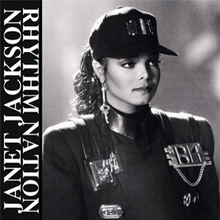

Rhythm Nation

| "Rhythm Nation" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Janet Jackson | ||||

| from the album Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814 | ||||

| Released | October 23, 1989[1] | |||

| Recorded | January 1989[2] | |||

| Studio | Flyte Tyme (Minneapolis, Minnesota)[3] | |||

| Genre | Dance | |||

| Length | 5:31 | |||

| Label | A&M | |||

| Songwriter(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Janet Jackson singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Rhythm Nation" on YouTube | ||||

"Rhythm Nation" is a song by American singer Janet Jackson, released as the second single from her fourth studio album, Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814 (1989). It was written and produced by Jackson, in collaboration with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. Jackson developed the song's concept in response to various tragedies in the media, deciding to pursue a socially conscious theme by using a political standpoint within upbeat dance music. In the United States, it peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 and topped the Hot Black Singles and Dance Club Songs charts. It also peaked within the top 40 of several singles charts worldwide. "Rhythm Nation" received several accolades, including BMI Pop Awards for "Most Played Song", the Billboard Award for "Top Dance/Club Play Single" and a Grammy nomination for Jackson as "Producer of the Year". It has been included in two of Jackson's greatest hits collections, Design of a Decade: 1986–1996 (1995) and Number Ones (2009).

The music video for "Rhythm Nation" was directed by Dominic Sena and choreographed by Jackson and a then-unknown Anthony Thomas. It served as the final segment in Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814 film. It portrays rapid choreography within a "post-apocalyptic" warehouse setting, with Jackson and her dancers adorned in unisex military attire. It was filmed in black-and-white to portray the song's theme of racial harmony. Jackson's record label attempted to persuade her against filming the video, but upon her insistence it became "the most far-reaching single project the company has ever attempted." The video received two MTV Video Music Awards for "Best Choreography" and "Best Dance Video." Jackson also won the Billboard Award for "Best Female Video Artist" in addition to the "Director's Award" and "Music Video Award for Artistic Achievement." The Rhythm Nation 1814 film won the Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video. The video's outfit was inducted into the National Museum of Women in the Arts and Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, where its hand-written lyrics are also used in the museum's class on female songwriters.

Artists such as Sleigh Bells, Jamie Lidell, and Kylie Minogue have cited the song as an influence, while artists including Lady Gaga, Peter Andre, OK Go, Mickey Avalon, Usher, Keri Hilson, and Britney Spears have referenced its music video. Beyoncé, Cheryl Cole, Rihanna and Ciara have also paid homage to its outfit and choreography within live performances. It has inspired the careers of choreographers such as Darrin Henson and Travis Payne. Actors including Kate Hudson, Michael K. Williams, and Elizabeth Mathis have studied its music video, with its choreography also used in the film Tron: Legacy. It has been covered by Pink, Crystal Kay, and Girls' Generation and has also been performed on Glee, The X Factor USA, and Britain's Got Talent.

Background

[edit]Upon recording her fourth studio album, Jackson was inspired to cover socially conscious issues as a response to various tragedies in the media.[4] Producer Jimmy Jam stated, "Janet came up with the 'Rhythm Nation' concept. A lot of it had to do with watching TV. We're avid TV watchers, and we would watch MTV, then switch over to CNN, and there'd always be something messed-up happening. It was never good news, always bad news."[4] She was particularly saddened by the Stockton playground murders, leading her to record "Livin' in a World (They Didn't Make)." She decided to pursue additional songs with a similar concept, focusing on a political standpoint within energetic dance music.[4] The song's lyrics were written as a montage of racial unity with Jackson's passion for dance, envisioning a colorblind world sharing the same beliefs.[5] Jam explained:

We wanted something to do with rhythm, because that's what Janet's life is about: beat, rhythm. One night over dinner, Janet said, "rhythm nation." I told Terry, and he just sang the melody, "We are part of the rhythm nation." And then I hit, "The people of the world today, searching for a better way of life", and Janet sings, "Rhythm Nation." And it just all came together.[6]

We have so little time to solve these problems. I want people to realize the urgency. I want to grab their attention. Music is my way of doing that. It's okay to have fun — I want to be certain that point is clear. I have fun. Dancing is fun. Dancing is healthy. It pleases me when the kids say my stuff is kickin', but it pleases me even more when they listen to the lyrics. The lyrics mean so much to me.

— Jackson on the concept of "Rhythm Nation."[7]

Jackson jokingly considered it a "national anthem for the Nineties", leading her to develop Rhythm Nation 1814, titled after the year "The Star-Spangled Banner" was written.[8] She derived its lyrical theme from the diversity amongst society, which she observed to be united by music. Jackson said, "I realized that among my friends, we actually had a distinct 'nation' of our own. We weren't interested in drugs or drinking but social change. We also loved music and loved to dance... that's how Rhythm Nation 1814 was born."[9] She also likened its concept to the various groups formed among youth, asserting a common identity and bond, saying, "I thought it would be great if we could create our own nation. One that would have a positive message and that everyone would be free to join."[10] Jackson also commented, "I found it so intriguing that everyone united through whatever the link was. And I felt that with most of my friends. Most people think that my closest friends are in the [entertainment] business, and they're not. They're roller-skating rink guards, waitresses, one works for a messenger service. They have minimum-wage paying jobs. And the one thing that we all have in common is music. I know that within our little group, there is a rhythm nation that exists."[8]

