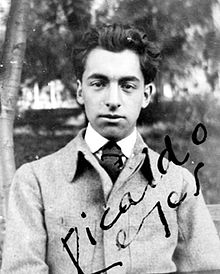

Pablo Neruda

Pablo Neruda | |

|---|---|

Neruda in 1963 | |

| Born | Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto 12 July 1904 Parral, Maule Region, Chile |

| Died | 23 September 1973 (aged 69) Santiago, Chile |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Communist |

| Spouses | Marijke Antonieta Hagenaar Vogelzang

(m. 1930; div. 1942)Delia del Carril

(m. 1943; div. 1955) |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards | |

| Signature | |

| |

Pablo Neruda (/nəˈruːdə/ nə-ROO-də;[1] Spanish pronunciation: [ˈpaβlo neˈɾuða] ; born Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto; 12 July 1904 – 23 September 1973) was a Chilean poet-diplomat and politician who won the 1971 Nobel Prize in Literature.[2] Neruda became known as a poet when he was 13 years old and wrote in a variety of styles, including surrealist poems, historical epics, political manifestos, a prose autobiography, and passionate love poems such as the ones in his collection Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair (1924).

Neruda occupied many diplomatic positions in various countries during his lifetime and served a term as a senator for the Chilean Communist Party. When President Gabriel González Videla outlawed communism in Chile in 1948, a warrant was issued for Neruda's arrest. Friends hid him for months, and in 1949, he escaped through a mountain pass near Maihue Lake into Argentina; he would not return to Chile for more than three years. He was a close advisor to Chile's socialist president Salvador Allende, and when he got back to Chile after accepting his Nobel Prize in Stockholm, Allende invited him to read at the Estadio Nacional before 70,000 people.[3]

Neruda was hospitalized with cancer in September 1973, at the time of the coup d'état led by Augusto Pinochet that overthrew Allende's government, but returned home after a few days when he suspected a doctor of injecting him with an unknown substance for the purpose of murdering him on Pinochet's orders.[4] Neruda died at his home in Isla Negra on 23 September 1973, just hours after leaving the hospital. Although it was long reported that he died of heart failure, the interior ministry of the Chilean government issued a statement in 2015 acknowledging a ministry document indicating the government's official position that "it was clearly possible and highly likely" that Neruda was killed as a result of "the intervention of third parties".[5] However, an international forensic test conducted in 2013 rejected allegations that he was poisoned.[6][7]

Neruda is often considered the national poet of Chile, and his works have been popular and influential worldwide. The Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez once called him "the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language",[8] and the critic Harold Bloom included Neruda as one of the writers central to the Western tradition in his book The Western Canon.

Early life

[edit]

Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto was born on 12 July 1904, in Parral, Chile,[9] a city in Linares Province, now part of the greater Maule Region, some 350 km south of Santiago.[10] His father, José del Carmen Reyes Morales, was a railway employee, and his mother Rosa Neftalí Basoalto Opazo was a school teacher who died on 14 September two months after he was born. On 26 September, he was baptized in the parish of San Jose de Parral.[11] Neruda grew up in Temuco with Rodolfo and a half-sister, Laura Herminia "Laurita," from one of his father's extramarital affairs (her mother was Aurelia Tolrà, a Catalan woman).[12] He composed his first poems in the winter of 1914.[13] Neruda was an atheist.[14]

Literary career

[edit]something started in my soul,

fever or forgotten wings,

and I made my own way,

deciphering

that fire

and wrote the first faint line,

faint without substance, pure

nonsense,

pure wisdom,

of someone who knows nothing,

and suddenly I saw

the heavens

unfastened

and open.

From "Poetry", Memorial de Isla Negra (1964).

Trans. Alastair Reid.[15]

Neruda's father opposed his son's interest in writing and literature, but he received encouragement from others, including the future Nobel Prize winner Gabriela Mistral, who headed the local school. On 18 July 1917, at the age of 13, he published his first work, an essay titled "Entusiasmo y perseverancia" ("Enthusiasm and Perseverance") in the local daily newspaper La Mañana, and signed it Neftalí Reyes.[16] From 1918 to mid-1920, he published numerous poems, such as "Mis ojos" ("My eyes"), and essays in local magazines as Neftalí Reyes. In 1919, he participated in the literary contest Juegos Florales del Maule and won third place for his poem "Comunión ideal" or "Nocturno ideal." By mid-1920, when he adopted the pseudonym Pablo Neruda, he was a published author of poems, prose, and journalism. He is thought to have derived his pen name from the Czech poet Jan Neruda,[17][18][19] though other sources say the true inspiration was Moravian violinist Wilma Neruda, whose name appears in Arthur Conan Doyle's novel A Study in Scarlet.[20][21]

In 1921, at the age of 16, Neruda moved to Santiago[15] to study French at the Universidad de Chile with the intention of becoming a teacher. However, he soon devoted all his time to writing poems, and with the help of well-known writer Eduardo Barrios,[22] he managed to meet and impress Don Carlos George Nascimento, the most important publisher in Chile at the time. In 1923, his first volume of verse, Crepusculario (Book of Twilights), was published by Editorial Nascimento, followed the next year by Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada (Twenty Love Poems and A Desperate Song),[15] a collection of love poems that was controversial for its eroticism, especially considering its author's young age. Both works were critically acclaimed and have been translated into many languages. A second edition of Veinte poemas appeared in 1932. In the years since its publication, millions of copies have been sold, and it became Neruda's best-known work. Almost 100 years later, Veinte Poemas is still the best-selling poetry book in the Spanish language.[15] By the age of 20, Neruda had established an international reputation as a poet but faced poverty.[15]

In 1926, Neruda published the collection tentativa del hombre infinito (venture of the infinite man) and the novel El habitante y su esperanza (The Inhabitant and His Hope).[23] In 1927, out of financial desperation, he took an honorary consulship in Rangoon, the capital of the British colony of Burma, then administered from New Delhi as a province of British India.[23] Later, mired in isolation and loneliness, he worked in Colombo (Ceylon), Batavia (Java), and Singapore.[24] In Batavia the following year, he met and married (December 6, 1930) his first wife, a Dutch bank employee named Marijke Antonieta Hagenaar Vogelzang (born as Marietje Antonia Hagenaar),[25] known as Maruca.[26] While he was in the diplomatic service, Neruda read large amounts of verse, experimented with many different poetic forms, and wrote the first two volumes of Residencia en la Tierra, which include many surrealist poems.

In 1950, Neruda wrote a famous poem, “United Fruit Company,” referencing the United Fruit Company, founded in 1899, that controlled many territories and transportation networks in Latin America. He was a communist who believed corporations such as this were exploiting Latin America and hurting them. The corporation was corrupt and had a quest for wealth, and throughout his poem, he speaks of how the innocent citizens of Latin America suffered when companies destroyed their land and lifestyles and brought cruelty and injustices to their land. He points out ways that companies manipulate governments and workers in attempts to be greedy towards impoverished countries.

