats of the Georgia Navy. Although again blamed by the press for Confederate reverses, he was appointed military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, the former U.S. Secretary of War. While in Richmond, Lee was ridiculed as the 'King of Spades' for his excessive digging of trenches around the capitol. These trenches would later play a pivotal role in battles near the end of the war.[111]

Army of Northern Virginia commander (June 1862 – June 1863)

In the spring of 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, the Union Army of the Potomac under General George B. McClellan advanced on Richmond from Fort Monroe. Progressing up the Peninsula, McClellan forced Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and the Army of Virginia to retreat to a point just north and east of the Confederate capital.

Johnston was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, on June 1, 1862, giving Lee his first opportunity to lead an army in the field – the force he renamed the Army of Northern Virginia, signalling confidence that the Union army could be driven away from Richmond. Early in the war, Lee had been called "Granny Lee" for his allegedly timid style of command.[112] Confederate newspaper editorials objected to him replacing Johnston, opining that Lee would be passive, waiting for Union attack. This seemed true, initially; for the first three weeks of June, Lee did not show aggression, instead strengthening Richmond's defenses.

However, on June 25, he surprised the Army of the Potomac and launched a rapid series of bold attacks: the Seven Days Battles. Despite superior Union numbers and some clumsy tactical performances by his subordinates, Lee's attacks derailed McClellan's plans and drove back most of his forces. Confederate casualties were heavy, but an unnerved McClellan, famed for his caution, retreated 25 miles (40 km) to the lower James River, and abandoned the Peninsula completely in August. This success changed Confederate morale and the public's regard for Lee. After the Seven Days Battles, and until the end of the war, his men called him "Marse Robert", a term of respect and affection.[113]

The setback, and the resulting drop in Union morale, impelled Lincoln to adopt a new policy of relentless, committed warfare.[114][115] After the Seven Days, Lincoln decided he had to move to emancipate most Confederate slaves by executive order, as a military act, using his authority as commander-in-chief.[116] To make this possible, he needed a Union victory.

Wheeling to the north, Lee marched rapidly towards Washington, D.C. and defeated another Union army under Gen. John Pope at the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August. He eliminated Pope before reinforcements from McClellan arrived, knocking out an entire field command before another could arrive to support it. In less than 90 days, Lee had run McClellan off the Peninsula, defeated Pope, and moved the battle lines 82 miles (132 km) north, from 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Richmond to 20 miles (32 km) south of Washington.

Lee chose to take the battle off southern ground and invaded Maryland and Pennsylvania, hoping to collect supplies in Union territory, and possibly win a victory that would sway the upcoming Union elections in favor of ending the war. This was sent amiss when McClellan's men found a lost Confederate dispatch, Special Order 191, revealing Lee's plans and movements. McClellan always exaggerated Lee's numerical strength, but now he knew the Confederate army was divided and could be destroyed in detail. Still, in a characteristic manner, McClellan moved slowly; he failed to realize a spy had informed Lee that he possessed the plans. Lee quickly concentrated his forces west of Antietam Creek, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, where McClellan attacked on September 17. The Battle of Antietam was the single bloodiest day of the war, with both sides suffering enormous losses. Lee's army barely withstood the Union assaults, and retreated to Virginia the next day. The narrow Confederate defeat gave President Abraham Lincoln the opportunity to issue his Emancipation Proclamation,[117] which put the Confederacy on the diplomatic and moral defensive.[118]

Disappointed by McClellan's failure to destroy Lee's army, Lincoln named Ambrose Burnside the commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside ordered an attack across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Delays in bridging the river allowed Lee's army ample time to organize strong defenses, and the Union frontal assault on December 13, 1862, was a disaster. There were 12,600 Union casualties to 5,000 Confederate, making the engagement one of the most one-sided battles in the Civil War.[119] After this victory, Lee reportedly said, "It is well that war is so terrible, else we should grow too fond of it."[119] At Fredericksburg, according to historian Michael Fellman, Lee had completely entered into the "spirit of war, where destructiveness took on its own beauty".[119]