Jackson desired the song's theme to capture the attention of her teenage audience, who were potentially unaware of socially conscious themes. She commented, "I wanted to take our message directly to the kids, and the way to do that is by making music you can really dance to. That was our whole goal: How can I get through to the kids with this?"[10] She became encouraged by artists such as Marvin Gaye, Bob Dylan, and Joni Mitchell, feeling as if their demographics were already familiar with social themes.[9] Jackson said, "These were people who woke me up to the responsibility of music. They were beautiful singers and writers who felt for others. They understood suffering."[9] Upon questioning, Jackson said, "I know I can't change the world single-handedly, but for those who are on the fence, maybe I can lead them in a positive direction... If I just touched one person, just to make that difference, make them change for the better, that's an accomplishment."[8] Jackson also responded to potential ridicule, stating, "a lot of people have said, "She's not being realistic with this Rhythm Nation. It's like 'Oh, she thinks the world is going to come together through her dance music,' and that's not the case at all. I know a song or an album can't change the world. But there's nothing wrong with doing what we're doing to help spread the message."[11] Jackson added, "If personal freedom has political implications and if pleasure must be part of any meaningful solution—and it really must—there's nothing wrong with it at all."[11]

Composition

[edit]The distinctive guitar riff was based on "Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again)" by Sly and the Family Stone.[12] Its socially conscious lyrics preach racial harmony and leadership through dance, anti-fascism, protesting bigotry, and geographic boundaries with "compassionate, dedicated people power."[13][14] It uses a moderate funk tempo composed in the key of E minor. Jackson's vocals range from C4 to A5, climaxing during the song's middle eight.[15] It opens with prelude "Pledge", in which Jackson describes "a world rid of color-lines" over apocalyptic bells and ambient noise.[14] According to The New York Times' writer Stephen Holden, the song is an "utopian dance-floor exhortation" whose lyrics "[call] for racial harmony and cooperative struggle to create a better, stronger world".[16] Its chorus is supported by male voices, with Jackson addressing her audience in a similar vein to a politician, "abandoning the narrow I for the universal we and inviting us to do the same."[14] Its final chorus closes with multiple ad-libs as Jackson encourages listeners to sing with her, spreading the song's message of multicultural solidarity in a "grand pop statement."[14][17]

Critical reception

[edit]"Rhythm Nation" received positive reviews from critics, garnering praise for its lyrical theme. Rolling Stone declared it the album's "essential moment", describing the song as "a headbanging good time."[18] Stephen Holden of The New York Times called it a "militantly utopian dance-floor exhortation."[16] Michael Saunders of The Sun Sentinel declared it "upbeat funk-pop" which showcased Jackson's "light, breathy voice."[19]

Sputnik Music applauded its "extraordinary" production and chorus, thought to result in "a catchy, smart single which would appease the Jackson haters and delight the fans."[20] People specified its "burnin' hunk o' funk guitar riff".[21] Entertainment Weekly declared it a "paean to the human spirit", likened to "a chorus line of stormtroopers."[22] Vince Aletti of Rolling Stone described the song as a "densely textured, agitated track" propelled by "syncopated yelps" of unity.[14]

Theme reception

[edit]Vince Aletti considered its message "dedicated" and "compassionate", praising its concept of a "multiracial, multinational network." He added, "Jackson addresses her constituency the way a politician might, abandoning the narrow I for the universal we and inviting us to do the same."[14] Sal Cinquemani of Slant Magazine described it as a "socially charged calls to arms", promoting a "Zen-like transcendence of self." Its lyrics were regarded to call for "social justice" rather than personal freedom, focusing on "strength in numbers" and "unity through mandatory multiculturalism."[23] In May 2016, Entertainment Weekly ranked "Rhythm Nation" as the best Janet Jackson song of all time, commenting, "it rode to the new jack swing of its era, but this industrial-edged anthem ... is one of the most radical hits ever by a pop diva. It broke all of the lines, color and otherwise, high-stepping all the way.[24] Richard Croft called it "a protest song with a twist", commending its description of how change can be made rather than questioning why it hasn't occurred.[25] Women, Politics, and Popular Culture author Lilly Goren considered it to reflect "politically driven feminist messages."[26] Chris Willman of Los Angeles Times proposed its theme "big on community, stressing social consciousness for a young target audience and proposing a prejudice-free" nation.[27] An additional review stated, "[Janet] wanted social justice and voiced it in one of the most fabulous, bad ass ways possible."[28]

Jon Pareles of The New York Times praised its "earnest concern", also noting its "call for unity and good intentions." Its preach of racial unity was applauded, thought to unite "Ms. Jackson's opposition to racism with an image of a mass audience."[29][30] The publication also observed Jackson to eagerly "rail against societal ills like racism and domestic abuse."[31] Additionally, it was used as an example of a socially conscious song having influence over the public, thought to effectively call for "racial harmony and cooperative struggle to create a better, stronger world."[16] Pareles added Jackson "kept the propulsive funk and added worthy, generalized social messages".[32] An anecdote likened its theme of peace to the teachings of social activist Mahatma Gandhi, saying, ""Rhythm Nation" sheds light on the problem of apathy, which is common among young people today." Jackson's conscious lyrics and desire to "not only entertain, but to educate" was praised, concluding, "["Rhythm Nation"] speaks particularly to young people and encourages them to be the leaders of tomorrow."[33]

