Alphabet City, Manhattan

Alphabet City | |

|---|---|

Avenue C was designated Loisaida Avenue in recognition of the neighborhood's Puerto Rican heritage | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40°43′34″N 73°58′44″W / 40.726°N 73.979°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Manhattan |

| Community District | Manhattan 3[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.2 km2 (0.47 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 45,317 |

| • Density | 37,000/km2 (96,000/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • White | 41.5% |

| • Hispanic | 30.6% |

| • Asian | 14.3% |

| • Black | 9.3% |

| • Other | 4.4% |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $63,717 |

| ZIP Code | 10009 |

| Area codes | 212, 332, 646, and 917 |

| Part of a series on |

| Race and ethnicity in New York City |

|---|

Alphabet City is a neighborhood located within the East Village in the New York City borough of Manhattan. Its name comes from Avenues A, B, C, and D, the only avenues in Manhattan to have single-letter names. It is bounded by Houston Street to the south and 14th Street to the north, and extends roughly from Avenue A to the East River.[4] Some famous landmarks include Tompkins Square Park, the Nuyorican Poets Cafe and the Charlie Parker Residence.

The neighborhood has a long history, serving as a cultural center and ethnic enclave for Manhattan's German, Polish, Hispanic, and immigrants of Jewish descent. However, there is much dispute over the borders of the Lower East Side, Alphabet City, and East Village. Historically, Manhattan's Lower East Side was 14th Street at the northern end, bound on the east by East River and on the west by First Avenue; today, that same area is Alphabet City. The area's German presence in the early 20th century, in decline, virtually ended after the General Slocum disaster in 1904.

Alphabet City is part of Manhattan Community District 3 and its primary ZIP Code is 10009.[1] It is patrolled by the 9th Precinct of the New York City Police Department.

Etymology

[edit]The Commissioners' Plan of 1811, which laid out the grid scheme of Manhattan above Houston Street, designated 16 north-south "avenues." Twelve numbered avenues were to run continuously to Harlem, while four lettered ones—A, B, C and D—appeared intermittently wherever the island widened east of First Avenue.[5] The plan called for stretches of Avenue A and Avenue B north of midtown, all of which have been renamed. In 1943, Avenue A went as far north as 25th Street, Avenue B ended at 21st Street and Avenue C reached 18th Street.[6] Stuyvesant Town, a post–World War II private residential development, blotted out the rest of A and B above 14th Street (sparing only a few blocks of Avenue C). What remained of 1811's lettered avenues came to be called, by some, Alphabet City.

There is disagreement about the earliest uses of the name. It is often characterized as a marketing invention of realtors and other gentrifiers who arrived in the 1980s.[7][8] However, sociologist Christopher Mele connects the term to the arts scene of the late 1970s which in turn attracted real estate investors.[9] As such, argues Mele, Alphabet City and its many variants—Alphaville,[10] Alphabetland,[11] etc.—were "playful" but also "concealed the area's rampant physical and social decline and downplayed the area’s Latino identity."[9] Pete Hamill, a longtime New York City journalist, cites darker origins. NYPD officers, he claims, referred to the most degraded areas east of Avenue B as Alphabet City in the 1950s.[12]

Whatever its origins, the name began to appear in print around 1980 with all three associations—crime, art, and gentrification. A December 1980 article in the Daily News reported on the eastward flow of gentrification:

Ave A. is still the DMZ. While the one side has been the East Village since the days of hippie heaven, the other side has become known, by Spanish-speaking locals, as Loisaida, and, by hand-rubbing realtors, as Alphabet City.[13]

The Official Preppy Handbook, published in October 1980, caricatured a subgroup of preppies as "connoisseurs of punk ... who spend their weekends in alphabet city (Avenues A, B, C, and D) on the Lower East Side."[14] Similarly, a November 1984 article in The New York Times reported "Younger artists ... are moving downtown to an area variously referred to as Alphabetland, Alphabetville, or Alphabet City (Avenues A, B, C and so forth on the Lower East Side of Manhattan)."[15]

The term appeared in March 1983 in the New York Daily News regarding anti-drug raids in the area.[16] It also appeared in The New York Times in an April 1984 editorial by Mayor Ed Koch justifying recent police operations:

The neighborhood, known as Alphabet City because of its lettered avenues that run easterly from First Avenue to the river, has for years been occupied by a stubbornly persistent plague of street dealers in narcotics whose flagrantly open drug dealing has destroyed the community life of the neighborhood.[17]

In common, Mele notes, the early uses shared the "mystique of 'living on the edge.'"[18] As early as 1989, however, a Newsday article suggested the mood, even among newcomers, had changed:

Residents call the area east of Avenue A between Houston and 14th Streets "the neighborhood," "The East Village," "The Lower East Side" or its Spanglish version, "Loisaida." That's because calling it "Alphabet City" brings too many memories of the days when outsiders began coming to Avenues A, B, C and D for the galleries, the clubs and the drugs.[19]

Several local nickname sets associated with the ABCD denotation have included Adventurous, Brave, Crazy and Dead and, more recently by writer George Pendle, "Affluent, Bourgeois, Comfortable, Decent".[20]

History

[edit]Before urbanization

[edit]

Prior to development, most of present-day Alphabet City was a salt marsh, regularly flooded by the tides of the East River (technically an estuary, not a river).[21][22] Marshes played a critical role in the food web and protected the coast. The Lenape Native Americans who inhabited Manhattan before European contact presided over similar ecosystems from New York Bay to Delaware Bay.[23] They tended to settle in forest clearings.[24] In summer, however, they foraged shellfish, gathered cordgrass for weaving, and otherwise exploited the wetlands.[25][26]

Dutch settlers brought a different model of land ownership and use.[27] In 1625, representatives of the Dutch West India Company set their sights on lower Manhattan, with plans for a fortified town at its tip served by farms above.[28] In 1626, they "purchased" the island from a local Lenape group and began parceling the land into boweries (from the Dutch for "farm").[29] The northern half of the Alphabet City area was part of Bowery Number 2. The southwest quarter was part of Bowery Number 3.[30] Both belonged initially to the company but were soon sold to individuals. By 1663, a year before surrendering the colony to England, Director General Peter Stuyvesant had acquired the relevant part of Number 2 and much of Number 3 from other settlers.[31] The company divided the southeast quarter of Alphabet City into small lots associated with larger parcels further away from the shore.[30] In this way, upland farmers gained access to the unique tidal ecosystem—"salt meadow" as they called it—and with it, "salt hay," a cordgrass species valued as fodder.[32] In his influential Description of New Netherland (1655), Adriaen van der Donck informed his fellow Dutchmen:

There [are] salt meadows; some so extensive that the eye cannot oversee the same. Those are good for pasturage and hay, although the same are overflowed by the spring tides, particularly near the seaboard. These meadows resemble the lows and outlands of the Netherlands. Most of them could be dyked and cultivated.[33]

The Dutch, then, were singularly attuned to the potential for land reclamation. During the city's first two centuries, however, large-scale landfill was limited to the more commercial southern end of the island, particularly wharfs at the mouth of the East River.[34] Stuyvesant and his heirs, with the help of slave labor, continued to occupy their farm as a country estate, cultivating it lightly and making few changes to the land.[35][36]

Development of the avenues

[edit]

After the Revolutionary War, with a surge in population and trade, the city was poised to grow northward. Around 1789, Peter Stuyvesant, great-grandson of the Director General by that name, came up with a plan for the area, mapping out streets to build and lots to sell.[37] In doing so, he was following the precedent of landowners to the south.[38] However, by this time, the city was laying out roads of its own and wanted to connect the whole.[39] The first proposal for a unified street system was the Mangin–Goerck Plan. Presented in 1799, it extended Stuyvesant's grid into the cove above Alphabet City, straightening the shoreline such that Alphabet City and the Lower East Side were no longer an isolated bulge.[40] When this plan succumbed to political squabbles and landowner demands, the city appealed to the state to dictate a design.[41] The result was the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, setting out the street grid of Manhattan above Houston Street.