The bitter Union defeat at Fredericksburg prompted President Lincoln to appoint Joseph Hooker as the next commander of the Army of the Potomac. In May 1863, Hooker maneuvered to attack Lee's army by crossing the Rapahannock further upriver and positioning himself at the Chancellorsville crossroads. Doing this could give him an opportunity to strike Lee in the rear, but the Confederate General barely managed to pivot his forces in time to face an attack. Hooker's command was nearly twice the size of Lee's but he nonetheless was beaten after Lee performed a daring movement that broke all terms of conventional warfare: dividing his army. Lee sent Stonewall Jackson's corps to attack Hooker's exposed flank, on the opposite side of the battlefield. The significant victory that followed came with a price. Among the heavy casualties was Jackson, his finest corps commander, accidentally fired on by his own troops.[120]

Even though he scored another impressive victory over an enemy army much larger than his own, Lee felt unsatisfied by the fact that he had made little territorial gains up to that point. Things were going poorly for the Confederacy in the West, and Lee started to grow restless; he devised a plan to once again invade the North, for similar reasons to before: relieve Virginia and its citizens of the weariness of battle, and potentially march on the Federal Capital and force terms of peace.

Battle of Gettysburg

Critical decisions came in May–June 1863, after Lee's smashing victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville. The western front was crumbling, as multiple uncoordinated Confederate armies were unable to handle General Ulysses S. Grant's campaign against Vicksburg. The top military advisers wanted to save Vicksburg, but Lee persuaded Davis to overrule them and authorize yet another invasion of the North. The immediate goal was to acquire urgently needed supplies from the rich farming districts of Pennsylvania; a long-term goal was to stimulate peace activity in the North by demonstrating the power of the South to invade. Lee's decision proved a significant strategic blunder and cost the Confederacy control of its western regions, and nearly cost Lee his own army as Union forces cut him off from the South.[121]

Lee launched the Gettysburg Campaign when he abandoned his position on the Rapahannock and crossed the Potomac River into Maryland in June. Hooker mobilized his men and pursued, but was replaced by Gen. George G. Meade on June 28, a few days before the two armies clashed at the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in early July; the battle produced the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War. Some of Lee's subordinates were new and inexperienced to their commands, and J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry failed to perform effective reconnaissance. The first day was a surprise affair for both sides, and the Confederates managed to rally their forces first, pushing the panicked Union troops away from town, and towards key terrain that should have been taken by General Ewell, but was not. The second day unfolded differently for the Confederates. They took too much time to assemble, and launched repeated failed assaults against the Union left flank over difficult terrain. Lee's decision on the third day, going against the advice of his best corps commander, Gen. James Longstreet, to launch a massive frontal assault on the center of the Union line, was disastrous. It was carried out over a wide field, and has come to be known commonly as Pickett's Charge. Easily repulsed, Pickett's Charge, named after the general whose division participated, resulted in severe Confederate losses. Lee rode out to meet the remains of the division and proclaimed, "All this has been my fault."[122] He had no choice but to withdraw, and he escaped Meade's ineffective pursuit, slipping back into Virginia.

Following his defeat at Gettysburg, Lee sent a letter of resignation to President Davis on August 8, 1863, but Davis refused Lee's pleas to retire. That fall, Lee and Meade met again in two minor campaigns, Bristoe and Mine Run, that did little to change the strategic standoff. The Confederate Army never fully recovered from the substantial losses incurred during the three-day battle in southern Pennsylvania. Civil War Historian Shelby Foote once stated, "Gettysburg was the price the South paid for having Robert E. Lee as commander."[citation needed]

Ulysses S. Grant and the Union offensive

In 1864 the new Union general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, sought to use his large advantages in manpower and material resources to destroy Lee's army by attrition, pinning Lee against his capital of Richmond. Lee successfully stopped each attack, but Grant with his superior numbers kept pushing each time a bit farther to the southeast. These battles in the Overland Campaign included the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and Cold Harbor.