As a political activist, his stance as a communist comes out in his poem as he calls the wealthy corporations “bloodthirsty flies” and resembles a “dictatorship.” He compares United Fruit Inc. to big-name companies such as Coca-Cola and Ford Motors to emphasize their strength and power over the little countries residing in Latin America. In addition, his writing skills truly came out in this poem, solidifying his worthiness of being named the National Poet of Chile. In this poem, he used tons of imagery, metaphors, irony, symbolism, and an overall witty tone to get his point of dislike towards big corrupt corporations and promotion of communism.[tone]

Diplomatic and political career

[edit]Spanish Civil War

[edit]After returning to Chile, Neruda was given diplomatic posts in Buenos Aires and then Barcelona, Spain.[27] He later succeeded Gabriela Mistral as consul in Madrid, where he became the center of a lively literary circle, befriending such writers as Rafael Alberti, Federico García Lorca, and the Peruvian poet César Vallejo.[27] His only offspring, his daughter Malva Marina (Trinidad) Reyes, was born in Madrid in 1934, the product of his first marriage to María Antonia Hagenaar Vogelzang. Reyes was plagued with severe health problems, particularly suffering from hydrocephalus.[28] She died in 1943 at the age of eight, having spent most of her short life with a foster family in the Netherlands after Neruda ignored and abandoned her, forcing her mother to work solely to support her care.[29][30][31][32] Half of that time was during the Nazi occupation of Holland, when the Nazi view of birth defects was that they denoted genetic inferiority. During this period, Neruda became estranged from his wife and instead began a relationship with Delia del Carril, an aristocratic Argentine artist who was 20 years his senior. Reyes was repudiated, mocked, and abandoned by her father and died in utter indigence when she was 8 years old in war-devastated and Nazi-occupied Netherlands.[33]

As Spain became engulfed in civil war, Neruda became intensely politicized for the first time. His experiences during the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath moved him away from privately focused work in the direction of collective obligation. Neruda became an ardent Communist for the rest of his life. The radical leftist politics of his literary friends, as well as that of del Carril, were contributing factors, but the most important catalyst was the execution of García Lorca by forces loyal to the dictator Francisco Franco.[27] Through his speeches and writings, Neruda threw his support behind the Spanish Republic, publishing the collection España en el corazón (Spain in Our Hearts, 1938). He lost his post as consul due to his political militancy.[27] In July 1937, he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals toward the war in Spain, held in Valencia, Barcelona, and Madrid and attended by many writers including André Malraux, Ernest Hemingway, and Stephen Spender.[34]

Neruda's marriage to Vogelzang broke down, and he eventually obtained a divorce in Mexico in 1943. His estranged wife moved to Monte Carlo to escape the hostilities in Spain and then to the Netherlands with their very ill only child, and he never saw either of them again.[35] After leaving his wife, Neruda lived with Delia del Carril in France, eventually marrying her (shortly after his divorce) in Tetecala in 1943; however, his new marriage was not recognized by Chilean authorities as his divorce from Vogelzang was deemed illegal.[36]

Following the election of Pedro Aguirre Cerda (whom Neruda supported) as President of Chile in 1938, Neruda was appointed special Consul for Spanish emigrants in Paris. There he was responsible for what he called "the noblest mission I have ever undertaken": transporting 2,000 Spanish refugees who had been housed by the French in squalid camps to Chile on an old ship called the Winnipeg.[37] Neruda is sometimes charged with having selected only fellow Communists for emigration, to the exclusion of others who had fought on the side of the Republic.[38] Many Republicans and Anarchists were killed during the German invasion and occupation. Others deny these accusations, pointing out that Neruda chose only a few hundred of the 2,000 refugees personally; the rest were selected by the Service for the Evacuation of Spanish Refugees set up by Juan Negrín, President of the Spanish Republican Government in Exile.

Mexican appointment

[edit]Neruda's next diplomatic post was as Consul General in Mexico City from 1940 to 1943.[39] During his time there, he married del Carril and learned that his daughter Malva had died at the age of eight in Nazi-occupied Netherlands.[39] In 1940, following the failed assassination attempt against Leon Trotsky, Neruda arranged a Chilean visa for the Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros, who had been accused of involvement in the conspiracy to assassinate Trotsky.[40] Neruda later stated that he had done it at the request of the Mexican President, Manuel Ávila Camacho. This allowed Siqueiros, who was then imprisoned, to leave Mexico for Chile, where he stayed at Neruda's private residence. In return for Neruda's assistance, Siqueiros spent over a year painting a mural at a school in Chillán. While Neruda's relationship with Siqueiros drew criticism, he dismissed the allegation that his intent had been to aid an assassin as "sensationalist politico-literary harassment".

Return to Chile

[edit]In 1943, upon his return to Chile, Neruda embarked on a tour of Peru, where he visited Machu Picchu.[41] This experience later inspired Alturas de Macchu Picchu, a book-length poem in 12 parts that he completed in 1945. The poem expressed his growing awareness of and interest in the ancient civilizations of the Americas. He further explored this theme in Canto General (1950). In Alturas, Neruda celebrated the achievement of Macchu Picchu but also condemned the slavery that had made it possible. In Canto XII, he called upon the dead of many centuries to be reborn and speak through him. Martín Espada, a poet and professor of creative writing at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, has hailed the work as a masterpiece, declaring that "there is no greater political poem".

Communism

[edit]Bolstered by his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, Neruda, like many left-leaning intellectuals of his generation, came to admire the Soviet Union of Joseph Stalin. He did so partly due to the role it played in defeating Nazi Germany and partly because of an idealistic interpretation of Marxist doctrine.[42] This sentiment is echoed in poems such as Canto a Stalingrado ("Song to Stalingrad") (1942) and Nuevo canto de amor a Stalingrado ("New Love Song to Stalingrad") (1943). In 1953, Neruda was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize. Upon Stalin's death that same year, Neruda wrote an ode to him, as he also wrote poems in praise of Fulgencio Batista, Saludo a Batista ("Salute to Batista"), and later, Fidel Castro. His fervent Stalinism eventually drove a wedge between Neruda and his long-time friend, Mexican poet Octavio Paz, who commented that "Neruda became more and more Stalinist, while I became less and less enchanted with Stalin."[43] Their differences came to a head after the Nazi-Soviet Ribbentrop–Molotov Pact of 1939, when they almost came to blows in an argument over Stalin. Although Paz still considered Neruda "The greatest poet of his generation", in an essay on Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, he wrote that when he thinks of "Neruda and other famous Stalinist writers and poets, I feel the gooseflesh that I get from reading certain passages of the Inferno. No doubt they began in good faith ... but insensibly, commitment by commitment, they saw themselves becoming entangled in a mesh of lies, falsehoods, deceits, and perjuries, until they lost their souls."[44] On 15 July 1945, at Pacaembu Stadium in São Paulo, Brazil, Neruda read to 100,000 people in honor of the Communist revolutionary leader Luís Carlos Prestes.[45]