"In general," the commissioners resolved, everything "should be rectangular."[42] However, the new roads were rotated relative to the existing ones just below Alphabet City. Moreover, the commissioners could do little to straighten the shoreline. They were limited by charter to reclaiming 400 feet beyond the low-water mark, much less than the Mangin-Goerck plan entailed.[43] First Avenue reflected this limit. It was drawn parallel to Fifth Avenue (called Middle Road in earlier designs[44]) as far east as possible while not straying too far into the water. Irregular bits of land protruded beyond First Avenue and, for these cases, the commissioners turned to lettered avenues. Avenues A and B appeared around Alphabet City, popped up again above midtown, and once more in Harlem (they were eventually renamed or eliminated above Alphabet City). Avenues C and D existed only in Alphabet City. Thus the neighborhood was misaligned with the old grid and relatively disconnected to the new one.

On the other hand, Alphabet City retained its long, arcing bank along the East River, just north of the ever-growing ports and shipyards that animated the city. The commissioners placed the avenues on the east side of the island closer together in anticipation of denser development there.[45] For Alphabet City proper, they envisioned a wholesale food market supplying the entire city. It would extend from 7th to 10th Street and from First Avenue to the river, with a canal up the middle. The commissioners wrote: "The place selected for this purpose is a salt marsh, and from that circumstance, of inferior price, though in regard to its destination, of greater value than other soil."[46]

Despite having sought a binding plan, the city requested many modifications from the state during execution, generally along lines demanded by property interests.[47] Given the marshy environs, Alphabet City landowners, mostly Stuyvesants, argued for an extra measure of deference and the city concurred:

It is stated in the memorial [of the landowners] and the fact is unquestionable that the extensive tract of sunken meadow land lying between North Street [now Houston Street] and Brandy mulah Point [Burnt Mill Point, near 12th Street] cannot be improved with any prospect of Benefit to the Owners unless upon the most Economical Scale of Expense and under all the Encouragements which can be offered by the Corporation Consistently with the public Interests.[48]

To this end, the proposed market place, like most of the public spaces in the plan, was returned to private hands. It was reduced to a sliver in 1815,[49] then scrapped altogether in 1824.[50][51] The city argued that the land was too remote to serve its intended purpose at the time and that holding onto it would deter development.[52] Urban historian Edward Spann lamented, "What was perhaps the most far-sighted feature of the Plan was the first to be completely eliminated."[53]

In the same act that abolished the market place, the state accommodated a landowner petition to narrow just the lettered avenues.[50] From the standard avenue width of 100 feet (30 m), Avenue A was reduced to 80 feet (24 m), Avenues B, C and D to 60 feet (18 m), the width of most cross-streets.[54] "Incapable of use as thoroughfares to and from the City," wrote the city council, "they cannot be considered as avenues in the proper Sense of the term." Instead, they should "correspond as far as possible with the Old Streets [below Houston] of which they will form the Continuation & be called by the Same names & be regulated by the Corporation as Streets."[52]

Weighing heavily in these decisions was the marsh itself and the water that drained—or failed to drain—through it. The debate about grading and draining Alphabet City's streets went round and round for over a decade, even as filling proceeded.[55][56][57][58] The standard design called for the land to slope down to the river uniformly throughout the watershed, which extended as far inland as Bowery. However, landowners, who would be assessed the cost of road construction, objected to the expense of so much landfill. In 1823, a newly created committee, with latitude to amend the 1811 plan, proposed to save money with a network of closed sewers, but these suffered a bad reputation from repeated clogging in older parts of the city.[59][60] Another proposal, from a new committee, echoed the former market place design, calling for open, ornamented canals on 6th, 9th and 14th Streets.[61][62] In 1832, as no amount of fill seemed to stem periodic flooding,[63] the city resolved on a simpler sewer system. In this design, the land would slope down to Avenue C from both east and west like a trough, and flow through a sewer to the river at 14th Street (Avenue C was widened to 80 feet for the purpose).[60] With this decided, roads and buildings went forward, though sewer construction itself would wait for decades. Archaeological excavations along Avenue C at 8th Street show that the site was incrementally raised 10–12 feet between 1820 and 1840, occupied from the 1840s (with the aid of a private cistern), and only drained by the proposed sewer line in 1867.[64]

Dry dock district

[edit]

The Alphabet City area initially developed along the riverfront, during the 1820s, as part of the city's expanding shipbuilding and repair industry. Shipyards tended to form tight clusters in close proximity to specialized workers, such as ship carpenters, and ancillary manufacturers, such as iron works.[65] They also required lots of cheap space. Hence, the city's growth forced the shipyards to migrate periodically to peripheral sites: above Dover Street around 1750, below Corlears Hook (some five blocks south of Houston Street) around 1800, then, beginning in the 1820s, the marshes of Alphabet City.[66][67] During the 1840s and 50s, the East River, from Corlears Hook to 13th Street, and inland as far as Avenue C, represented the greatest concentration of shipbuilding activity in the country.[68] After the Civil War, land and labor costs, along with the switch from wood to more massive iron hulls, would push the industry off the island entirely.[69]

Shipyards first appeared along the southern end of the area's shoreline, roughly between Stanton and 3rd Street. This location was not only close to existing yards but also a relative high point. Indeed, it was called, rather confusingly, Manhattan Island, in reference to a knoll in the salt marsh, increasingly buried under wharfs.[a] Here, in 1806-7, Charles Brownne built the first commercial steamboat, Robert Fulton's Clermont, which helped establish the city's shipbuilding reputation.[72][73][b] Brothers Adam and Noah Brown (no relation to Charles) and Henry Eckford took over the spot[72][73] and, by 1819, extended the wharf along Lewis Street, east of the new grid plan, to 5th Street.[75] The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 called for a wholesale food market between 7th and 10th Street, but local landowners put a stop to this, clearing the way for more of the same. In 1825, a well-capitalized group of shipowners and builders formed the New York Dry Dock Company to upgrade the city's repair facilities.[76][77] They bought a chunk of waterfront recently sold off by Stuyvesants, running from 6th to 13th Street, and built an elaborate campus around 10th Street including Dry Dock Bank, Dry Dock Street (present-day Szold Place), and novel marine railways to elevate ships for repair.[78][79] Hence, the neighborhood as a whole was often called Dry Dock.[80][c]

In 1828, an observer wrote, "No place on this island has the destroying hand of man done more to alter the face of nature... Hills of great magnitude have been entirely levelled, or cut down, and used to fill up docks and wharves."[86] By the early 1840s, the shipyards formed a solid line along the riverfront,[87] jutting out several hundred feet from the former low-water mark of the marsh. Shipbuilders included Smith & Dimon (4th to 5th Street), William H. Webb (5th to 7th Street), Jacob A. Westervelt (7th to 8th Street) and William H. Brown (11th to 12th Street).[88][89][90] Alongside them were sparmakers, who built masts for the booming clipper trade, as well as iron works, which manufactured steam engines. Morgan Iron Works (9th to 10th Street) and Novelty Iron Works (12th to 14th Street) soon became the area's largest employers.[91] Novelty had about 1200 workers at its peak in the 1850s, and was regarded as a marvel of engineering and operations.[92][93]