Grant eventually was able to stealthily move his army across the James River. After stopping a Union attempt to capture Petersburg, Virginia, a vital railroad link supplying Richmond, Lee's men built elaborate trenches and were besieged in Petersburg, a development which presaged the trench warfare of World War I. Lee attempted to break the stalemate by sending Jubal A. Early on a raid through the Shenandoah Valley to Washington, D.C., but Early was defeated early on by the superior forces of Philip Sheridan. The Siege of Petersburg lasted from June 1864 until March 1865, with Lee's outnumbered and poorly supplied army shrinking daily because of desertions by disheartened Confederates.

General in Chief

On February 6, 1865, Lee was appointed General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate States.

As the South ran out of manpower, the issue of arming the slaves became paramount. Lee explained, "We should employ them without delay ... [along with] gradual and general emancipation". The first units were in training as the war ended.[123][124] As the Confederate army was devastated by casualties, disease and desertion, the Union attack on Petersburg succeeded on April 2, 1865. Lee abandoned Richmond and retreated west. Lee then made an attempt to escape to the southwest and join up with Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee in North Carolina. However, his forces were soon surrounded and he surrendered them to Grant on April 9, 1865, at the Battle of Appomattox Court House.[125] Other Confederate armies followed suit and the war ended. The day after his surrender, Lee issued his Farewell Address to his army.

Lee resisted calls by some officers to reject surrender and allow small units to melt away into the mountains, setting up a lengthy guerrilla war. He insisted the war was over and energetically campaigned for inter-sectional reconciliation. "So far from engaging in a war to perpetuate slavery, I am rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe it will be greatly for the interests of the South."[126]

Summaries of Lee's Civil War battles

The following are summaries of Civil War campaigns and major battles where Robert E. Lee was the commanding officer:[127]

| Battle | Date | Result | Opponent | Confederate troop strength | Union troop strength | Confederate casualties | Union casualties | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheat Mountain | September 11–13, 1861 | Defeat | Reynolds | 5,000 | 3,000 | c. 90 | 88 | Lee's first battle of the Civil War. Severely criticized, Lee was nicknamed "Granny Lee". Lee was sent to South Carolina and Georgia to supervise fortifications.[128] |

| Seven Days | June 25 – July 1, 1862 | Tactically inconclusive; strategic Confederate victory

|

McClellan | 95,000 | 91,000 | 20,614 | 15,849 | Tactically inconclusive; strategic Confederate victory, as McClellan's retreat to Harrison's Landing ended the Peninsula Campaign.[129] Lee acquitted himself well, and remained in field command for the duration of the war under the direction of Jefferson Davis. Union troops remained on the Lower Peninsula and at Fortress Monroe. |

| Second Manassas | August 28–30, 1862 | Victory | Pope | 50,000 | 77,000 | 7,298 | 14,462 | Union forces continued to occupy parts of northern Virginia but were unable to expand further. |

| South Mountain | September 14, 1862 | Defeat | McClellan | 18,000 | 28,000 | 2,685 | 2,325 | Confederates lost control of westernmost Virginian congressional districts which would later be the core counties of West Virginia. |

| Antietam | September 16–18, 1862 | Inconclusive | McClellan | 52,000 | 75,000 | 13,724 | 12,410 | Tactically inconclusive but strategically a Union victory. The Confederates lost an opportunity to gain foreign recognition; Lincoln moved forward on his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. |

| Fredericksburg | December 11, 1862 | Victory | Burnside | 72,000 | 114,000 | 5,309 | 12,653 | With Lee's troops and supplies depleted, Confederates remained in place south of the Rappahannock. Union forces did not withdraw from northern Virginia. |

| Chancellorsville | May 1, 1863 | Victory | Hooker | 60,298 | 105,000 | 12,764 | 16,792 | Union forces withdrew to ring of defenses around Washington, D.C. |