Neruda hailed Vladimir Lenin as the "great genius of this century". In a speech he gave on 5 June 1946, Neruda also paid tribute to the late Soviet leader Mikhail Kalinin, whom Neruda regarded as a "man of noble life," "the great constructor of the future," and "a comrade in arms of Lenin and Stalin."[46] Neruda later came to regret his fondness for the Soviet Union, explaining that "in those days, Stalin seemed to us the conqueror who had crushed Hitler's armies."[42] Of a subsequent visit to China in 1957, Neruda wrote: "What has estranged me from the Chinese revolutionary process has not been Mao Tse-tung but Mao Tse-tungism." He labeled this Mao Tse-Stalinism as "the repetition of a cult of a Socialist deity".[42] Despite his disillusionment with Stalin, Neruda never lost his fundamental faith in communist theory and remained loyal to the Communist party. Anxious not to provide ammunition to his ideological enemies, he would later refuse publicly to condemn the Soviet repression of dissident writers like Boris Pasternak and Joseph Brodsky, an attitude with which even some of his staunchest admirers disagreed.[47]

On 4 March 1945, Neruda was elected as a Communist Senator representing the northern provinces of Antofagasta and Tarapacá in the Atacama Desert.[48][49] He officially joined the Communist Party of Chile four months later.[39] In 1946, the Radical Party's presidential candidate, Gabriel González Videla, asked Neruda to act as his campaign manager. González Videla was supported by a coalition of left-wing parties, and Neruda fervently campaigned on his behalf. However, once in office, González Videla turned against the Communist Party and enacted the Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia (Law of Permanent Defense of the Democracy). The breaking point for Senator Neruda was the violent repression of a Communist-led miners' strike in Lota in October 1947 when striking workers were herded into island military prisons and a concentration camp in the town of Pisagua. Neruda's criticism of González Videla culminated in a dramatic speech in the Chilean senate on 6 January 1948, which became known as "Yo acuso" ("I accuse"), during which he read out the names of the miners and their families who were imprisoned at the concentration camp.[50]

In 1959, Neruda was present when Fidel Castro was honored at a welcoming ceremony hosted by the Central University of Venezuela. There, he spoke to a massive gathering of students and read his poem Un canto para Bolívar ("A Song for Bolívar"). Prior to this, he shared his sentiments: "In this painful and victorious hour that the peoples of the Americas are living, my poem, with changes in location, can be understood as directed towards Fidel Castro, because in the struggles for freedom, the destiny of a man always emerges to instill confidence in the spirit of greatness in the history of our nations."[51] During the late 1960s, Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges was asked for his opinion on Neruda. Borges stated, "I think of him as a very fine poet, a very fine poet. I don't admire him as a man; I think of him as a very mean man."[52] He said that Neruda had not spoken out against Argentine President Juan Perón because he was afraid to risk his reputation, noting "I was an Argentine poet; he was a Chilean poet; he's on the side of the Communists; I'm against them. So I felt he was behaving very wisely in avoiding a meeting that would have been quite uncomfortable for both of us."[53]

Hiding and exile, 1948–1952

[edit]

A few weeks after his "Yo acuso" speech in 1948, finding himself threatened with arrest, Neruda went into hiding. He and his wife were smuggled from house to house, hidden by supporters and admirers for the next 13 months.[39] While in hiding, Senator Neruda was removed from office, and in September 1948, the Communist Party was banned altogether under the Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia, called by critics the Ley Maldita (Accursed Law), which eliminated over 26,000 people from the electoral registers, thus stripping them of their right to vote. Neruda later moved to Valdivia in southern Chile. From Valdivia, he moved to Fundo Huishue, a forestry estate in the vicinity of Huishue Lake. Neruda's life underground ended in March 1949 when he fled over the Lilpela Pass in the Andes Mountains to Argentina on horseback. He would dramatically recount his escape from Chile in his Nobel Prize lecture.

Once out of Chile, he spent the next three years in exile.[39] In Buenos Aires, Neruda took advantage of the slight resemblance between him and his friend, the future Nobel Prize-winning novelist and cultural attaché to the Guatemalan embassy, Miguel Ángel Asturias, to travel to Europe using Asturias' passport.[54] Pablo Picasso arranged his entrance into Paris, and Neruda made a surprise appearance there to a stunned World Congress of Peace Forces[clarification needed], while the Chilean government denied that the poet could have escaped the country.[54] Neruda spent those three years traveling extensively throughout Europe as well as taking trips to India, China, Sri Lanka, and the Soviet Union. His trip to Mexico in late 1949 was lengthened due to a serious bout of phlebitis.[55] A Chilean singer named Matilde Urrutia was hired to care for him, and they began an affair that would, years later, culminate in marriage.[55] During his exile, Urrutia would travel from country to country, shadowing him, and they would arrange meetings whenever they could. Matilde Urrutia was the muse for Los versos del capitán, a book of poetry that Neruda later published anonymously in 1952.

from "Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon"

Full woman, fleshly apple, hot moon,

thick smell of seaweed, crushed mud and light,

what obscure brilliance opens between your columns?

What ancient night does a man touch with his senses?

Loving is a journey with water and with stars,

with smothered air and abrupt storms of flour:

loving is a clash of lightning-bolts

and two bodies defeated by a single drop of honey.

From "Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon",

Selected Poems translated by Stephen Mitchell (1997) [56]

While in Mexico, Neruda also published his lengthy epic poem Canto General, a Whitmanesque catalog of the history, geography, and flora and fauna of South America, accompanied by Neruda's observations and experiences. Many of them dealt with his time underground in Chile, during which he composed much of the poem. In fact, he had carried the manuscript with him during his escape on horseback. A month later, a different edition of 5,000 copies was boldly published in Chile by the outlawed Communist Party, based on a manuscript Neruda had left behind. In Mexico, he was granted honorary Mexican citizenship.[57] Neruda's 1952 stay in a villa owned by Italian historian Edwin Cerio on the island of Capri was fictionalized in Antonio Skarmeta's 1985 novel Ardiente Paciencia (Ardent Patience, later known as El cartero de Neruda, or Neruda's Postman), which inspired the popular film Il Postino (1994).[58]

Second return to Chile

[edit]

By 1952, the González Videla government was on its last legs, weakened by corruption scandals. The Chilean Socialist Party was in the process of nominating Salvador Allende as its candidate for the September 1952 presidential elections and was keen to have the presence of Neruda, by now Chile's most prominent left-wing literary figure, to support the campaign.[57] Neruda returned to Chile in August of that year and rejoined Delia del Carril, who had traveled ahead of him some months earlier, but the marriage was crumbling. Del Carril eventually learned of his affair with Matilde Urrutia, and he sent her back to Chile in 1955.[clarification needed] She convinced the Chilean officials to lift his arrest,[clarification needed] allowing Urrutia and Neruda to go to Capri, Italy.[clarification needed] Now united with Urrutia, Neruda would, aside from many foreign trips and a stint as Allende's ambassador to France from 1970 to 1973, spend the rest of his life in Chile.[clarification needed]

By this time, Neruda enjoyed worldwide fame as a poet, and his books were being translated into virtually all the major languages of the world.[39] He vigorously denounced the United States during the Cuban Missile Crisis and later in the decade repeatedly condemned the U.S. for its involvement in the Vietnam War. But being one of the most prestigious and outspoken left-wing intellectuals alive, he also attracted opposition from ideological opponents. The Congress for Cultural Freedom, an anti-communist organization covertly established and funded by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, adopted Neruda as one of its primary targets and launched a campaign to undermine his reputation, reviving the old claim that he had been an accomplice in the attack on Leon Trotsky in Mexico City in 1940.[59] The campaign became more intense when it became known that Neruda was a candidate for the 1964 Nobel Prize, which was eventually awarded to Jean-Paul Sartre.[60] (who rejected it).