Commercial performance

[edit]"Rhythm Nation" debuted at number 49 on the Billboard Hot 100 for the week of November 11, 1989.[34] It was the week's highest new entry, breaking Madonna's consecutive streak of Hot Shot Debuts on the chart.[35] The song peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 on January 6, 1990, for two consecutive weeks.[34][35] It also reached number two on the Mainstream Top 40 chart and reached number one on the ATV Top 40 in addition to the Hot Black Singles and Hot Dance Club Play charts, topping the former chart for a single week (January 13, 1990), and the latter chart for three weeks.[35] "Rhythm Nation" was certified Gold by the Recording Industry of America (RIAA) on January 16, 1990.[36] Internationally, the single reached number two in Canada, number nine in the Netherlands, number 17 in New Zealand, number 19 in Ireland, number 22 in Switzerland, number 23 in the United Kingdom, and number 56 in Australia.[37][38][39][40][41]

Music video

[edit]

The music video for "Rhythm Nation" was directed by Dominic Sena. It was the final inclusion in Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814 film, following "Miss You Much" and "The Knowledge." Its premise focuses on rapid choreography within a "post-apocalyptic" warehouse setting, with Jackson and her dancers outfitted in unisex black military-style uniforms. It was filmed in black-and-white to portray the song's theme of racial harmony. Jackson stated, "There were so many races in that video, from Black to White and all the shades of gray in between. Black-and-white photography shows all those shades, and that's why we used it."[5] Its wardrobe also reflects the song's theme of gender equality, using matching unisex outfits.[5] Jackson commented, "The foggy, smoky street and the dark, black-and-white tone, that was all intentional. When you've done a lot of videos, it can be difficult to keep it fresh and new. You have to try something you've never done, in fear of looking like something you've already created."[42]

While developing its concept, Jackson's record label attempted to persuade her against filming the video, feeling as if it didn't have mainstream appeal. Upon her insistence, it became "the most far-reaching single project the company has ever attempted."[5] The video received multiple accolades, including MTV Video Music Awards for "Best Choreography" and "Best Dance Video." Jackson was also the recipient of the "Director's Award", "Best Female Video Artist", and the "Music Video Award for Artistic Achievement" at the Billboard Awards.[43][44] The film won a Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video.[45] It was later listed among the "Greatest Music Videos of All Time" by Slant Magazine.[46] Entertainment Weekly considered it "legendary" while Rolling Stone declared it "the gold standard for dystopian dance-pop music videos", thought to include "the most memorable choreography in pop video history."[47][48] MTV News commended it as "the clip that sent Jackson into the stratosphere as an envelope-pushing pop star."[49] The video's outfit is included in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame's "Women Who Rock: Vision, Passion, Power" exhibit and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and was previously displayed on a statue at Walt Disney World theme park

Live performances

[edit]

During its initial promotion, "Rhythm Nation" was performed on Top of the Pops and TV Plus, in addition to Germany's Countdown and Peter's Pop Show.[50][51] It was also performed for Queen Elizabeth II and the Royal Family at a Royal Variety Performance.[52] Jackson's pants split during the performance due to its intense choreography.[53] It was performed on The Ellen DeGeneres Show and America United: In Support of Our Troops concert during promotion for her tenth album, Discipline.[54][55] The song was notoriously performed with "All for You" and an excerpt of "The Knowledge" at the Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show, in which Jackson's breast was accidentally exposed by Justin Timberlake.[56] The performance led to the inspiration for YouTube and launch of Facebook, also becoming the most watched, recorded, and replayed event in television history.[57][58] It also set a record for Jackson as the most searched term and image in internet history.[58]

"Rhythm Nation" has been performed on all of her following tours. On the Rhythm Nation Tour, Jackson's performance was described as "a wedge of hard-driving bodies moves like a robot battalion in precision drill."[59] Jackson's outfit had been "mimicked by many of her fans" throughout the tour.[60] Observing its routine, The New York Times stated, "Legs chop wide open, then close again. They shoot out abruptly to the sides, then kick into jazz spins and bouncing splits to the floor. There are sedate pelvic jerks and a swiveling turn on a toe, trotting runs and purposeful syncopated walks. But essentially these are bodies rooted into the floor, taut yet alive in the way of a boxer edgily biding his time in the ring."[61] A live rendition from the janet. World Tour was aired on MTV.