| Gettysburg | July 1, 1863 | Defeat | Meade | 75,000 | 83,000 | 23,231–28,063 | 23,049 | The Confederate army was physically and spiritually exhausted. Meade was criticized for not immediately pursuing Lee's army. This battle become known as the high water mark of the Confederacy.[130] Lee never again led an invasion of the North after this battle. Rather he was determined to defend Richmond and eventually Petersburg at all costs. |

| Wilderness | May 5, 1864 | Inconclusive | Grant | 61,000 | 102,000 | 11,033 | 17,666 | Grant disengaged and continued his offensive, circling east and south advancing on Richmond and Petersburg. |

| Spotsylvania | May 12, 1864 | Inconclusive[131] | Grant | 52,000 | 100,000 | 12,687 | 18,399 | Although beaten and unable to take Lee's defenses, Grant continued the Union offensive, circling east and south and advancing on Richmond and Petersburg |

| North Anna | May 23–26, 1864 | Inconclusive | Grant | 50,000–53,000 | 67,000–100,000 | 1,552 | 3,986 | North Anna proved to be a relatively minor affair when compared to other Civil War battles. |

| Totopotomoy Creek | May 28–30, 1864 | Inconclusive | Grant | N/A | N/A | 1,593 | 731 | Grant continued his attempts to maneuver around Lee's right flank and lure him into a general battle in the open. |

| Cold Harbor | June 1, 1864 | Victory | Grant | 62,000 | 108,000 | 5,287 | 12,000 | Although Grant was able to continue his offensive, Grant referred to the Cold Harbor assault as his "greatest regret" of the war in his memoirs. |

| Fussell's Mill | August 14, 1864 | Inconclusive | Hancock | 20,000 | 28,000 | 1,700 | 2,901 | Union attempt to break Confederate siege lines at Richmond, the Confederate capital. |

| Appomattox Campaign | March 29, 1865 | Defeat | Grant | 56,000 | 114,000 | c. 25,000 General Lee surrenders | c. 9,700 | General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant.[132] After the surrender Grant gave Lee's army much-needed food rations; they were paroled to return to their homes, never again to take up arms against the Union. |

Postbellum life

| External videos | |

|---|---|

After the war, Lee was not arrested or punished (although he was indicted),[133] but he did lose the right to vote as well as some property. Lee's prewar family home, the Custis-Lee Mansion, was seized by Union forces during the war and turned into Arlington National Cemetery, and his family was not compensated until more than a decade after his death.[134]

In 1866, Lee counseled Southerners not to resume fighting, which prompted Grant to say that Lee was "setting an example of forced acquiescence so grudging and pernicious in its effects as to be hardly realized".[135] Lee joined with Democrats in opposing the Radical Republicans, who demanded punitive measures against the South, distrusted the South's commitment to the abolition of slavery, and, indeed, distrusted the region's loyalty to the United States.[136][137] Lee supported a system of free public schools for black people but opposed allowing them to vote: "My own opinion is that, at this time, they [black Southerners] cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the [vote] would lead to a great deal of demagogism, and lead to embarrassments in various ways."[138] Emory Thomas says Lee had become a suffering Christ-like icon for ex-Confederates. President Grant invited him to the White House in 1869, and he went. Nationally, Lee became an icon of reconciliation between the white people of the North and South, and the reintegration of former Confederates into the national fabric.[139]

Lee hoped to retire to a farm of his own, but he was too much a regional symbol to live in obscurity. From April to June 1865, he and his family resided in Richmond at the Stewart-Lee House.[140] He accepted an offer to serve as the president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, and served from October 1865 until his death. The trustees used his famous name in large-scale fund-raising appeals and Lee transformed Washington College into a leading Southern college, expanding its offerings significantly, adding programs in commerce and journalism, and incorporating the Lexington Law School. Lee was well liked by the students, which enabled him to announce an "honor system" like that of West Point, explaining that "we have but one rule here, and it is that every student be a gentleman". To speed up national reconciliation, Lee recruited students from the North and made certain they were well treated on campus and in town.[141]