As shipyards filled the riverfront, housing popped up nearby. In many cases, shipbuilders themselves played the role of developer. Noah Brown, for example, built a boardinghouse for apprentices south of Houston[94][95] and invested in large plots to the north.[96][97] Beginning around 1830, the Ficketts, another shipbuilding clan, built numerous three-story brick houses along Avenue D as well as cross streets west to Avenues C.[d] They occupied some themselves and rented lesser variants to skilled laborers.[102] By the early 1840s, shipyard owners dotted the neighborhood,[103] and the majority of the city's ship carpenters lived in a narrow strip of blocks along Avenue D and Lewis Street, a stone's throw from the wharfs.[104]

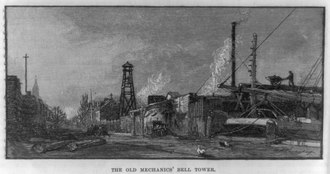

Throughout this period, the industry was dominated by in-migrants drawn to the booming shipyards from surrounding countryside and boatbuilding regions across New England.[105][106] They shared a traditional production model in which artisans progressed from apprentices to journeymen to masters, all while living and working side by side. Sean Wilentz, who documented the sweatshop proclivities of antebellum New York City, points to shipbuilding as the rare industry where tradition persisted and kept wages, skill and respect generally high.[107] He and others also credit shipyard workers with pioneering the reduction of work hours in the United States. A "Mechanics' Bell" hung for decades along the Alphabet City riverfront to enforce the ten-hour day that journeymen secured around 1834.[e] Labor reformer George McNeill likened it to a "'Liberty Bell' ... for the sons of toil."[111]

19th century

[edit]The Commissioners' Plan and resulting street grid was the catalyst for the northward expansion of the city,[112] and for a short period, the portion of the Lower East Side that is now Alphabet City was one of the wealthiest residential neighborhoods in the city.[113] Following the grading of the streets, development of rowhouses came to the East Side and NoHo by the early 1830s.[112] In 1833, Thomas E. Davis and Arthur Bronson bought the entire block of 10th Street from Avenue A to Avenue B. The block was located adjacent to Tompkins Square Park, located between 7th and 10th Streets from Avenue A to Avenue B, designated the same year.[114] Though the park was not in the original Commissioners' Plan of 1811, part of the land from 7th to 10th Streets east of First Avenue had been set aside for a marketplace that was ultimately never built.[115] Rowhouses of 2.5 to 3 stories were built on the side streets by such developers as Elisha Peck and Anson Green Phelps; Ephraim H. Wentworth; and Christopher S. Hubbard and Henry H. Casey.[116] Following the rapid growth of the neighborhood, Manhattan's 17th ward was split from the 11th ward in 1837. The former covered the area from Avenue B to the Bowery, while the latter covered the area from Avenue B to the East River.[117]

By the middle of the 19th century, many of the wealthy had continued to move further northward to the Upper West Side and the Upper East Side.[118]: 10 Some wealthy families remained, and one observer noted in the 1880s that these families "look[ed] down with disdain upon the parvenus of Fifth avenue."[119] In general, though, the wealthy population of the neighborhood started to decline as many moved northward. Immigrants from modern-day Ireland, Germany, and Austria moved into the neighborhood.[117]

The population of Manhattan's 17th ward, which included the western part of the modern Alphabet City, doubled from 18,000 people in 1840 to over 43,000 in 1850, and nearly doubled yet again to 73,000 persons in 1860, becoming the city's most highly populated ward at that time.[117][120]: 29, 32 As a result of the Panic of 1837, the city had experienced less construction in the previous years, and so there was a dearth of units available for immigrants, resulting in the subdivision of many houses in lower Manhattan.[117][121] Another solution was brand-new "tenant houses", or tenements, within the East Side.[118]: 14–15 Clusters of these buildings were constructed by the Astor family and Stephen Whitney.[122] The developers rarely involved themselves with the daily operations of the tenements, instead subcontracting landlords (many of them immigrants or their children) to run each building.[123] Numerous tenements were erected, typically with footprints of 25 by 25 feet (7.6 by 7.6 m), before regulatory legislation was passed in the 1860s.[122] To address concerns about unsafe and unsanitary conditions, a second set of laws was passed in 1879, requiring each room to have windows, resulting in the creation of air shafts between each building. Subsequent tenements built to the law's specifications were referred to as Old Law Tenements.[124][125] Reform movements, such as the one started by Jacob Riis's 1890 book How the Other Half Lives, continued to attempt to alleviate the problems of the area through settlement houses, such as the Henry Street Settlement, and other welfare and service agencies.[126]: 769–770

Because most of the new immigrants were German speakers, modern Alphabet City, East Village and the Lower East Side collectively became known as "Little Germany" (German: Kleindeutschland).[120]: 29 [127][128][129] The neighborhood had the third largest urban population of Germans outside of Vienna and Berlin. It was America's first foreign language neighborhood; hundreds of political, social, sports and recreational clubs were set up during this period.[127] Numerous churches were built in the neighborhood, of which many are still extant.[124] In addition, Little Germany also had its own library on Second Avenue in nearby East Village,[128] now the New York Public Library's Ottendorfer branch.[130] However, the community started to decline after the sinking of the General Slocum on June 15, 1904, in which over a thousand German-Americans died.[128][131]

The Germans who moved out of the area were replaced by immigrants of many different nationalities.[132] This included groups of Italians and Eastern European Jews, as well as Greeks, Hungarians, Poles, Romanians, Russians, Slovaks and Ukrainians, each of whom settled in relatively homogeneous enclaves.[126]: 769–770 In How the Other Half Lives, Riis wrote that "a map of the city, colored to designate nationalities, would show more stripes than on the skin of a zebra, and more colors than any rainbow."[125]: 20 One of the first groups to populate the former Little Germany were Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews, who first settled south of Houston Street before moving northward.[133] The Roman Catholic Poles as well as the Protestant Hungarians would also have a significant impact in the East Side, erecting houses of worship next to each other along 7th Street at the turn of the 20th century.[134] By the 1890s, tenements were being designed in the ornate Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival styles, though tenements built in the later part of the decade were built in the Renaissance Revival style.[135] At the time, the area was increasingly being identified as part of the Lower East Side.[136]

20th century

[edit]

The New York State Tenement House Act of 1901 drastically changed the regulations to which buildings in the East Side had to conform.[138] Simultaneously, the Yiddish Theatre District or "Yiddish Rialto" developed within the East Side, centered around Second Avenue. It contained many theaters and other forms of entertainment for the Jewish immigrants of the city.[139][140] By World War I, the district's theaters hosted as many as 20 to 30 shows a night.[140] After World War II, Yiddish theater became less popular,[141] and by the mid-1950s few theaters were still extant in the District.[142]

The city built First Houses on the south side of East 3rd Street between First Avenue and Avenue A, and on the west side of Avenue A between East 2nd and East 3rd Streets in 1935–1936, the first such public housing project in the United States.[126]: 769–770 [143]: 1 The Polish enclave in the East Village persisted, though numerous other immigrant groups had moved out, and their former churches were sold and became Orthodox cathedrals.[144] Latin American immigrants started to move to the East Side, settling in the eastern part of the neighborhood and creating an enclave that later came to be known as Loisaida.[145][146][147]