In 1966, Neruda was invited to attend an International PEN conference in New York City.[61] Officially, he was barred from entering the U.S. because he was a communist, but the conference organizer, playwright Arthur Miller, eventually prevailed upon the Johnson Administration to grant Neruda a visa.[61] Neruda gave readings to packed halls and even recorded some poems for the Library of Congress.[61] Miller later opined that Neruda's adherence to his communist ideals of the 1930s was a result of his protracted exclusion from "bourgeois society." Due to the presence of many Eastern Bloc writers, Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes later wrote that the PEN conference marked a "beginning of the end" of the Cold War.[61]

Upon Neruda's return to Chile, he stopped in Peru, where he gave readings to enthusiastic crowds in Lima and Arequipa and was received by President Fernando Belaúnde Terry.[61] However, this visit also prompted an unpleasant backlash; because the Peruvian government had come out against the government of Fidel Castro in Cuba, July 1966 saw more than 100 Cuban intellectuals retaliate against the poet by signing a letter that charged Neruda with colluding with the enemy, calling him an example of the "tepid, pro-Yankee revisionism" then prevalent in Latin America. The affair was particularly painful for Neruda because of his previous outspoken support for the Cuban revolution, and he never visited the island again, even after receiving an invitation in 1968.

After the death of Che Guevara in Bolivia in 1967, Neruda wrote several articles regretting the loss of a "great hero".[62] At the same time, he told his friend Aida Figueroa not to cry for Che but for Luis Emilio Recabarren, the father of the Chilean communist movement who preached a pacifist revolution over Che's violent ways.

Last years and death

[edit]

In 1970, Neruda was nominated as a candidate for the Chilean presidency but ended up giving his support to Salvador Allende, who later won the election and was inaugurated in 1970 as Chile's first democratically elected socialist head of state.[57][63] Shortly thereafter, Allende appointed Neruda the Chilean ambassador to France, lasting from 1970 to 1972; his final diplomatic posting. During his stint in Paris, Neruda helped to renegotiate the external debt of Chile, billions owed to European and American banks, but within months of his arrival in Paris, his health began to deteriorate.[57] Neruda returned to Chile two-and-a-half years later due to his failing health.

In 1971, Neruda was awarded the Nobel Prize,[57] a decision that did not come easily because some of the committee members had not forgotten Neruda's past praise of Stalinist dictatorship. But his Swedish translator, Artur Lundkvist, did his best to ensure the Chilean received the prize.[64] "A poet," Neruda stated in his Stockholm speech of acceptance of the Nobel Prize, "is at the same time a force for solidarity and for solitude."[65] The following year, Neruda was awarded the prestigious Golden Wreath Award at the Struga Poetry Evenings.[66]

As the coup d'état of 1973 unfolded, Neruda was diagnosed with prostate cancer. The military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet saw Neruda's hopes for Chile destroyed. Shortly thereafter, during a search of the house and grounds at Isla Negra by Chilean armed forces at which Neruda was reportedly present, the poet famously remarked: "Look around – there's only one thing of danger for you here – poetry."[67]

It was originally reported that, on the evening of 23 September 1973, at Santiago's Santa María Clinic, Neruda had died of heart failure.[68][69][70]

However, "(t)hat day, he was alone in the hospital where he had already spent five days. His health was declining, and he called his wife, Matilde Urrutia, so she could come immediately because they were giving him something, and he wasn't feeling good."[5] On 12 May 2011, the Mexican magazine Proceso published an interview with his former driver Manuel Araya Osorio in which he states that he was present when Neruda called his wife and warned that he believed Pinochet had ordered a doctor to kill him, and that he had just been given an injection in his stomach.[4] He died six-and-a-half hours later. Even reports from the pro-Pinochet El Mercurio newspaper[citation needed] the day after Neruda's death refer to an injection given immediately before Neruda's death. According to an official Chilean Interior Ministry report[citation needed] prepared in March 2015 for the court investigation into Neruda's death, "he was either given an injection or something orally" at the Santa María Clinic "which caused his death six-and-a-half hours later. The 1971 Nobel laureate was scheduled to fly to Mexico where he may have been planning to lead a government in exile that would denounce General Augusto Pinochet, who led the coup against Allende on September 11, according to his friends, researchers, and other political observers".[5] The funeral took place amidst a massive police presence, and mourners took advantage of the occasion to protest against the new regime, established just a couple of weeks before. Neruda's house was broken into, and his papers and books taken or destroyed.[57]

In 1974, his Memoirs appeared under the title I Confess I Have Lived, updated to the last days of the poet's life, and including a final segment describing the death of Salvador Allende during the storming of the Moneda Palace by General Pinochet and other generals – occurring only 12 days before Neruda died.[57] Matilde Urrutia subsequently compiled and edited for publication the memoirs and possibly his final poem "Right Comrade, It's the Hour of the Garden." These and other activities brought her into conflict with Pinochet's government, which continually sought to curtail Neruda's influence on the Chilean collective consciousness.[citation needed] Urrutia's own memoir, My Life with Pablo Neruda, was published posthumously in 1986.[71] Manuel Araya, his Communist Party-appointed chauffeur, published a book about Neruda's final days in 2012.[72]

Controversy

[edit]Rumored murder and exhumation

[edit]In June 2013, a Chilean judge ordered an investigation to be launched following suggestions that Neruda had been killed by the Pinochet regime due to his pro-Allende stance and political views. Neruda's driver, Manuel Araya, claimed that he had seen Neruda two days prior to his death and that doctors had administered poison as the poet was preparing to go into exile. Araya claimed that he was driving Neruda to buy medicine when he was suddenly stopped by military personnel who arrested him, hijacked the Fiat 125 he was driving, and took him to police headquarters where they tortured Araya. He found out Neruda had died after Santiago Archbishop Raúl Silva Henríquez informed him.[73][74][75] In December 2011, Chile's Communist Party asked Chilean Judge Mario Carroza to order the exhumation of the remains of the poet. Carroza had been conducting probes into hundreds of deaths allegedly connected to abuses of Pinochet's regime from 1973 to 1990.[72][76] Carroza's inquiry during 2011–12 uncovered enough evidence to order the exhumation in April 2013.[77] Eduardo Contreras, a Chilean lawyer who was leading the push for a full investigation, commented, "We have world-class labs from India, Switzerland, Germany, the US, Sweden; they have all offered to do the lab work for free." The Pablo Neruda Foundation fought the exhumation on the grounds that Araya's claims were unbelievable.[75]

In June 2013, a court order was issued to find the man who allegedly poisoned Neruda. Police were investigating Michael Townley, who was facing trial for the killings of General Carlos Prats (Buenos Aires, 1974) and ex-Chancellor Orlando Letelier (Washington, 1976).[78][79] The Chilean government suggested that the 2015 test showed it was "highly probable that a third party" was responsible for his death.[80]