The Velvet Rope Tour was reported to feature "the characteristic, Russian-style military suit she wore in the video, corresponding with the song's rigid, robotic dance movements." Los Angeles Times regarded her "a human musical medley", while The Daily Telegraph considered it "show-stopping" for its display of "hyperbolic tension."[62][63] Jackson's rendition on the All for You Tour was described as a "neon-lit number straight out of Blade Runner." Rolling Stone declared it "stunning", adding, "even near the end of the two-hour show, her voice was unwaveringly powerful, carrying the "Sing it people/Sing it children" lines like a flag on the Fourth of July."[64][65] Jackson's dancers emulated "animated toys and storybook figures" in catsuits, performing robotic moves against "structured, sassy beats."[66][67] On Number Ones, Up Close and Personal, Jackson's rendition was also praised, as she "sliced her way through tight, sharp choreography."[68] Alexis Petridis of The Guardian called it "ferocious", adding, "if she wanted to remind people how commanding a presence she can be, she's done her job."[69] Jackson also included the song on her 2015–16 Unbreakable World Tour; Jon Pareles of The New York Times, wrote that "as the concert neared its end, Ms. Jackson moved from the personal to the communal, summoning the staccato funk and calls for collective action of 'Rhythm Nation'. Suddenly, the number of onstage dancers more than doubled, all moving in sync".[70] She also has included the song on her current 2017–2019 State of the World Tour and her 2019 Las Vegas Residency Janet Jackson: Metamorphosis. It was also included on her special concert series Janet Jackson: A Special 30th Anniversary Celebration of Rhythm Nation in 2019.

Influence

[edit]"Rhythm Nation" has been cited to influence various artists within its production, lyrical theme and vocal arrangement. Its music video has also been considered among the most influential in popular culture. Rolling Stone observed it to "set the template for hundreds of videos to come in the Nineties and aughts", with Entertainment Weekly also declaring it "groundbreaking", in addition to "striking, timeless and instantly recognizable."[71][72] Mike Weaver stated Jackson's "one-of-a-kind, funk-and-groove choreography was unlike anything seen in the history of pop music. ... every show choir and every hiphop dancer wanted to cut and paste parts and pieces of the Rhythm Nation production into their set."[73] Regarding its influence, Sherri Winston of The Sun Sentinel stated, "No one can witness the militaristic precision of Rhythm Nation, which gives the impression that a really angry pep squad has taken over the dance floor, and not see how Janet's style has been sampled, borrowed and stolen over and over ... and over."[74]

The song has inspired artists such as Sleigh Bells,[75] Jamie Lidell,[76] Kylie Minogue,[77] and record producer Yoo Young-jin.[78] Various aspects of its music video have been referenced by numerous artists, including Britney Spears,[79] Justin Timberlake[80] Lady Gaga,[81] Peter Andre,[82] OK Go,[83] Nicki Minaj,[84] Usher,[85] and Jessie Ware.[86] Its outfit and choreography has been paid homage to in performances by Spears,[87] Beyoncé,[88] Cheryl Cole,[89] and Rihanna.[90] In film, actors such as Kate Hudson,[91] Michael K. Williams,[92] and Elizabeth Mathis have studied its music video, with Mathis notably using its choreography during a scene in Tron: Legacy.[93] Choreographers such as Travis Payne[94] and Wade Robson[95][96] have called it a primary influence to their careers. Aylin Zatar of BuzzFeed remarked, "She also basically pioneered the dancing in a warehouse, post-apocalyptic, industrial setting video. So, Britney ("Till The World Ends"), Rihanna ("Hard"), Lady Gaga ("Alejandro"), and even the Spice Girls ("Spice Up Your Life") – you all have Ms. Jackson to thank."[79]

Covers

[edit]Jacob Artist, Melissa Benoist, and Erinn Westbrook covered "Rhythm Nation" in a mashup with "Nasty" during the fifth season of Glee, in the episode "Puppet Master."[47][97] Pink covered "Rhythm Nation" for both the opening medley and in the finale medley with Queen and David Bowie's "Under Pressure" for the film Happy Feet Two. Japanese singer Crystal Kay performed a Japanese rendition of the song for the Japanese version of the film.[98] Girls' Generation performed the song on KBS Gayo Daechukje and their debut concert tour, Girls' Generation Asia Tour Into the New World.[99] Korean pop group After School covered the song on music show Kim Jung-eun's Chocolate.[100] American electronic musician Oneohtrix Point Never composed a cover of the song with choral arrangements by Thomas Roussel for Kenzo's Fall/Winter 2016 collection at Paris Fashion Week.[101]

The Stereo Hogzz performed a live rendition and replicated its choreography during the first season of The X Factor.[102] English dance troupe Diversity incorporated its choreography during a performance on the third season finale of Britain's Got Talent.[103] It was also performed on America's Best Dance Crew and Britain's Stars in Their Eyes.[104][105] Pink, Usher, and Mýa performed a dance tribute to "Rhythm Nation" on Jackson's MTV Icon special. Filipino singer Jaya included a live cover on the album Jaya Live at the Araneta.[106] The song's countdown is used in various releases of the video game NBA Live.