The East Side's population started to decline at the start of the Great Depression in the 1930s and the implementation of the Immigration Act of 1924, and the expansion of the New York City Subway into the outer boroughs.[148] Many old tenements, deemed to be "blighted" and unnecessary, were destroyed in the middle of the 20th century.[149] The Village View Houses on First Avenue between East 2nd and 6th Streets were opened in 1964,[150] partially on the site of the old St. Nicholas Kirche.[137]

Until the mid-20th century, the area was simply the northern part of the Lower East Side, with a similar culture of immigrant, working-class life. In the 1950s and 1960s, the migration of Beatniks into the East Village attracted hippies, musicians, writers, and artists who had been priced out of the rapidly gentrifying Greenwich Village.[150][151]: 254 Among the first displaced Greenwich Villagers to stray as far east as Alphabet City was poet Allen Ginsberg, who moved to 206 East 7th Street in 1951. His apartment served as a "nerve center" for writers such as William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso.[151]: 258 Further change came in 1955 when the Third Avenue elevated railway above the Bowery and Third Avenue was removed.[150][152] This in turn made the East Side more attractive to potential residents, and by 1960, The New York Times said that "this area is gradually becoming recognized as an extension of Greenwich Village ... thereby extending New York’s Bohemia from river to river".[150][153] The area became a center of the counterculture in New York, and was the birthplace and historical home of many artistic movements, including punk rock[154] and the Nuyorican literary movement.[155]

By the 1970s and 1980s, the city in general was in decline and nearing bankruptcy, especially after the 1975 New York City fiscal crisis.[145] Residential buildings in Alphabet City and the East Village suffered from high levels of neglect, as property owners did not properly maintain their buildings.[156] The city purchased many of these buildings, but was also unable to maintain them due to a lack of funds.[145] In spite of the deterioration of the area's structures, its music and arts scenes were doing well. By the 1970s, gay dance halls and punk rock clubs had started to open in the neighborhood.[157] These included the Pyramid Club, which opened in 1979 at 101 Avenue A; it hosted musical acts such as Nirvana and Red Hot Chili Peppers, as well as drag performers such as RuPaul and Ann Magnuson.[157]

Gentrification

[edit]

Alphabet City was one of many neighborhoods in New York to experience gentrification in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Multiple factors resulted in lower crime rates and higher rents in Manhattan in general, and Alphabet City in particular. Avenues A through D became distinctly less bohemian in the 21st century than they had been in earlier decades.[158] In the 1970s, rents were extremely low and the neighborhood was considered one of the least desirable places in Manhattan to live in.[159] However, as early as 1983, the Times reported that because of the influx of artists, many longtime establishments and immigrants were being forced to leave the area due to rising rents.[160] By the following year, young professionals constituted a large portion of the neighborhood's demographics.[159] Even so, crime remained prevalent and there were often drug deals being held openly in Tompkins Square Park.[161]

Tensions over gentrification contributed to the 1988 Tompkins Square Park riot, which occurred following opposition to a proposed curfew that had targeted the park's homeless. The aftermath of the riot slowed gentrification somewhat, as real estate prices declined.[162] However, by the end of the 20th century, real estate prices had resumed their rapid rise. About half of Alphabet City's stores had opened within the decade since the riot, while vacancy rates in that period had dropped from 20% to 3%, indicating that many of the longtime merchants had been pushed out.[163]

The Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space opened on Avenue C in the building known as C-Squat in 2012. An archive of urban activism, the museum explores the history of grassroots movements in the East Village and offers guided walking tours of community gardens, squats, and sites of social change.[164]

Political representation

[edit]Politically, Alphabet City is in New York's 7th and 12th congressional districts.[165][166] It is also in the New York State Senate's 27th and 28th districts,[167][168] the New York State Assembly's 65th and 74th districts,[169][170] and the New York City Council's 1st and 2nd districts.[171]

Architecture

[edit]Historic buildings

[edit]Local community groups such as the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP) are working to gain individual and district landmark designations for Alphabet City to preserve and protect the architectural and cultural identity of the neighborhood.[172] In early 2011, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) proposed a small district along the block of 10th Street that lies north of Tompkins Square Park.[173] The East 10th Street Historic District was designated by the LPC in January 2012.[174][175]

Several notable buildings are designated as individual landmarks. These include:

| Image | Name | Address | Year(s) built | Designation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Charlie Parker Residence | 151 Avenue B between 9th and 10th Streets | 1849 | National Register of Historic Places (1994), New York City Landmark (1999)[176] |

|

Children's Aid Society's Tompkins Square Lodging House for Boys and Industrial School aka Eleventh Ward Lodging House (former) | 295 East 8th Street at Avenue B | 1886 | New York City Landmark (2000)[177] |

|

Christodora House | 143 Avenue B at 9th Street | 1928 | National Register of Historic Places (1986)[178] |

|

Congregation Beth Hamedrash Hagadol Anshe Ungarin (former) | 242 East 7th Street between Avenues C and D | 1908 | New York City Landmark (2008)[179] |

|

Eleventh Street Methodist Episcopal Chapel (former) | 543-547 East 11th Street between Avenues A and B | 1867–1868 | New York City Landmark (2010)[180] |

|

First Houses | East 3rd Street and Avenue A | 1935–1936 | New York City Landmark (1974)[181] |

|

Free Public Baths of the City of New York (former) | 538 East 11th Street between Avenues A and B | 1904–1905 | New York City Landmark (2008)[182] |

|

Public National Bank of New York Building | 106 Avenue C at 7th Street | 1923 | New York City Landmark (2008)[183] |

|

Public School 64 (former) | 350 East 10th Street between Avenues B and C | 1904–1906 | New York City Landmark (2006)[184] |

|

St. Nicholas of Myra Church | 288 East 10th Street at Avenue A | 1882–3 | New York City Landmark (2008)[185] |

|

Wheatsworth Bakery Building | 444 East 10th Street between Avenues C and D | 1927–1928 | New York City Landmark (2008)[186] |

Other structures

[edit]Other buildings of note include "Political Row", a block of stately rowhouses on East 7th Street between Avenues C and D, where political leaders of every kind lived in the 19th century; the landmarked Wheatsworth Bakery building on East 10th Street near Avenue D; and next to it, 143-145 Avenue D, a surviving vestige of the Dry Dock District, which once filled the East River waterfront with bustling industry.

Alphabet City has a large number of surviving early 19th century houses connected to the maritime history of the neighborhood, which also are the first houses ever to be built on what had been farmland. Despite efforts by the GVSHP to preserve these houses, the LPC has not done so.[187] An 1835 rowhouse at 316 East 3rd Street was demolished in 2012 for the construction of a 33-unit rental called "The Robyn".[188] In 2010, GVSHP and the East Village Community Coalition asked the LPC to consider for landmark designation 326 and 328 East 4th Street, two Greek Revival rowhouses dating from 1837–41, which over the years housed merchants affiliated with the shipyards, a synagogue, and most recently an art collective called the Uranian Phalanstery. However, the LPC has not granted these rowhouses landmark status.[189] The LPC also declined to add 264 East 7th Street (the former home of illustrator Felicia Bond) and four neighboring rowhouses to the East Village/Lower East Side Historic District.[190]

In 2008, nearly the entire Alphabet City area was "downzoned" as part of an effort led by local community groups including GVSHP, the local community board, and local elected officials.[191] In most parts of Alphabet City, the rezoning requires that new development occur in harmony with the low-rise character of the area.[192]

Loisaida

[edit]Loisaida /ˌloʊ.iːˈsaɪdə/ is a term derived from the Spanish (and especially Nuyorican) pronunciation of "Lower East Side". Originally coined by poet/activist Bittman "Bimbo" Rivas in his 1974 poem "Loisaida", it now refers to Avenue C in Alphabet City, whose population has largely been Hispanic (mainly Nuyorican) since the 1960s.