Test results were released on 8 November 2013 of the seven-month investigation by a 15-member forensic team. Patricio Bustos, the head of Chile's medical legal service, stated, "No relevant chemical substances have been found that could be linked to Mr. Neruda's death" at the time.[81] However, Carroza said that he was waiting for the results of the last scientific tests conducted in May (2015), which found that Neruda was infected with the Staphylococcus aureus bacterium, which can be highly toxic and result in death if modified.[5]

A team of 16 international experts led by Spanish forensic specialist Aurelio Luna from the University of Murcia announced on 20 October 2017 that "from analysis of the data, we cannot accept that the poet had been in an imminent situation of death at the moment of entering the hospital" and that death from prostate cancer was not likely at the moment when he died. The team also discovered something in Neruda's remains that could possibly be a laboratory-cultivated bacterium. The results of their continuing analysis were expected in 2018.[82] His cause of death was, in fact, listed as a heart attack.[83] Scientists who exhumed Neruda's body in 2013 also supported claims that he was suffering from prostate cancer when he died.[6]

In 2023, a team from McMaster University and the University of Copenhagen confirmed the presence of the Clostridium botulinum bacteria in Neruda's bloodstream, although it is not clear if this contributed to his death.[84] McMaster researcher Debi Poinar noted that if Neruda had died of botulism, he would've suffered paralysis or septicemia, a serious blood infection.[84] The bacteria was found to have been mainly concentrated in one of Neruda's molars.[85]

Some scientists involved in the testing also spoke with Deutsche Welle to deny the family's claim that the testing confirmed he was poisoned;[86] despite at times being used as a biological weapon, the bacteria also has a long history of being present in food products such as fruit, vegetables, seafood and canned food and at times has been even used for medical treatment.[87][88][89] John Austin, who leads the Botulism Reference Service for Canada, also told Deutsche Welle that the mere presence of C. botulinum is not harmful to humans, and that it the harm that comes from it is the toxins it produces when it grows.[86] Austin further stated the bacteria in Neruda's mouth could've even expanded after he died, as it is common for bacteria to multiply in the body among people after they die.[86] Fabrizio Anniballi, another botulism expert who was not directly involved in the research on Neruda's remains, further noted it was too unlikely that the injection he was alleged to been given into belly gave him botulism, noting that it was also claimed he died a mere six hours it happened, which is not a feasible amount of time to trigger botulism.[86] Debi Poinar also acknowledged to Deutsche Welle that while some C. botulinum was found in Neruda's bones, it had yet to be discerned whether it was from the same source as that found in the molar.[86]

Feminist protests

[edit]In November 2018, the Cultural Committee of Chile's lower house voted in favor of renaming Santiago's main airport after Neruda. The decision sparked protests from feminist groups who highlighted a passage in Neruda's memoirs describing a sexual encounter, his description of which resembles rape, with a maid in 1929 in Ceylon (Sri Lanka).[90] Several feminist groups, bolstered by a growing #MeToo and anti-femicide movement, stated that Neruda should not be honored by his country, describing the passage as evidence of rape. Neruda remains a controversial figure for Chileans, and especially for Chilean feminists.[91]

Legacy

[edit]Neruda owned three houses in Chile; today, they are all open to the public as museums: La Chascona in Santiago, La Sebastiana in Valparaíso, and Casa de Isla Negra in Isla Negra, where he and Matilde Urrutia are buried. A bust of Neruda stands on the grounds of the Organization of American States building in Washington, D.C.[92]

In popular culture

[edit]Music

[edit]Chilean composer Sergio Ortega worked closely with Neruda in the musical play Fulgor y muerte de Joaquín Murieta (Splendor and death of Joaquín Murieta) in 1967. In 1998, Ortega expanded the piece into an opera, leaving Neruda's text intact.[93]

Numerous groups and individuals have set the poems by Neruda to music, including:

- Leon Schidlowsky: Caupolicán (1958), Carrera (1991), and Lautaro (2009), among others.[94]

- Michael Gielen: pentaphony Ein Tag tritt hervor (1960–63)[95]

- Samuel Barber: cantata The Lovers (1971).[96]

- Peter Schat: cantata Canto General (1974), dedicated to Salvador Allende.[97]

- Mikis Theodorakis: oratorio Canto General (1975).[98]

- Julia Stilman-Lasansky: Cantata No. 3 (1976)[99]

- Dan Welcher: Abeja Blanca for Mezzo-Soprano, English Horn, and Piano (1978), dedicated to Jan DeGaetani.[100]

- Los Jaivas: rock album Alturas de Macchu Picchu (1981)

- Sixpence None the Richer: song "Puedo escribir" (1997) on their self-titled album.

- Tobias Picker: vocal works Tres Sonetos de Amor (2000)[101] and Cuatro Sonetos de Amor (2014).[102]

- Luciana Souza: jazz album Neruda (2004), featuring the music of Federico Mompou.[103]

- Brazilian Girls: song "Me gusta cuando callas" (2005) on their self-titled album.

- Morten Lauridsen: choral song "Soneto de la noche" (2005) as part of the song cycle Nocturnes.[104]

- Peter Lieberson: Neruda Songs (2005) and Songs of Love and Sorrow (2010).[105]

- Ezequiel Viñao: song cycle Sonetos de amor (2012).[106]

- Marco Katz: song cycle Las Piedras del cielo (2012) for voice and piano.[107]

- Ute Lemper: album Forever (2013)

Literature

[edit]- The character of The Poet in Isabel Allende's debut novel The House of the Spirits (1982) is an allusion to Neruda.[108][109]

- Neruda's 1952 stay in a villa on the island of Capri was fictionalized in Chilean author Antonio Skarmeta's 1985 novel Ardiente paciencia.[110] The novel in turn served as the basis for the 1994 film Il Postino as well as the 2010 opera of the same name by Daniel Catán.

- In the 2007 novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Pakistani author Mohsin Hamid, a key time in the political radicalization of the protagonist – a young Pakistani intellectual – is his short stay in Chile, in the course of which he visits the preserved home of Pablo Neruda.

- In 2008, the writer Roberto Ampuero published a novel El caso Neruda, about his private eye Cayetano Brulé where Pablo Neruda is one of the protagonists.

- The Dreamer (2010) is a children's fictional biography of Neruda, written by Pam Muñoz Ryan and illustrated by Peter Sís. The text and illustrations are printed in Neruda's signature green ink.[111]

- Isabel Allende's 2019 novel, A Long Petal of the Sea, has numerous Chilean historical key figures in its narrative. Allende writes about the life of Neruda and his involvement in the transportation of numerous fugitives from the Franco regime to Chile.

Film

[edit]The biographical dramas Neruda (2016) and Alborada (2021)[112] center on Neruda's life. The Italian film Il Postino (1994) is a fictional work about a humble man who is hired to deliver mail by bicycle to just one recipient of the island Procida, Neruda, living there in exile.

The English film Truly, Madly, Deeply (1990), written and directed by Anthony Minghella, uses Neruda's poem "The Dead Woman" as a pivotal device in the plot when Nina (Juliet Stevenson) understands she must let go of her dead lover Jamie (Alan Rickman).

Other films referencing Neruda's works include Mindwalk (1990), Patch Adams (1998), Chemical Hearts (2020) and Happiness for Beginners (2023).