Several glowing appraisals of Lee's tenure as college president have survived, depicting the dignity and respect he commanded among all. Previously, most students had been obliged to occupy the campus dormitories, while only the most mature were allowed to live off-campus. Lee quickly reversed this rule, requiring most students to board off-campus, and allowing only the most mature to live in the dorms as a mark of privilege; the results of this policy were considered a success. A typical account by a professor there states that "the students fairly worshipped him, and deeply dreaded his displeasure; yet so kind, affable, and gentle was he toward them that all loved to approach him. ... No student would have dared to violate General Lee's expressed wish or appeal."[142]

While at Washington College, Lee told a colleague that the greatest mistake of his life was taking a military education.[143] He also defended his father in a biographical sketch.[144]

President Johnson's amnesty pardons

On May 29, 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued a Proclamation of Amnesty and Pardon to persons who had participated in the rebellion against the United States. There were fourteen excepted classes, though, and members of those classes had to make special application to the president. Lee sent an application to Grant and wrote to President Johnson on June 13, 1865:

Being excluded from the provisions of amnesty & pardon contained in the proclamation of the 29th Ulto; I hereby apply for the benefits, & full restoration of all rights & privileges extended to those included in its terms. I graduated at the Mil. Academy at West Point in June 1829. Resigned from the U.S. Army April '61. Was a General in the Confederate Army, & included in the surrender of the Army of N. Virginia 9 April '65.[145]

On October 2, 1865, the same day that Lee was inaugurated as president of Washington College, he signed his Amnesty Oath, thereby complying fully with the provision of Johnson's proclamation. Lee was not pardoned, nor was his citizenship restored.[145]

Three years later, on December 25, 1868, Johnson proclaimed a second amnesty which removed previous exceptions, such as the one that affected Lee.[146]

Postwar politics

Lee, who had opposed secession and remained mostly indifferent to politics before the Civil War, supported President Andrew Johnson's plan of Presidential Reconstruction that took effect in 1865–66. However, he opposed the Congressional Republican program that took effect in 1867. In February 1866, he was called to testify before the Joint Congressional Committee on Reconstruction in Washington, where he expressed support for Johnson's plans for quick restoration of the former Confederate states, and argued that restoration should return, as far as possible, to the status quo ante in the Southern states' governments (with the exception of slavery).[147]

Lee told the committee that "every one with whom I associate expresses kind feelings towards the freedmen. They wish to see them get on in the world, and particularly to take up some occupation for a living, and to turn their hands to some work." and that "Where I am, and have been, the people have exhibited a willingness that the blacks should be educated, and ... that it would be better for the blacks and for the whites". However, when he was asked "General, you are very competent to judge of the capacity of black men for acquiring knowledge: I want your opinion on that capacity, as compared with the capacity of white men?" Lee replied "I do not think that he is as capable of acquiring knowledge as the white man is." Lee forthrightly opposed allowing blacks to vote: "My own opinion is that, at this time, they [black Southerners] cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the [vote] would lead to a great deal of demagogism, and lead to embarrassments in various ways."[148][149]

In an interview in May 1866, Lee said: "The Radical party are likely to do a great deal of harm, for we wish now for good feeling to grow up between North and South, and the President, Mr. Johnson, has been doing much to strengthen the feeling in favor of the Union among us. The relations between the Negroes and the whites were friendly formerly, and would remain so if legislation be not passed in favor of the blacks, in a way that will only do them harm."[150]