Since the 1940s the demography of the neighborhood has changed markedly several times: the addition of the large labor-backed Stuyvesant Town–Peter Cooper Village after World War II at the northern end added a lower-middle to middle-class element to the area, which contributed to the eventual gentrification of the area in the 21st century; the construction of large government housing projects south and east of those and the growing Latino population transformed a large swath of the neighborhood into a Latin one until the late 1990s, when low rents outweighed high crime rates and large numbers of artists and students moved to the area. Manhattan's growing Chinatown then expanded into the southern portions of the Lower East Side, but Hispanics are still concentrated in Alphabet City. With crime rates down, the area surrounding Alphabet City, the East Village, and the Lower East Side, is quickly becoming gentrified; the borders of the Lower East Side differ from its historical ones in that Houston Street is now considered the northern edge, and the area north of that between Houston Street and 14th Street is considered Alphabet City. But, because the Alphabet City term is largely a relic of a high-crime era, English-speaking residents refer to Alphabet City as part of the East Village, while Spanish-speaking residents continue to refer to Alphabet City as Loisaida.

Police and crime

[edit]Alphabet City is patrolled by the 9th Precinct of the NYPD, located at 321 East 5th Street.[193] The 9th Precinct ranked 58th safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010.[194]

The 9th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 78.3% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct reported 0 murders, 40 rapes, 85 robberies, 149 felony assaults, 161 burglaries, 835 grand larcenies, and 32 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[195]

Fire safety

[edit]

Alphabet City is served by two New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[196]

- Ladder Co. 3/Battalion 6 – 103 East 13th Street[197]

- Engine Co. 28/Ladder Co. 11 – 222 East 2nd Street[198]

Post offices and ZIP Code

[edit]Alphabet City is located within the ZIP Code 10009.[199] The United States Postal Service operates two post offices near Alphabet City:

- Peter Stuyvesant Station – 335 East 14th Street[200]

- Tompkins Square Station – 244 East 3rd Street[201]

Notable residents

[edit]- Louis Abolafia (1941-1995) — artist, social activist, folk figure, and hippie candidate for President of the United States

- Joaquín Badajoz (born 1972) — poet, writer

- David Byrne, (born 1952) — musician, artist

- Cro-Mags - hardcore punk band

- Rosario Dawson (born 1979) — Cuban/Puerto Rican American actress

- Bobby Driscoll (1937-1968) — actor

- Eden and John's East River String Band - musicians who sometimes record and perform with cartoonist / musician Robert Crumb

- Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997) — poet, 206 E. 7th Street[202]

- Luis Guzman (born 1956) — Puerto Rican actor

- Jonathan Larson (1960-1996) — composer and playwright, resident during the 80s & 90s

- Leftöver Crack (formed 1998) — punk rock band

- John Leguizamo (born 1964) — Hispanic actor, stand-up comedian, filmmaker, playwright

- Madonna (born 1958) — singer[203]

- Charlie Parker (1920–1955) — jazz musician lived at 151 Avenue B between East 9th and East 10th Streets[204]

- Geraldo Rivera (born 1943) — television personality, resident during the late 60s - early 70s[205]

- Kiki Smith (born 1954) — artist

- John Spacely (died 1993) — musician, actor, and nightlife personality

- The Strokes (formed 1998) — rock band

- William H. Webb (1816-1899) — shipbuilder and philanthropist

- Bruce Willis — actor, resident during the early 1980s

In popular culture

[edit]Novels and poetry

- Henry Roth's novel Call It Sleep (1934) takes place in Alphabet City, with the novel's main character, David and his family, living there.

- Allen Ginsberg wrote many poems relating to the streets of his neighborhood in Alphabet City.

- David Price's novel Alphabet City (1983) tells the story of a man who leaves London to explore his homosexuality in the "wilderness of Avenues A, B, C and D."[206]

- Jerome Charyn's novel War Cries Over Avenue C (1985) takes place in Alphabet City.

- A fictional version of NYC's Alphabet City is explored in the Fallen Angels (1994) supplement to Kult.

- In his book Kitchen Confidential (2000), Anthony Bourdain says, "Hardly a decision was made without drugs. Cannabis, methaqualone, cocaine, LSD, psilocybin mushrooms soaked in honey and used to sweeten tea, secobarbital, tuinal, amphetamine, codeine and, increasingly, heroin, which we'd send a Spanish-speaking busboy over to Alphabet City to get."

- The protagonist of the novel The Russian Debutante's Handbook (2002) by Gary Shteyngart lives in Alphabet City in the mid-1990s.

- The Brendan Deneen horror/SF novel The Chrysalis (2018) begins in Alphabet City, but ends in a New Jersey suburb.

- The Adam Silvera and Becky Albertalli novel What If It's Us (2018) features the characters of Ben and Dylan who live in Alphabet City, respectively in Avenue B and Avenue C.

Comics

- In Marvel Comics, Alphabet City is home to District X, also known as Mutant Town, a ghetto primarily populated by mutants. The ghetto was identified as being inside Alphabet City in New X-Men #127. It was described in District X as having the 'highest unemployment rate in the USA, the highest rate of illiteracy and the highest severe overcrowding outside of Los Angeles'. (These figures would suggest a large population.) It was destroyed in X-Factor #34.

Photo books

- The photo and text book "Alphabet City" by Geoffrey Biddle[207] chronicles life in Alphabet City over the years 1977 to 1989.

- The photo book "Street Play" by Martha Cooper[208]

Places

- The punk house and independent gig venue C-Squat is called so because it sits on Avenue C, between 9th and 10th St. Bands and artists to emerge from the former squat include Leftöver Crack, Choking Victim, and Stza. Leftöver Crack makes several references to "9th and C", the approximate location of C-Squat in the song "Homeo Apathy" from the album Mediocre Generica.

Television

- The fictional 15th Precinct in the police drama NYPD Blue appears to cover Alphabet City, at least in part.

- In an appearance on The Tonight Show, writer P. J. O'Rourke said that when he lived in the neighborhood in the late 1960s, it was dangerous enough that he and his friends referred to Avenue A, Avenue B, and Avenue C as "Firebase Alpha", "Firebase Bravo", and "Firebase Charlie", respectively.

- In the episode "My First Kill" in Season 4 of Scrubs, J.D. (Zach Braff) wears a T-shirt with "Alphabet City, NYC" on it.

- The 1996 TV movie Mrs. Santa Claus is primarily set on Avenue A in Alphabet City in 1910.[209]

- In episode 6 of the 2009 police drama The Unusuals, "The Circle Line", an identity thief buys his ID from a dealer in Alphabet City.

- The episode "The Pugilist Break" of Forever is about a murder that takes place in Alphabet City; the episode highlights the history of the neighborhood and its current development and gentrification.