List of works

[edit]Original

[edit]- Crepusculario. Santiago, Ediciones Claridad, 1923.

- Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada. Santiago, Editorial Nascimento, 1924.

- Tentativa del hombre infinito. Santiago, Editorial Nascimento, 1926.

- Anillos. Santiago, Editorial Nascimento, 1926. (Prosa poética de Pablo Neruda y Tomás Lago.)

- El hondero entusiasta. Santiago, Empresa Letras, 1933.

- El habitante y su esperanza. Novela. Santiago, Editorial Nascimento, 1926.

- Residencia en la tierra (1925–1931). Madrid, Ediciones del Árbol, 1935.

- España en el corazón. Himno a las glorias del pueblo en la guerra: (1936–1937). Santiago, Ediciones Ercilla, 1937.

- Nuevo canto de amor a Stalingrado. México, 1943.

- Tercera residencia (1935–1945). Buenos Aires, Losada, 1947.

- Alturas de Macchu Picchu. Ediciones de Libreria Neira, Santiago de Chile, 1948.

- Canto general. México, Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, 1950.

- Los versos del capitán. 1952.

- Todo el amor. Santiago, Editorial Nascimento, 1953.

- Las uvas y el viento. Santiago, Editorial Nascimento, 1954.

- Odas elementales. Buenos Aires, Editorial Losada, 1954.

- Nuevas odas elementales. Buenos Aires, Editorial Losada, 1955.[113]

- Tercer libro de las odas. Buenos Aires, Losada, 1957.

- Estravagario. Buenos Aires, Editorial Losada, 1958.

- Navegaciones y regresos. Buenos Aires, Editorial Losada, 1959.

- Oda al Gato, original poem in Navegaciones y regresos book.

- Cien sonetos de amor. Santiago, Editorial Universitaria, 1959.

- Canción de gesta. La Habana, Imprenta Nacional de Cuba, 1960.

- Poesías: Las piedras de Chile. Buenos Aires, Editorial Losada, 1960. Las Piedras de Pablo Neruda

- Cantos ceremoniales. Buenos Aires, Losada, 1961.

- Memorial de Isla Negra. Buenos Aires, Losada, 1964. 5 volúmenes.

- Diez Odas para diez grabados de Roser Bru. Barcelona, El Laberint, 1965.

- Arte de pájaros. Santiago, Ediciones Sociedad de Amigos del Arte Contemporáneo, 1966.

- Fulgor y muerte de Joaquín Murieta. Santiago, Zig-Zag, 1967. La obra fue escrita con la intención de servir de libreto para una ópera de Sergio Ortega.

- La Barcarola. Buenos Aires, Losada, 1967.

- Las manos del día. Buenos Aires, Losada, 1968.

- Comiendo en Hungría. Editorial Lumen, Barcelona, 1969. (En co-autoría con Miguel Ángel Asturias)

- Fin del mundo. Santiago, Edición de la Sociedad de Arte Contemporáneo, 1969. Con Ilustraciones de Mario Carreño, Nemesio Antúnez, Pedro Millar, María Martner, Julio Escámez y Oswaldo Guayasamín.

- Aún. Editorial Nascimento, Santiago, 1969.

- Maremoto. Santiago, Sociedad de Arte Contemporáneo, 1970. Con Xilografías a color de Carin Oldfelt Hjertonsson.

- La espada encendida. Buenos Aires, Losada, 1970.

- Las piedras del cielo. Editorial Losada, Buenos Aires, 1970.

- Discurso de Estocolmo. Alpignano, Italia, A. Tallone, 1972.

- Geografía infructuosa. Buenos Aires, Editorial Losada, 1972.

- La rosa separada. Éditions du Dragon, París, 1972 con grabados de Enrique Zañartu.

- Incitación al Nixonicidio y alabanza de la revolución chilena. Santiago, Empresa Editora Nacional Quimantú, Santiago, 1973.

English translations

[edit]- The Heights of Macchu Picchu (bilingual edition) (Jonathan Cape Ltd London; Farrar, Straus, Giroux New York 1966, translated by Nathaniel Tarn, preface by Robert Pring-Mill)(broadcast by the BBC Third Programme 1966)

- Selected Poems: A Bilingual Edition, translated by Nathaniel Tarn. (Jonathan Cape Ltd London 1970)

- The Captain's Verses (bilingual edition) (New Directions, 1972) (translated by Donald D. Walsh)

- New Poems (1968-1970) (bilingual edition) (Grove Press, 1972) (translated by Ben Belitt)

- Residence on Earth (bilingual edition) (New Directions, 1973) (translated by Donald D. Walsh)

- Extravagaria (bilingual edition) (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974) (translated by Alastair Reid)

- Selected Poems.(translated by Nathaniel Tarn: Penguin Books, London 1975)

- Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair (bilingual edition) (Jonathan Cape Ltd London; Penguin Books, 1976 translated by William O'Daly)

- Still Another Day (Copper Canyon Press, 1984, 2005) (translated by William O'Daly)

- The Separate Rose (Copper Canyon Press, 1985) (translated by William O'Daly)

- 100 Love Sonnets (bilingual edition) (University of Texas Press, 1986) (translated by Stephen Tapscott)

- Winter Garden (Copper Canyon Press, 1987, 2002) (translated by James Nolan)

- The Sea and the Bells (Copper Canyon Press, 1988, 2002) (translated by William O'Daly)

- The Yellow Heart (Copper Canyon Press, 1990, 2002) (translated by William O'Daly)

- Stones of the Sky (Copper Canyon Press, 1990, 2002) (translated by William O'Daly)

- Selected Odes of Pablo Neruda (University of California Press, 1990) (translated by Margaret Sayers Peden)

- Canto General (University of California Press, 1991) (translated by Jack Schmitt)

- The Book of Questions (Copper Canyon Press, 1991, 2001) (translated by William O'Daly)

- The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, an anthology of 600 of Neruda's poems, some with Spanish originals, drawing on the work of 36 translators. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux Inc, New York, 2003, 2005).[114]

- 100 Love Sonnets (bilingual edition) (Exile Editions, 2004, new edition 2016) (translated and with an afterword by Gustavo Escobedo; Introduction by Rosemary Sullivan; Reflections on reading Neruda by George Elliott Clarke, Beatriz Hausner and A. F. Moritz)

- On the Blue Shore of Silence: Poems of the Sea (Rayo HarperCollins, 2004) (translated by Alastair Reid, epilogue Antonio Skármeta)

- The Essential Neruda: Selected Poems (City Lights, 2004) (translated by Robert Hass, Jack Hirschman, Mark Eisner, Forrest Gander, Stephen Mitchell, Stephen Kessler, and John Felstiner. Preface by Lawrence Ferlinghetti)

- Intimacies: Poems of Love (HarperCollins, 2008) (translated by Alastair Reid)

- The Hands of the Day (Copper Canyon Press, 2008) (translated by William O'Daly)

- All The Odes (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2013) (various translators, prominently Margaret Sayers Peden)

- Then Come Back: The Lost Neruda (Copper Canyon Press, 2016) (translated by Forrest Gander)[115]

- Venture of the Infinite Man (City Lights, 2017) (translated by Jessica Powell; introduction by Mark Eisner)

- Book of Twilight (Copper Canyon Press, 2018) (translated by William O'Daly)

- Grapes and the Wind (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing, 2019) (translated by Michael Straus)

References

[edit]- ^ "Neruda". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1971".