In 1868, Lee's ally Alexander H. H. Stuart drafted a public letter of endorsement for the Democratic Party's presidential campaign, in which Horatio Seymour ran against Lee's old foe Republican Grant. Lee signed it along with thirty-one other ex-Confederates. The Democratic campaign, eager to publicize the endorsement, published the statement widely in newspapers.[151] Their letter claimed paternalistic concern for the welfare of freed Southern blacks, stating that "The idea that the Southern people are hostile to the negroes and would oppress them, if it were in their power to do so, is entirely unfounded. They have grown up in our midst, and we have been accustomed from childhood to look upon them with kindness."[152] However, it also called for the restoration of white political rule, arguing that "It is true that the people of the South, in common with a large majority of the people of the North and West, are, for obvious reasons, inflexibly opposed to any system of laws that would place the political power of the country in the hands of the negro race. But this opposition springs from no feeling of enmity, but from a deep-seated conviction that, at present, the negroes have neither the intelligence nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe depositories of political power."[153]

In his public statements and private correspondence, Lee argued that a tone of reconciliation and patience would further the interests of white Southerners better than hotheaded antagonism to federal authority or the use of violence. Lee repeatedly expelled white students from Washington College for violent attacks on local black men, and publicly urged obedience to the authorities and respect for law and order.[154] He privately chastised fellow ex-Confederates such as Davis and Jubal Early for their frequent, angry responses to perceived Northern insults, writing in private to them as he had written to a magazine editor in 1865, that "It should be the object of all to avoid controversy, to allay passion, give full scope to reason and to every kindly feeling. By doing this and encouraging our citizens to engage in the duties of life with all their heart and mind, with a determination not to be turned aside by thoughts of the past and fears of the future, our country will not only be restored in material prosperity, but will be advanced in science, in virtue and in religion."[155]

Illness and death

On September 28, 1870, Lee suffered a stroke. Two weeks later, shortly after 9 a.m. on October 12, 1870, Lee died in Lexington, Virginia, from pneumonia. According to one account, Lee's last words the day of his death were, "Tell Hill he must come up! Strike the tent",[156] but this is not fully confirmed because there are conflicting accounts and because Lee's stroke had resulted in aphasia, possibly rendering him unable to speak.[157]

At first no suitable coffin for the body could be located. The muddy roads were too flooded for anyone to get in or out of the town of Lexington. An undertaker had ordered three from Richmond that had reached Lexington, but due to unprecedented flooding from long-continued heavy rains, the caskets were washed down the Maury River. Two neighborhood boys, C.G. Chittum and Robert E. Hillis, found one of the coffins that had been swept ashore. Undamaged, it was used for the body, though it was a bit short for him. As a result, Lee was buried without shoes.[158] He was buried underneath the college chapel now known as University Chapel at Washington and Lee University, where his body remains.[32][159]

Legacy

Among the supporters of the Confederacy, Lee came to be even more revered after his surrender than he had been during the war, when Stonewall Jackson had been the great Confederate hero. In an 1874 address before the Southern Historical Society in Atlanta, Georgia, Benjamin Harvey Hill described Lee in this way:

He was a foe without hate; a friend without treachery; a soldier without cruelty; a victor without oppression, and a victim without murmuring. He was a public officer without vices; a private citizen without wrong; a neighbour without reproach; a Christian without hypocrisy, and a man without guile. He was a Caesar, without his ambition; Frederick, without his tyranny; Napoleon, without his selfishness, and Washington, without his reward.[160]

By the end of the 19th century, Lee's popularity had spread to the North.[161] Lee's admirers have pointed to his character and devotion to duty, and his occasional tactical successes in battles against a stronger foe.

According to my notion of military history there is as much instruction both in strategy and in tactics to be gleaned from General Lee's operations of 1862 as there is to be found in Napoleon's campaigns of 1796.

— Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley[162]

Military historians continue to pay attention to his battlefield tactics and maneuvering, though many think he should have designed better strategic plans for the Confederacy. He was not given full direction of the Southern war effort until late in the conflict.