- In the episode "The Safety Dance" in "Season 2" of "The Carrie Diaries", Walt helps his boyfriend move into an apartment in Alphabet City.

- The Netflix series Russian Doll features several scenes in Tompkins Square Park and other locations in Alphabet City.

Films

- The Godfather Part II (1974) was filmed in part on 6th Street, between Avenues B and C. Proving what injection of money can do, they transformed a run-down block, with several empty buildings into a bustling immigrant neighborhood from 1917. Local residents were kept out of the filming area unless they happened to live on that block or joined on as extras.

- Alphabet City (1984), about a drug dealer's attempts to flee his life of crime, takes place in the neighborhood. Director Amos Poe had long covered the local punk scene. This was his first commercial film, starring Vincent Spano, Zohra Lampert and Jami Gertz.

- Mixed Blood (1985), directed by Paul Morrissey, was set and filmed in the pre-gentrification Alphabet City of the early 1980s.

- Batteries Not Included (1987), produced by Steven Spielberg, was shot on 8th Street between Avenues C and D. Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy play an elderly couple who resist gentrification-induced displacement with the aid of extraterrestrials.

- Flawless (1999), starring Philip Seymour Hoffman, Robert De Niro, and Wilson Jermaine Heredia, takes place in Alphabet City with all filming taking place there.

- Alphabet City is featured in the film 200 Cigarettes (1999).

- Downtown 81 (2000) was shot in the area around 1981, but only completed and released decades later. Characterized as "a road movie through Alphabet City,"[210] the film follows then-practically-unknown artist Jean-Michel Basquiat as he encounters an assortment of downtown musicians and scenesters.

- Alphabet City is mentioned in the monologue by Montgomery Brogan in the movie 25th Hour (2002).

- Character actor Josh Pais, who grew up in Alphabet City, conceived and directed a very personal documentary film, 7th Street Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine (2003). Shot over a period of ten years, it is both a "love letter" to the characters he saw everyday and a chronicle of the changes that took place in the neighborhood.

- Much of the independent film Supersize Me (2004) takes place in Alphabet City, near the residence of director Morgan Spurlock.

- The film Rent (2005), starring Rosario Dawson, Wilson Jermaine Heredia, Jesse L. Martin, Anthony Rapp, Adam Pascal, Idina Menzel, Taye Diggs, and Tracie Thoms, is an adaptation of the 1996 Broadway rock opera of the same name by Jonathan Larson (which itself is heavily based on Puccini's opera La Boheme) and set in Alphabet City on 11th Street and Avenue B, although many scenes were filmed in San Francisco. Unlike the stage musical, which is not set in a specific period of time, the film is clear that the story takes place between 1989 and 1990. Although this leads to occasional anachronisms in the story, the time period is explicitly mentioned to establish that the story takes place before the gentrification of Alphabet City.

- Some of the scenes in Ten Thousand Saints (2015) take place in Alphabet City, where one of the characters lives as a squatter.

Theatre

- The Broadway musical Rent takes place in Alphabet City. The characters live on East 11th Street and Avenue B. They hang out at such East Village locales as Life Cafe.

- In Tony Kushner's play, Angels in America (and the film adaptation of same), the character Louis makes a comment about "Alphabet Land", saying it's where the Jews lived when they first came to America, and "now, a hundred years later, the place to which their more seriously fucked-up grandchildren repair."

- The Tony Award-winning musical Avenue Q is set in a satirical Alphabet City. When the protagonist Princeton is introduced, he says, “I started at Avenue A but everything was out of my price range. But this neighborhood looks a lot cheaper! Hey look, a for rent sign!”

Music: Specific avenues

- Swans released a song titled "93 Ave B blues" after the address of Michael Gira's apartment.

- In Bongwater's "Folk Song" there is the repeated chorus "Hello death, goodbye Avenue A". Ann Magnuson, lead singer of Bongwater, lives on Avenue A.

- "Avenue A" is a song by The Dictators, from their 2001 CD, DFFD.

- The Pink Martini song "Hey Eugene" takes place "at a party on Avenue A."

- "Avenue A" is a song by Red Rider off their 1980 album, Don't Fight It.

- "The Belle of Avenue A" is a song by Ed Sanders.

- Escort refers to Avenue A in the song "Cabaret" on their album Animal Nature.

- Singer-songwriter Ryan Adams refers to Avenue A and Avenue B in his track "New York, New York".

- The 1978 classical salsa hit "Pedro Navaja", by Panamanian singer Rubén Blades, says at the end that the "lifeless bodies" of Pedro Barrios (Pedro Navaja) and Josefina Wilson were found on "lower Manhattan" "between Avenues A and B"...

- In Lou Reed's "Halloween Parade", from his highly acclaimed concept album New York (album), he mentions "the boys from Avenue B and the girls from Avenue D."

- "Avenue B" is a song by Gogol Bordello

- Avenue B is an album by Iggy Pop, who wrote the album while living at the Christodora House on Avenue B.

- "Avenue B" is a song by Mike Stern

- "Avenue C" is a Count Basie Band song, recorded by Barry Manilow in 1974 for his album Barry Manilow II.

- It is mentioned in Sunrise on Avenue C, James Maddock from the album Fragile.[211]

- "Venus of Avenue D" is a song by Mink DeVille.

- Avenue D is referred to in the Steely Dan song, "Daddy Don't Live In That New York City No More" off the 1975 album Katy Lied.

- Avenue D is referred to in the song "Capital City", sung by Tony Bennett in The Simpsons episode "Dancin' Homer".

Music: General

- Swans was formed on Avenue B.[212]

- Elliott Smith refers to "Alphabet City" in his song, "Alphabet Town", from his self-titled album.

- Alphabet City is an album by ABC.

- "Take A Walk With The Fleshtones" is a song by The Fleshtones on their album Beautiful Light (1994). The song devotes a verse to each Avenue.

- Alphabet City is mentioned in the song "Poster Girl" by the Backstreet Boys.

- In the song "New York City", written by Cub and popularized by They Might Be Giants, Alphabet City is mentioned in the chorus.

- The Clash mentions the neighborhood in the song "Straight to Hell": "From Alphabet City all the way a to z, dead, head"

- U2 refer to the neighborhood as "Alphaville" in their song "New York".

- In their song "Click Click Click Click" on the 2007 album The Broken String, Bishop Allen sing, "Sure I've got pictures of my own, of all the people and the places that I've known. Here's when I'm carryin' your suitcase, outside of Alphabet City".

- On Dan the Automator's "A Better Tomorrow", rapper Kool Keith quips that he is the "King of New York, running Alphabet City".

- "Alphabet City" is the name of the fifth track on the 2004 release, The Wall Against Our Back from the Columbus, Ohio band Two Cow Garage.

- Steve Earle's expressionistic "Down Here Below" (track 2 of Washington Square Serenade) cites: "And hey, whatever happened to Alphabet City? Ain’t no place left in this town that a poor boy can go"

- The dance hit "Sugar is Sweeter (Danny Saber Mix)" by CJ Bolland refers to the neighborhood with the lyrics, "Down in Alphabet City..."

- Mano Negra refers to Alphabet City in the song "El Jako", on the album King of Bongo (1991): "Avenue A: Here comes the day/Avenue B: Here goes the junky/Avenue C: There's no rescue/Death avenue is waiting for you" and "Avenue A: Here comes the day/Avenue B: Here goes the junky/Avenue C: It's an emergency/O.D.O.D. in Alphabet City".