- ^ Wyman, Eva Goldschmidt; Zurita, Magdalena Fuentes (2002). The Poets and the General: Chile's Voices of Dissent under Augusto Pinochet 1973–1989 (1st ed.). Santiago de Chile: LOM Ediciones. p. 18. ISBN 978-956-282-491-0. In Spanish and English.

- ^ a b "Neruda fue asesinado". Proceso (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Chile believes it "highly likely" that poet Neruda was murdered in 1973". El País. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ a b Shoichet, Catherine E. (13 November 2013). "Tests find no proof Pablo Neruda was poisoned; some still skeptical". CNN. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (8 November 2013). "Poet Pablo Neruda Was Not Poisoned, Officials in Chile Say". NPR.

- ^ Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza (1 March 1983). The Fragrance of Guava: Conversations with Gabriel García Márquez. Verso. p. 49. ISBN 9780860910657. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Campos, Bárbara (12 July 2019). "115 años del nacimiento de Pablo Neruda". pauta (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Tarn (1975) p. 13

- ^ "Biografía". Fundación Pablo Neruda (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Documento sin título". www.emol.com. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Neruda, Pablo (1975). Selected poems of Pablo Neruda. The Penguin Poets. Translated by Kerrigan, Anthony. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-14-042185-9.

- ^ Adam Feinstein (2005). Pablo Neruda: A Passion For Life. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-58234-594-9. Despite their political differences, Pablo had far more in common with Bombal than with Maruca.

- ^ a b c d e Tarn (1975) p. 14

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 19

- ^ Pablo Neruda. Biography.com.

- ^ Neruda, Pablo (1976). Vyznávám se, že jsem žil. Paměti (in Czech). Prague: Svoboda.

- ^ Sedlák, Marek (30 May 2007). "Jak se Basoalto stal Nerudou" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Bustos, Ernesto (10 May 2015). "El origen del nombre de Neruda (Segunda parte)". Narrativa Breve (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Robertson, Enrique (2002). "Pablo Neruda, el enigma inaugural". letras.mysite.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Pablo Neruda | Chilean poet". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ a b Tarn (1975) p. 15

- ^ Eisner, Mark (1 May 2018). Neruda: el llamado del poeta. HarperCollins Espanol. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4185-9767-2.

- ^ "Marietje Antonia Reyes-Hagenaar". geni_family_tree. 5 March 1900. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Mark Eisner: Pablo Neruda – The Poet's Calling [The Biography of a Poet], New York, Ecco/Harper Collins 2018; page 190

- ^ a b c d Tarn (1975) p. 16

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 109

- ^ "Neruda's Ghosts". 18 September 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ "The Tragic Story Of Pablo Neruda's Abandoned Daughter". 8 March 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ Sánchez, Matilde (26 February 2018). "La historia de cómo Pablo Neruda abandonó a su hija hidrocefálica". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Rego, Paco (20 February 2018). "La hija madrileña a la que Pablo Neruda abandonó y llamaba 'vampiresa de 3 kilos'". El Mundo (in Spanish). Unidad Editorial Información General, S.L.U. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Vantroyen, Jean-Claude (25 April 2019). "Malva, une victime de l'oubli paternel ressuscitée par Hagar Peeters - Le premier roman empathique de la poète néerlandaise donne une voix à la fille répudiée de l'immense poète, penseur et activiste chilien Pablo Neruda". Le Monde. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2012). The Spanish Civil War (50th Anniversary ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-141-01161-5.

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 434

- ^ Mark Eisner: Pablo Neruda – The Poet's Calling [The Biography of a Poet], New York, Ecco/Harper Collins 2018; page 306

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 141

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 145

- ^ a b c d e f Tarn (1975), p. 17

- ^ Feinstein (2005), p. 340

- ^ Feinstein (2005), p. 244

- ^ a b c Feinstein (2005) pp. 312–313

- ^ Roman, Joe. (1993) Octavio Paz Chelsea House Publishers ISBN 978-0-7910-1249-9

- ^ Paz, Octavio (1991) On Poets and Others. Arcade. ISBN 978-1-55970-139-6 p. 127

- ^ Neruda, La vida del poeta: Cronología, 1944–1953, Fundación Neruda, University of Chile. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- ^ "Alberto Acereda – El otro Pablo Neruda – Libros". Libros.libertaddigital.com. 1 January 1990. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 263

- ^ Shull (2009) p. 69

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 181

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 199

- ^ http://www.cubadebate.cu/opinion/2009/01/22/cronica-de-un-testigo-sobre-la-visita-de-fidel-a-venezuela-hace-50-anos/ [bare URL]

- ^ Burgin (1968) p. 95.

- ^ Burgin (1968) p. 96.

- ^ a b Feinstein (2005) pp. 236–7

- ^ a b Feinstein (2005) p. 290

- ^ "Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon: Selected Poems of Pablo Neruda – Eagle Harbor Book Co". Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tarn (1975) p. 22

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 278

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 487

- ^ Feinstein (2005) pp. 334–5

- ^ a b c d e Feinstein (2005) pp. 341–5

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 326

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 367

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 333

- ^ Pablo Neruda (1994). Late and posthumous poems, 1968–1974. Grove Press.

- ^ "Pablo Neruda". Струшки вечери на поезијата. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Feinstein (2005) p. 413

- ^ "Pablo Neruda, Nobel Poet, Dies in a Chilean Hospital", The New York Times, 24 September 1973.

- ^ Neruda and Vallejo: Selected Poems, Robert Bly, ed.; Beacon Press, Boston, 1993, p. xii.

- ^ Earth-Shattering Poems, Liz Rosenberg, ed.; Henry Holt, New York, 1998, p. 105.

- ^ Urrutia, Matilde; translated by Alexandria Giardino (2004). My Life with Pablo Neruda. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5009-7.

- ^ a b Newman, Lucia (21 May 2012). "Was Pablo Neruda murdered?". Aljazeera.

- ^ "The last days of Pablo Neruda, as told by his driver and secretary". 10 November 2015.

- ^ "Chile judge orders Pablo Neruda death probe". BBC News. 2 June 2011.

- ^ a b Franklin, Jonathan (7 April 2013). "Pablo Neruda's grave to be exhumed over Pinochet regime murder claims". The Guardian.

- ^ "Pablo Neruda death probe urged in Chile". CBC News. 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Unravelling the mystery of Pablo Neruda's death". BBC. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ "Revelan que un ex agente de la CIA envenenó a Neruda". INFOnews. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Washington Post, 2 June 2013, "Chilean judge issues order to investigate poet Neruda's alleged killer"

- ^ "Pablo Neruda: experts say official cause of death 'does not reflect reality'". the Guardian. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Forensic tests show no poison in remains of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda" 8 November 2013 Washington Post.

- ^ "Researchers raise doubts over cause of Chilean poet Neruda's death". Reuters. 21 October 2017. Reuters.