Awards and accolades

[edit]"Rhythm Nation" won a Billboard Award for "Top Dance/Club Play Single of the Year", with Jackson also winning "Best Female Artist, Dance", "Best Female Video Artist", "Director's Award", and the "Music Video Award for Artistic Achievement." The song also won a BMI Pop Award for "Most Played Song", in addition to awarding her "Songwriter of the Year." Jackson received a Grammy Award nomination for "Producer of the Year, Non-Classical", with its full-length music video winning "Best Long Form Music Video." Slant Magazine included it among the "Greatest Dance Songs of All Time" and "Greatest music Videos of All Time." VH1 ranked its music video among their "Greatest Videos." The video also won two MTV Video Music Awards for "Best Choreography" and "Best Dance Video", with Jackson awarded the Video Vanguard Award for her contributions to popular culture. The song is performed at Las Vegas' Legends in Concert series. The hand-written lyrics to "Rhythm Nation" and the music video's outfit are included in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's "Women Who Rock: Vision, Passion, Power" exhibit, with its lyrics also used in the museum's course on feminist songwriters. In 2021, it was listed at No. 475 on Rolling Stone's "Top 500 Best Songs of All Time".[107]

| List of accolades for "Rhythm Nation" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Legacy

[edit]The song exhorts social change in the face of injustice, using music – and by extension, rhythm – as a unifying tool. It's the perfect platform to talk about song structure (verse, chorus, bridge, etc.) More important, "Rhythm Nation" provides a unique point of view from which to draw conclusions about its author and her era.

— Kathryn Metz on the song's inclusion in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[111]

"Rhythm Nation" is among Jackson's signature songs, commended for its lyrical theme and innovative production. Jackson commented, "When I first proposed a socially conscious concept, there were voices of doubt. But the more I thought about it, the more committed I became, I no longer had a choice. The creativity took over, "Rhythm Nation" came alive. I saw that a higher power was at work."[7] Jon Pareles declared it "one of the more innovative Top 10 hits of the 1980's", while Yahoo! Music called it "revolutionary" and "militaristic."[114][115] Michael Saunders considered it among Jackson's repertoire of "skillfully packaged pop songs that have made her one of the biggest-selling performers in popdom."[19] Jimmy Jam stated, "Janet has said a million times, "You're not going to change anybody. But if you've got somebody on the fence, and they're at that point when they're either going to go one way or another, then a little nudge in that direction ain't gonna hurt." So that's all you're trying to do. And it's cool to do that. It's cool to do that and have a hit."[6]

Slant Magazine ranked it among the best singles of the 1980s, saying, "the music is militant and regimented, with beats that fire like artillery juxtaposed with the typically thin-voiced Janet's unbridled vocal performance."[23] The publication added, "Rhythm Nation" makes its statement without relying on schmaltz; it's no wonder why big brother Mike was envious of it."[23] The song was later ranked number twenty-one on their list of "100 Greatest Dance Songs", praising Jackson's "guarded political optimism into a direct attack on the 1980s' culture of indifference."[112] Richard Croft praised its "powerful" production, declaring, "the beats on this song are probably the most powerful ever to be heard in the history of mankind."[25] Another critique declared it "the best song Janet has ever done", praising its "mission statement" in addition to its "frantic beats, the message, the determined vocal performance, the lyrics and the explosive chorus", adding "There are few moments in pop music as thrilling as the transition of the dance breakdown into the final choruses, complete with Janet going nuts over the ad-libs, as if she was in a trance brought on but just how beyond amazing this song is. And that's not even mentioning the incredible video."[116]

The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[117]

Philanthropy

[edit]Through words and deeds, Janet has set an example of generosity, of empowerment, of tolerance, while leading an array of efforts addressing some of society's greatest challenges.

— Kam Williams on Jackson's philanthropy.[118]

Jackson founded the "Rhythm Nation Scholarship", assisting students in meeting their academic goals. The monetary award is given to students who have demonstrated high academic achievement or have been actively involved within their school or community.[119] She received the Chairman's Award at the NAACP Awards for her work regarding illiteracy, drug abuse, violence, and high school dropout prevention. In response to a critic who said her socially conscious lyrics could accomplish "nothing", Jackson invited two high school graduates to the stage, who both had previously credited the song and its music video as the motivation for staying in school.[120] Various portions of the "Rhythm Nation" outfit were donated to charity, including the Music Against AIDS auction.[121] A tribute band known as "Rhythm Nation" performs at various fundraisers, including benefits for children with cancer at the Ronald McDonald House in New York City.[122][123][124]

Effect of resonant frequencies

[edit]In August 2022, Microsoft engineer Raymond Chen published an article detailing how playing the music video on or nearby certain laptops would cause a crash. The song contains one of the natural resonant frequencies to some 5400 RPM OEM-laptop hard drives used around the year 2005.[125] This vulnerability was assigned a CVE ID of CVE-2022-38392, which describes a possible denial of service attack, and references Raymond Chen's blog post. YouTuber Adam Neely traced the song's resonant peak at 84.2 Hz, which he hypothesized as the combination of the song's bassline at the note E with a possible use of pitch control to increase the speed and pitch of the song during production, as the source of the offending resonant frequency.[126]

Official versions and remixes

[edit]

|

|

Track listings

[edit]|

US promo CD[128]

Canadian cassette single, European 7-inch single, and Japanese mini-CD single[129][130][131]

Canadian and European 12-inch single[132][133]

UK CD single[134]

UK 12-inch single[135]

|

UK cassette single[136]

European CD single[137]

Japanese CD maxi-single[138]

|

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United States (RIAA)[36] | Platinum | 1,000,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

[edit]- List of number-one dance singles of 1989 (U.S.)

- List of number-one dance singles of 1990 (U.S.)

- R&B number-one hits of 1990 (USA)

References

[edit]- ^ "New Singles". Music Week. October 21, 1989. p. 41.

- ^ "Red Bull Music Academy Daily". daily.redbullmusicacademy.com.