- Joe Jackson's 1984 album Body and Soul features an instrumental track titled "Loisaida".

See also

[edit]- Community gardening

- Dos Blockos

- Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space

- Nuyorican Poets Cafe

- Riis Houses

- St. Brigid's Church

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Stokes, following De Voe, places the geographic feature itself above Houston: "Thos. F. De Voe, writing as late as 1862, said he remembered this piece of land, or knoll, between Houston and 3d Sts. Lewis St. ran about through the centre of it.— Market Book, 524. See also Poppleton’s Plan of 1817."[70] The Poppleton map shows a wharf from Stanton to the north side of 3rd Street labeled "Manhattan Island." Morrison describes the same wharf and dates it back to at least 1812.[71]

- ^ Maritime historian Charles Lawesson places Brownne's shipyard on the north side of Houston Street in the Alphabet City area proper.[74]

- ^ Several influential sources claim that the longer, more explicit variant, "Dry Dock District," was in fact the neighborhood's historical nickname. The New York City Parks Department has a plaque saying the "neighborhood ... was once known as the Dry Dock District."[81] In 2016, The New York Times wrote, "In the mid-19th century ... the area was known as the Dry Dock District."[82] However, there is simply no evidence. The earliest known use of the phrase is a Times article from 1886, well after the period. There, the paper used "district" (lowercase) in its specifically political sense, introducing a local senator as "the silver toned [sic] orator from the Dry Dock district,"[83] By contrast, the shorter variant, "Dry Dock," appeared in many contemporaneous maps, guidebooks, and transportation routes as a label for the dock and its immediate vicinity, e.g., "a jutting point on the East river, at present known as the Dry Dock."[84] By synecdoche, it also referred to broader areas, as in, "The extensive ship-yards in the north-east part of the city, in the region called Dry Dock, are very interesting places of resort."[85]

- ^ Environmental site assessments created for the city document the role of Samuel, Francis and other Ficketts on East 3rd,[98] 4th,[99] 7th, 8th,[100] and 9th[101] Streets.

- ^ Stories of the "Mechanics' Bell" differ in many particulars.[108][109][110] There is general agreement that the bell first hung in the Manhattan Island shipyards, roughly on Mangin between Stanton and Rivington, around 1831-4. Here it also served as the alarm for the wharf's volunteer fire company, called the Mechanics' Association, where "mechanic" was used in the historical sense of "artisan." Subsequently, a larger bell rang near the river on 5th Street from about 1844-1873, after which it led an on-again-off-again existence on 4th Street and was finally mothballed in 1897.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Manhattan census tracts 34, 22.02, 20, 24, 26.01, 26.02, 28, 30.02, 32". NYC Population FactFinder.

- ^ "Zip code 10009". Census Reporter.

- ^ Hughes, C.J. (September 6, 2017). "Living In: Alphabet City". The New York Times.

Stretching from Avenue A to the East River, and East 14th to East Houston Streets, Alphabet City is ...

- ^ Morris, Gouverneur; De Witt, Simeon; and Rutherford, John [sic] (March 1811) "Remarks Of The Commissioners For Laying Out Streets And Roads In The City Of New York, Under The Act Of April 3, 1807", Cornell University Library. Accessed June 27, 2016. "These are one hundred feet wide, and such of them as can be extended as far north as the village of Harlem are numbered (beginning with the most eastern, which passes from the west of Bellevue Hospital to the east of Harlem Church) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12. This last runs from the wharf at Manhattanville nearly along the shore of the Hudson river, in which it is finally lost, as appears by the map. The avenues to the eastward of number one are marked A, B, C, and D."

- ^ Stuyvesant Square, New York City Market Analysis, 1943. Accessed January 1, 2024.

- ^ Rowe, Peter G. (1997). Civic Realism. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262681056.

The term 'Alphabet City' only began to be used when gentrification made its first incursions into the neighborhood during the 1980s.

- ^ Chodorkoff, Dan (2014). The Anthropology of Utopia: Essays on Social Ecology and Community Development. New Compass Press.

Real estate developers ... rechristened the neighborhood 'alphabet city'.

- ^ a b Mele 2000, p. xi.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (1978-12-11). "Nietzsche in Alphaville". Village Voice. p. 33.

- ^ Hershkovits, David (September 1983). "Art in Alphabetland". ARTnews. pp. 88–92.

- ^ Hamill, Pete (2004). Downtown: My Manhattan. Little, Brown. p. 210. ISBN 9780316734516.

- ^ Hodenfield, Jan (December 4, 1980). "Gentrification comes to the lower East Side". Daily News.

- ^ Birnbach, Lisa (October 1980). The Official Preppy Handbook. Workman Publishing. p. 165. ISBN 9780894801402.

- ^ Freedman, Samuel (November 4, 1984). "Metropolis of the Mind". The New York Times. section 6, page 32, column 1. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ^ Davila, Albert. "See no pushover spillover", New York Daily News, March 6, 1984. Accessed November 1, 2023. "In late 1980 and 1981, similar raids in "Alphabet City" as the lower East Side is also known because of Avenues A, B, C and D produced an influx into Williamsburg of drug peddlers and buyers seeking 'safer ground' across the Williamsburg Bridge."

- ^ Koch, Ed (April 27, 1984). "Needed: Federal Anti-Drug Aid". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ^ Mele 2000, p. 236.

- ^ Sax, Irene (January 18, 1989). "Alphabet City: Beyond the drug dealers and burnt-out buildings is a neighborhood breathing new energy". Newsday.

- ^ Moss, Jeremiah. Vanishing New York:How a Great City Lost Its Soul. 2017, page 17

- ^ Bernard Ratzer (1776). Plan of the city of New York in North America: Surveyed in the years 1766 & 1767 (Map). Jefferys & Faden.

- ^ Hill & Waring 1897, p. 236.

- ^ Grumet, Robert S. (1989). The Lenapes. Chelsea House. p. 13. ISBN 9781555467128.

- ^ Grumet, Robert S. (2012). First Manhattans: A History of the Indians of Greater New York. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780806182964.

- ^ Homberger, Eric (2005) [1st pub. 1994]. The Historical Atlas of New York City. Henry Holt and Company. p. 16. ISBN 9780805078428.

- ^ McCully, Betsy (2007). City at the Water's Edge: A Natural History of New York. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rivergate Books, an imprint of Rutgers University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8135-3915-7. OCLC 137663737.

- ^ Van Zwieten, Adriana E. (2001). "A little land ... to sow some seeds": Real property, custom, and law in the community of New Amsterdam (Thesis). OCLC 52320808.

- ^ Abel, Jesper Nicolai (2017). Early Dutch presence in North America: The West India Company's relationship with its Dutch patroonship (PDF) (Thesis). p. 51.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, pp. 23–27.

- ^ a b Stokes 1928, PL. 84B-b.

- ^ Stokes 1928, pp. 142–144.

- ^ Greider 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Donck, Adriaen van der (1896) [1655]. Description of the New Netherlands. Translated by Johnson, Jeremiah. Directors of the Old South Work. p. 13.

- ^ Buttenwieser, Ann (1987). Manhattan, Water-Bound: Planning and Developing Manhattan's Waterfront from the Seventeenth Century to the Present. New York: New York University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8147-1093-7. OCLC 14691918.

- ^ Brazee & Most 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Blackmar, Elizabeth (1989). Manhattan for Rent, 1785-1850. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8014-9973-9. OCLC 18741278.