- ^ Guardian Staff (6 December 2011). "Pass notes No 3,091: Pablo Neruda". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b Beattie, Samantha (16 February 2023). "Poisonous bacteria was in Chilean poet Pablo Neruda's bloodstream when he died, McMaster scientists find". CBC News. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Donovan, Michelle (15 February 2023). "Was Pablo Neruda poisoned? New analysis shows covert assassination remains a possibility in Chilean poet-politician's mysterious death". McMaster University. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Roth, Clare (20 February 2023). "Pablo Neruda's death: Why the science is inconclusive". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Sterba, James P. (28 April 1982). "THE History Of Botulism". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Jabbari, Bahman (28 November 2016). "History of Botulinum Toxin Treatment in Movement Disorders". Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements. 6: 394. doi:10.7916/D81836S1. PMC 5133258. PMID 27917308.

- ^ Finlay, Fisher F. "G653(P) The history of botox". British Society for the History of Paediatrics and Child Health. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Neruda, Pablo. Memoirs. Translated by Hardie St. Martin, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1977.

- ^ "Poet, hero, rapist – outrage over Chilean plan to rename airport after Neruda". TheGuardian.com. 23 November 2018. Guardian

- ^ "OAS and Chile Rededicate Bust of Gabriela Mistral at the Organization’s Headquarters in Washington, DC," 31 January 2014, OAS website. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ "Fulgor y Muerte de Joaquín Murieta (1967) - Memoria Chilena, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile". www.memoriachilena.gob.cl. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Albertson, Dan; Hannah, Ron. "Leon Schidlowsky – The Living Composers Project". www.composers21.com. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Siohan, Robert (17 March 1967). "'UN DIA SOBRESALE', de Gielen". Le Monde.fr (in French). Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Plevka, Helen (2020). "Musical, Lyrical, Universal? Neruda's Amor into Barber's Lovers". Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal. 53 (1): 125–142. ISSN 0027-1276. JSTOR 26909742.

- ^ "Peter Schat". The Independent. 21 February 2003. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "La fascinante historia de la amistad entre Mikis Theodorakis y Pablo Neruda que llevó al compositor griego a musicalizar el poemario "Canto General"". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International Encyclopedia of Women Composers. Books & Music (USA). ISBN 978-0-9617485-0-0.

- ^ "Abeja Blanca for Mezzo-Soprano, English Horn, and Piano, Dan Welcher". LA Phil. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Cariaga, Daniel (4 October 2002). "The Pacific Symphony Embraces a Challenge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "NIEUWE CD UITGAVEN" (in Dutch). Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Heckman, Don (18 April 2004). "Brazilian, Chilean expand boundaries of Latin jazz". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Morten Lauridsen – Nocturnes". The Classical Source. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Shea, Andrea (30 March 2010). "Lieberson's 'Songs Of Love And Sorrow' And New Life". NPR. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Ezequiel Viñao". The New Yorker. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Bienvenido al sitio web de la Fundación Pablo Neruda – Fundación Pablo Neruda". Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ Antoni, Robert (1988). "Parody or Piracy: The Relationship of "The House of the Spirits" to "One Hundred Years of Solitude"". Latin American Literary Review. 16 (32): 16–28. ISSN 0047-4134. JSTOR 20119492.

- ^ Foreman, P. Gabrielle (1992). "Past-on Stories: History and the Magically Real, Morrison and Allende on Call". Feminist Studies. 18 (2): 369–388. doi:10.2307/3178235. hdl:2027/spo.0499697.0018.209. ISSN 0046-3663. JSTOR 3178235.

- ^ Skármeta, Antonio (1994). Burning Patience. Graywolf Press. ISBN 978-1-55597-197-7.

- ^ Hommel, Maggie (2010). "The Dreamer (review)". Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. 63 (11): 498–499. doi:10.1353/bcc.0.1916. ISSN 1558-6766.

- ^ "Asoka's poetic film on Pablo Neruda goes to Tokyo".

- ^ Segura, Tonatiuh (15 August 2019). "Los mejores poemas de Pablo Neruda". Randomeo. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ "Pablo Neruda". Poetry Foundation. 10 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Alter, Alexandra (24 July 2015). "Rediscovered Pablo Neruda Poems to Be Published". ArtsBeat. The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Feinstein, Adam (2004). Pablo Neruda: A Passion for Life, Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-58234-410-2

- Neruda, Pablo (1977). Memoirs (translation of Confieso que he vivido: Memorias), translated by Hardie St. Martin, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1977. (1991 edition: ISBN 978-0-374-20660-4)

- Shull, Jodie (January 2009). Pablo Neruda: Passion, Poetry, Politics. Enslow. ISBN 978-0-7660-2966-8. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- Tarn, Nathaniel, Ed (1975). Pablo Neruda: Selected Poems. Penguin.

- Burgin, Richard (1968). Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges, Holt, Rinehart, & Winston

- Consuelo Hernández (2009). "El Antiorientalismo en Pablo Neruda;" Voces y perspectivas en la poesia latinoamericanana del siglo XX. Madrid: Visor 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Pablo Neruda: The Poet's Calling [The Biography of a Poet], by Mark Eisner. New York, Ecco/HarperCollins 2018

- Translating Neruda: The Way to Macchu Picchu John Felstiner 1980

- The poetry of Pablo Neruda. Costa, René de., 1979

- Pablo Neruda: Memoirs (Confieso que he vivido: Memorias) / tr. St. Martin, Hardie, 1977

External links

[edit]- Profile at the Poetry Foundation

- Profile at Poets.org with poems and articles

- Pablo Neruda on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, 13 December 1971 Towards the Splendid City

- Guibert, Rita (Spring 1971). "Pablo Neruda, The Art of Poetry No. 14". The Paris Review. Spring 1971 (51).

- NPR Morning Edition on Neruda's Centennial 12 July 2004 (audio 4 mins)

- "Pablo Neruda's 'Poems of the Sea'" 5 April 2004 (Audio, 8 mins)

- "The ecstasist: Pablo Neruda and his passions". The New Yorker. 8 September 2003

- Documentary-in-progress on Neruda, funded by Latino Public Broadcasting site features interviews from Isabel Allende and others, bilingual poems

- Poems of Pablo Neruda

- "What We Can Learn From Neruda's Poetry of Resistance". The Paris Review. 16 March 2018 by Mark Eisner

- Pablo Neruda recorded at the Library of Congress for the Hispanic Division's audio literary archive on June 20, 1966

- Pablo Neruda

- 1904 births

- 1973 deaths

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers

- 20th-century Chilean poets

- 20th-century Chilean male writers

- Ambassadors of Chile to France

- People from Linares Province

- Chilean atheists

- Chilean male poets

- Chilean communists

- Chilean diplomats

- Chilean expatriates in Argentina

- Chilean expatriates in Spain

- Chilean expatriates in Mexico

- Chilean Marxists

- Chilean Nobel laureates

- Chilean surrealist writers

- Communist poets

- Communist Party of Chile politicians

- Deaths from prostate cancer in Chile

- Death conspiracy theories

- Members of the Senate of Chile

- National Prize for Literature (Chile) winners

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- People of the Spanish Civil War

- Politicians from Santiago

- Stalin Peace Prize recipients

- Surrealist poets

- Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath laureates

- Sonneteers