- ^ Matos, Michaelangelo (September 9, 2019). "Why Janet Jackson Recorded Rhythm Nation in Minnesota". MSPMAPS. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bronson, Fred (2003). Rhythm Nation. Billboard Book of Number One Hits. p. 744.

- ^ a b c d Janet Jackson. Johnson, Robert E. February 1990.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Jam & Lewis: Hot House & Serious Soul With The Magicians Of Minneapolis. Widders-Ellis, Andy. May 1990. p. 27.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Janet's Nation. Ritz, David. March 1990.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Jackson's Heights. Us Magazine. March 5, 1990.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Ain't I A Woman?. Upscale. January 1996. p. 24.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Janet Jackson Finally Learns to Say 'I'". Los Angeles Times. April 15, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Janet Jackson. Curtis, Anthony E. February 22, 1990.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ripani, Richard J. (2006), The New Blue Music: Changes in Rhythm & Blues, 1950–1999, Univ. Press of Mississippi, pp. 131–132, 152–153, ISBN 1-57806-862-2

- ^ "Janet Jackson: Damita Jo - Music Review - Slant Magazine". Slant Magazine. Cinquemani, Sal. March 23, 2004. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Rhythm Nation 1814 - Album Reviews - Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Aletti, Vince. October 19, 1989. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Janet Jackson "Rhythm Nation" Sheet Music - Download & Print". MusicNotes.com. March 30, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Pop View – Do Songs About The World's Ills Do Any Good?". New York Times. January 7, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Janet Jackson, 'Rhythm Nation 1814' - Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Women Who Rock: The 50 Greatest Albums of All Time: Janet Jackson, 'Rhythm Nation' - Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. June 22, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Janet's Reckoning". The Sun Sentinel. Saunders, Michael. October 7, 1997. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Janet Jackson - Rhythm Nation 1814 (album review)". Sputnik Music. Powell, Zachary. February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Picks and Pans Review: Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814". People Magazine. November 20, 1989. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Movie Reviews and News - EW.com". Entertainment Weekly. January 19, 1996. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c "The 100 Best Singles of the 1980s". Slant Magazine. August 20, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Arnold, Chuck (May 16, 2016). "Janet Jackson's 50 best songs of all time, ranked". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "20. Janet Jackson – 'Rhythm Nation' (1989)". Wordpress. Croft, Richard. June 1, 2010. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ You've Come A Long Way, Baby: Women, Politics, and Popular Culture. Goren, Lilly. May 22, 2009. ISBN 9780813173405. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Willman, Chris (April 23, 1990). "POP MUSIC REVIEW: Janet Jackson's Dance of Community". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "Are You A Part of the Rhythm Nation". Afro-punk.com. March 7, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pop Review – At the Mercy of Lust, Yet in Total Control - Page 2 - New York Times". New York Times. July 18, 1998. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Recordings – Janet Jackson Adopts a New Attitude: Concern - New York Times". New York Times. September 17, 1998. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Capitalizing On Jackson Tempest - Page 2 - New York Times". New York Times. February 4, 2004. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Review/Pop; Janet Jackson Fleshes Out Her Own Video Image". New York Times. March 17, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Rhythm Nation – Crossing Crossroads". Wordpress. Torrenueva, Christopher. February 13, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Top 100 Songs | Billboard Hot 100 Chart". Billboard.

- ^ a b c d Jackson Number Ones. Halstead, Craig. 2003. ISBN 9780755200986. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "American single certifications – Janet Jackson – Rhythm Nation". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010. Mt. Martha, VIC, Australia: Moonlight Publishing.

- ^ a b "Janet Jackson – Rhythm Nation" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Singles: Issue 6658." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Janet Jackson – Rhythm Nation". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Janet Jackson: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution. Tannenbaum, Rob. October 27, 2011. p. 179. ISBN 9781101526415. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Millennium Dance Complex". Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Janet Jackson Sweeps Music Awards : Pop: The singer wins eight Billboard prizes, matching Michael's 1984 Grammy performance". Los Angeles Times. November 17, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Past Winners Search - GRAMMY.com". Grammy.com. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "100 Greatest Music Videos - Feature - Slant Magazine". Slant Magazine. Gonzalez, Ed. June 26, 2003. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "'Glee' recap: No Strings Attached". Entertainment Weekly. November 29, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Ten Best Apocalyptic Dance Music Videos". Rolling Stone. April 6, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "'Alejandro' Video Preview: Lady Gaga Tips Her Hat To Madonna And Janet Jackson". MTV. Anderson, Kyle. June 2, 2010. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Live on TOTPs". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Janet Jackson - Rhythm Nation - Peters Popshow". YouTube. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "WORLD Celebrities react to the death of Queen Elizabeth II: Elton John, Mick Jagger, Helen Mirren and many more". CBS News. September 9, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ "Janet Jackson Talks Tour On 'Paul O'Grady', Joe Jonas Performs "See No More"". Idolator. July 2, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Ellen Gets Down with Janet". Ellentv.com. May 16, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "America United Concert - Rhythm Nation". YouTube. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Nipple Ripples: 10 Years of Fallout From Janet Jackson's Halftime Show". Rolling Stone. Kreps, Daniel. January 30, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "YouTube Inventors and Founders Profile". About.com. Bellis, Mary. 2005. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "In the Beginning, There Was a Nipple". ESPN. Cogan, Marin. January 28, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pop View – Ballet, Boogie, Rap, Tap and Roll". New York Times. August 26, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Short Takes: Tokyo Fans Cheer Janet Jackson". Dunning, Jennifer. May 18, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pop View – Ballet, Boogie, Rap, Tap and Roll". New York Times. August 26, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Making Music Without a Sound". LA Times. Ikenberg, Tamara. November 20, 1998. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Don't overplan it, Janet". Daily Telegraph. Briggs, Simon. June 9, 1998. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Janet displays her crowd control". USA Today. 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Ms. Janet Jackson Gets Nasty". Rolling Stone. Sheppard, Denise. July 10, 2001. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pop Review – Channel Surfing With a Diva, From BET to Playboy". New York Times. August 22, 2001. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pop review: Janet Jackson - The Guardian". The Guardian. Clarke, Betty. July 27, 2001. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Janet Jackson: The Number Ones Up Close And Personal Tour Live At Mohegan Sun on March 16 (Concert Review)", MuuMuse, Stern, Bradley, March 2011, retrieved March 9, 2012