Historian Eric Foner writes that at the end of his life

Lee had become the embodiment of the Southern cause. A generation later, he was a national hero. The 1890s and early 20th century witnessed the consolidation of white supremacy in the post-Reconstruction South and widespread acceptance in the North of Southern racial attitudes.[88]

Robert E. Lee has been commemorated on U.S. postage stamps at least five times, the first one being a commemorative stamp that also honored Stonewall Jackson, issued in 1936. A second "regular-issue" stamp was issued in 1955. He was commemorated with a 32-cent stamp issued in the American Civil War Issue of June 29, 1995. His horse Traveller is pictured in the background.[163]

Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia was commemorated on its 200th anniversary on November 23, 1948, with a three-cent postage stamp. The central design is a view of the university, flanked by portraits of generals George Washington and Robert E. Lee.[164] Lee was again commemorated on a commemorative stamp in 1970, along with Jefferson Davis and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, depicted on horseback on the six-cent Stone Mountain Memorial commemorative issue, modeled after the actual Stone Mountain Memorial carving in Georgia. The stamp was issued on September 19, 1970, in conjunction with the dedication of the Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial in Georgia on May 9, 1970. The design of the stamp replicates the memorial, the largest high relief sculpture in the world. It is carved on the side of Stone Mountain 400 feet above the ground.[165]

Stone Mountain also led to Lee's appearance on a commemorative coin, the 1925 Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar. During the 1920s and '30s dozens of specially designed half dollars were struck to raise money for various events and causes. This issue had a particularly wide distribution, with 1,314,709 minted. Unlike some of the other issues it remains a very common coin.

In 1865, after the war, Lee was paroled and signed an oath of allegiance, asking to have his citizenship of the United States restored. However, his application was not processed by Secretary of State William Seward, and as a result Lee did not receive a pardon and his citizenship was not restored.[166][167] On January 30, 1975, Senate Joint Resolution 23, "A joint resolution to restore posthumously full rights of citizenship to General R. E. Lee" was introduced into the Senate by Senator Harry F. Byrd Jr. (I-VA), the result of a five-year campaign to accomplish this. Proponents portrayed the lack of pardon as a mere clerical error. The resolution, which enacted Public Law 94–67, was passed, and the bill was signed by President Gerald Ford on August 5.[168][169][170]

World War II general George S. Patton said he had prayed to a portrait of General Lee, as well as one of Stonewall Jackson, as a young child, believing them to be portraits of God and Jesus, and associating their features with his perceptions of the two men.[171]

Monuments, memorials and commemorations

Lee opposed the construction of public memorials to Confederate rebellion on the grounds that they would prevent the healing of wounds inflicted during the war.[172] Nevertheless, after his death, he became an icon used by promoters of "Lost Cause" mythology, who sought to romanticize the Confederate cause and strengthen white supremacy in the South.[172] Later in the 20th century, particularly following the civil rights movement, historians reassessed Lee; his reputation fell based on his failure to support rights for freedmen after the war, and even his strategic choices as a military leader fell under scrutiny.[88][173]

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, also known as the Custis–Lee Mansion,[174] is a Greek revival mansion in Arlington, Virginia, that was once Lee's home. It overlooks the Potomac River and the National Mall in Washington, D.C. During the Civil War, the grounds of the mansion were selected as the site of Arlington National Cemetery, in part to ensure that Lee would never again be able to return to his home. The United States designated the mansion as a National Memorial to Lee in 1955, a mark of widespread respect for him in both the North and South.[175]

In Richmond, Virginia, a large equestrian statue of Lee by French sculptor Jean Antonin Mercié was the centerpiece of Monument Avenue, along with four other statues of Confederates. This monument to Lee was unveiled on May 29, 1890; over 100,000 people attended this dedication. That has been described as "the day white Virginia stopped admiring Gen. Robert E. Lee and started worshiping him".[176] The four other Confederate statues were removed in 2020, and the equestrian statue of Lee was removed on September 8, 2021, at the direction of the state government.[177]

Lee is also shown mounted on Traveller in Gettysburg National Military Park on top of the Virginia Monument; he is facing roughly in the direction of Pickett's Charge. Lee's portrayal on a mural on Richmond's flood wall on the James River, considered offensive by some, was removed in the late 1990s, but currently is back on the flood wall.