- ^ "Janet Jackson – review". The Guardian. Petridis, Alexis. July 1, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (September 1, 2015). "Review: Janet Jackson, on Unbreakable Tour, Shows Off Her Demure Side". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Readers Pick Their 10 Favorite Dancing Musicians". Rolling Stone. July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Action Jacksons - Michael Jackson Remembered - EW.com". Entertainment Weekly. Seymour, Craig. December 7, 1999. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Sweat, Tears, and Jazz Hands: The Official History of Show Choir from Vaudeville to Glee. Weaver, Mike. 2011. ISBN 9781557837721. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome To Planet Janet: It's Our World". The Sun Sentinel. Winston, Sherri. March 18, 2001. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Alexis Krauss of Sleigh Bells Chats With Glamour About New Album Bitter Rivals and Her Pop-Culture Obsessions". Glamour. Woods, Mickey. October 8, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Jamie Lidell: soul man turns the page". The Independent. Bray, Elisa. January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Important points regarding Kylie's new single and album". Popjustice. April 26, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "[Interview] Record producer Yoo Young-jin - Part 1". Asiae.co.kr. June 11, 2010. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Janet Jackson Has The Best Music Videos In The History Of Music Videos". BuzzFeed. Zafar, Aylin. December 7, 2005. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Justin Timberlake Interview 1998 RAW". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021.

- ^ "Here Is Lady Gaga's "Alejandro" Video, Finally". Village Voice. Harvilla, Rob. June 8, 2010. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Peter Andre's Defender by Peter Falloon - Promo News". Promo News. Falloon, Peter. March 8, 2010. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "OK Go Have Another Homemade Clip In The Can". Montogomery, James. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Picks and Pans Review: Nicki Minaj's Top 5 Style Idols - People.com". People.com. December 6, 2010. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Grammys 2011 Belong To Arcade Fire, Lady Antebellum". MTV. Kaufman, Gil. February 14, 2011. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Jessie Ware Channels A Little Janet Jackson, A Little Madonna For "Imagine It Was Us"". VH1. Viera, Bene. April 9, 2013. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Teen Queen Britney Does It Again!". Orlando Sentinel. Moore, Roger. September 10, 2000. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "The MTV Video Music Awards: A Running Diary". Village Voice. Briehan, Tom. August 1, 2006. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Inside the 2010 BRIT Award". Dose. Collins, Leah. October 18, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "We Went To Rihanna's Diamonds World Tour New York Show And The Outfits Were Amazing". MTV Style. May 8, 2013. Archived from the original on June 19, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Kate Hudson Interview – Something Borrowed". Collider. Radish, Christina. 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Michael K. Williams on Playing Omar on 'The Wire,' Discovering Snoop, and How Janet Jackson Changed His Life". January 2, 2008. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Initiation: 'Trons Elizabeth Mathis Is Our Wonder Woman". Vibe. Mathis, Elizabeth. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2010.

- ^ "Dance – Reality-Show Pop Stars Need a Choreographer, Too". Gladstone, Valerie. April 1, 2001. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "The Choreographers: Wade Robson learns to dance like a penguin". King, Susan. November 6, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JiRTim8wVBI Janet Jackson- Icon promo on TRL

- ^ "Nasty / Rhythm Nation (Glee Cast Version) - Single". iTunes. November 25, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ "Crystal Kay to voice act for Japanese dubbed version of "Happy Feet 2"". Tokyo Hive. Oricon. October 19, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ SNSD - Rhythm Nation on YouTube

- ^ After School - Rhythm Nation on YouTube

- ^ "Oneohtrix Point Never Covers Janet Jackson's "Rhythm Nation" for KENZO Fashion Show". Pitchfork. February 20, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ "Stereo Hogzz Wow Simon Cowell With 'Rhythm Nation' Performance on 'X Factor'". Popcrush. Maher, Cristin. November 2, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Diversity Dance Troupe Land a Gig in a 3D Film". June 3, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Stars in Their Eyes - Janet Jackson". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "'America's Best Dance Crew 2': Exclusive peek at Janet Jackson episode". Los Angeles Times. July 11, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Jaya Live at the Araneta". AllMusic. 2001. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 15, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ "Three New "Legends In Concert" To Debut on Norwegian Epic: Janet Jackson, Neil Diamond And Aretha Franklin". NCL.com. January 7, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "A shrine to women artists". Stump, Douglas. Lebanon Daily News. November 27, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "'Women Who Rock': Janet Jackson : Janet Jackson - fox8.com". Fox News. February 23, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ a b "A Bright Rhythm Nation". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Metz, Kathryn. November 28, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "100 Greatest Dance Songs". Slant Magazine. January 30, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Hunt, Dennis (March 16, 1990). "The Award That Soul Train Didn't Bestow". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ "Review/Pop; Wrapped in Song and Spectacle, Janet Jackson Plays the Garden". The New York Times. December 20, 1993. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pays Tribute To Janet, TLC, Supremes In 'Pretty Girl Rock' Video". Yahoo! Music. Johnson Jr, Billy. November 17, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Classic Album: Janet Jackson – Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814". The Gospel According To Richard Eric. Eric, Richard. October 11, 2011. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Robert Dimery; Michael Lydon (February 7, 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 0-7893-1371-5.

- ^ "Conversations with Janet Jackson - Global Grind". Global Grind. Fuller, James. November 5, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Janet – Causes". JanetJackson.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "NAACP Winners: Just a Beginning". Los Angeles Times. January 13, 1992. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Now Hard Rockers, Rappers Spread AIDS Warning Too". Los Angeles Times. October 13, 1989. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Rhythm Nation - Rock & Pop Function Band for Hire - East Suffix". Warble-Entertainment. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Benefits – New York Times". New York Times. January 9, 2000. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ "Benefits – New York Times". New York Times. April 27, 2003. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Chen, Raymond (August 16, 2022). "Janet Jackson had the power to crash laptop computers". The Old New Thing. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ This Janet Jackson BASSLINE breaks laptops, retrieved September 11, 2022

- ^ "And the OSCar goes to... Lee Groves". G-Force Software. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Rhythm Nation (US promo CD liner notes). Janet Jackson. A&M Records, JDJ Entertainment, Joe Jackson Productions, Inc. 1989. CD 17915.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (Canadian cassette single sleeve). Janet Jackson. A&M Records. 1989. TS1455.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (European 7-inch single sleeve). Janet Jackson. A&M Records. 1989. 390 468-7.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ リズム・ネイション (Japanese mini-CD single liner notes). Janet Jackson. A&M Records. 1989. PCDY-10008.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (Canadian 12-inch single sleeve). Janet Jackson. A&M Records. 1989. SP-12335.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (European 12-inch single sleeve). Janet Jackson. A&M Records. 1989. 390 468-1.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (UK CD single liner notes). Janet Jackson. Breakout Records. 1989. USACD 673.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (UK 12-inch single sleeve). Janet Jackson. Breakout Records. 1989. USAT 673.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (UK cassette single sleeve). Janet Jackson. A&M Records. 1989. USATC 673.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Rhythm Nation (European CD single liner notes). Janet Jackson. A&M Records. 1989. 390 468-2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ リズム・ネイション (Japanese maxi-single liner notes). Janet Jackson. A&M Records, JDJ Entertainment, Joe Jackson Productions, Inc. 1990. PCCY-10084.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Lwin, Nanda (2000). Top 40 Hits: The Essential Chart Guide. Music Data Canada. p. 140. ISBN 1-896594-13-1.

- ^ "Top RPM Dance/Urban: Issue 6653." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Eurochart Hot 100 Singles" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 6, no. 47. November 25, 1989. p. IV. OCLC 29800226 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Rhythm Nation". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "JANET(ジャネット・ジャクソン)のシングル売り上げランキング" (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 50, 1989" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Janet Jackson – Rhythm Nation" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ Halstead, Craig; Cadman, Chris (2003). Jackson Number Ones. Authors Online Ltd. p. 38.

- ^ "Janet Jackson – Rhythm Nation". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Janet Jackson Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Janet Jackson Chart History (Dance Club Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Janet Jackson Chart History (Dance Singles Sales)". Billboard. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ "Janet Jackson Chart History (Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 Singles – Week ending December 30, 1989". Cash Box. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "'90 Top 15 Records". Radio & Records. December 14, 1990. p. 57. ProQuest 1017245303.

- ^ "'90 Top 15 Records". Radio & Records. December 14, 1990. p. 61. ProQuest 1017250230.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Janet Jackson – Rhythm Nation" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Hit Tracks of 1990". RPM. Vol. 53, no. 6. December 22, 1990. p. 8. ISSN 0315-5994 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Top 50 Dance Tracks of 1990". RPM. Vol. 53, no. 6. December 22, 1990. p. 18. ISSN 0315-5994 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Hot 100 Songs – Year-End 1990". Billboard. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Dance Club Songs – Year-End 1990". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "1987 The Year in Music & Video – Top Dance Sales 12-Inch Singles" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 102, no. 52. December 22, 1990. p. YE-31. ISSN 0006-2510 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs – Year-End 1990". Billboard. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Top 90 of '90". Radio & Records. December 14, 1990. p. 56. ProQuest 1017245278.

- ^ "Top 90 of '90". Radio & Records. December 14, 1990. p. 60. ProQuest 1017250211.