- ^ St. Mark's Historic District, Borough of Manhattan (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 14, 1969. p. 1.

- ^ Koeppel 2015, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Koeppel 2015, p. 25.

- ^ Koeppel 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784-1831. Vol. IV: May 20, 1805 to February 8, 1808. City of New York. 1917. p. 353. OCLC 576024162. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ Bridges 1811, p. 24.

- ^ Bridges 1811, p. 18.

- ^ Koeppel 2015, p. 22.

- ^ Spann 1988, p. 19.

- ^ Bridges 1811, p. 29.

- ^ Spann 1988, p. 27.

- ^ "In Common Council August 4th 1823", Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1784-1831, vol. XIII, M.B. Brown Print. & Binding Co., 1917, p. 201, OCLC 39817642

- ^ New York (State) 1855.

- ^ a b New York (State) 1855, An act making further alteration in the map or plan of the City of New York, Passed January 22, 1824.

- ^ Stokes, I. N. Phelps (1918). The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909. Vol. 3. New York: Robert H. Dodd. p. 959. OCLC 831811649.

- ^ a b Minutes of the Common Council XIII 1917, p. 201.

- ^ Spann 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Post, John J. (1882). Old streets, roads, lanes, piers and wharves of New York showing the former and present names, together with a list of alterations of streets, either by extending, widening, narrowing or closing. R.D. Cooke. p. 67. OCLC 1098350361.

- ^ Greider 2011, pp. 65-67.

- ^ Steinberg, Theodore (2014). Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 73-76. ISBN 9781476741246.

- ^ Spann 1988, pp. 25-26.

- ^ Stuyvesant Meadows 1832.

- ^ Stuyvesant Meadows 1832, "Report of the Commissioners to Establish a Permanent Regulation of the Streets and Avenues South of Thirty-Fourth Street, Dated 7th November 1825".

- ^ a b Greider 2011, pp. 66.

- ^ Stuyvesant Meadows 1832, "Report of Edward Doughty, City Surveyor, on Report of Commissioners, &c. in Common Council, Sep. 25th, 1826".

- ^ Hill & Waring 1897, p. 238.

- ^ Duffy, John (1968). A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625–1866. Russell Sage Foundation. p. 406.

- ^ Grossman, Joel W. (May 12, 1995). The Archaeology of Civil War Era Water Control Systems on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York (PDF) (Report). New York City Housing Authority. p. 24.

- ^ Pred 1966, pp. 327–329.

- ^ Pred 1966, p. 326.

- ^ Morrison 1909, pp. 9, 21.

- ^ Albion 1939, p. 287.

- ^ Pred 1966, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Stokes 1926, p. 1507.

- ^ Morrison 1909, p. 40.

- ^ a b Morrison 1909, p. 39.

- ^ a b McKay 1934, p. 38.

- ^ West, W. Wilson (2003). Monitor Madness: Union Ironclad Construction at New York City, 1862-1864 (Thesis). p. 20. OCLC 54985810.

- ^ John Randel Jr. (July 23, 1819). No. 2, showing North Street to 6th Street, from Avenue B to the East River, July 23, 1819 (Map).

- ^ Morrison 1909, p. 51: This company was brought into existence by the co-operation of the owners of the large sailing vessels, some of the owners of the Black Ball line of packets, to avoid the disadvantages to themselves of 'heaving down' their vessels when requiring repairs.

- ^ Sullivan, John L. (1827). A Description of the American Marine Rail-Way. Jesper Harding, printer. OCLC 316666851.

A few of the largest ship owners at New York ... associated to apply for an act of incorporation too build a dry dock.

- ^ Morrone, Francis (December 2018). A History of the East Village and Its Architecture (PDF) (Report). Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. pp. 8–11.

- ^ Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York. Vol. 6. 1838. p. 16.

The property that was then purchased extended from Sixth-street to Thirteenth-street, on the East river, and from the river back to Lewis Street and Avenue D, and from Tenth to Thirteenth-streets, about half the blocks about half way between Avenue D and Avenue C.

- ^ "Politicians' Row is Going". The New York Times. March 28, 1897.

This neighborhood was on the east side, and embraced the general lines of the old Eleventh Ward [which ran from Avenue B to the river and from Rivington to 14th Street], though its local designation to this day is 'Dry Dock.'

- ^ "Dry Dock Playground History". Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation.

- ^ Kaysen, Ronda (November 25, 2016). "An Uncertain Future for East Village Rowhouses". The New York Times.

- ^ "Rivals Hard at Work; Campbell realizing that Grady is a dangerous opponent". The New York Times. October 30, 1886.

- ^ Valentine, D.T. (1856). Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York. p. 474.

- ^ Ruggles, Edward (1846). Picture of New-York in 1846. Homans & Ellis. p. 76.

- ^ The picture of New-York, and Stranger's Guide to the Commercial Metropolis of the United States. A. T. Goodrich. 1828. p. 412.

- ^ Morrison 1909, p. 89.

- ^ Sheldon 1882a, p. 223.

- ^ "A Ramble among the Shipyards". The Evening Post. October 9, 1847.

- ^ Dripps, Matthew (1852). City of New York Extending Northward to Fiftieth St (Map).

- ^ Bishop, J. Leander (1868). A History of American Manufactures from 1608 to 1860. Vol. 3. E. Young. pp. 120-122.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, pp. 659–660.

- ^ Abbott, Jacob (December 1, 1850). "Novelty Iron Works; with Description of Marine Steam Engines, and their construction". Harper's New Monthly Magazine.

- ^ Sheldon 1882a, p. 234.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 442.

- ^ Morrison 1909, p. 49.

- ^ Stokes 1928, p. 120: "The other meadow of the Company, which belonged to Bouwery No. 8, vested in Eckford and Brown in 1815."

- ^ CITY/SCAPE: Cultural Resource Consultants (June 2000). Stage 1A Literature Review & Sensitivity Evaluation of Archaeological Potential: Block 372, Lot 26 (PDF) (Report).

- ^ Bergoffen, Celia J. (April 16, 2008). Lower East Side Rezoning: Phase 1A Archaeological Assessment Report, Part 1 Historical Background & Lot Histories (PDF) (Report). p. 48.

- ^ Mascia 2009.

- ^ Greenhouse Consultants Incorporated (March 2005). Archaeological and Historical Sensitivity Evaluation: 723 East Ninth Street Borough of Manhattan New York, New York (PDF) (Report).

- ^ Mascia 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Mascia 2009, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Pred 1966, p. 328.

- ^ Albion 1939, pp. 242–250.

- ^ Binder, Frederick (2019). All the Nations Under Heaven: Immigrants, Migrants, and the Making of New York. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-231-18984-2. OCLC 1049577021.

- ^ Wilentz, Sean (1984). Chants Democratic: New York City & the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788-1850. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 134-8. ISBN 978-0-19-503342-7. OCLC 9281934.

- ^ Morrison 1909, pp. 85-91.

- ^ Sheldon, George William (1882). The Story of the Volunteer Fire Department of the City of New York. Harper & brothers. pp. 156–7. OCLC 866246705.

- ^ Moynihan, Abram W. (1887). The Old Fifth Street School and the Association which Bears Its Name. A.W. Moynihan. pp. 91-93.

- ^ McNeill, George M. (1887). The Labor Movement: The Problem of To-Day. A.M. Bridgman & Co. p. 344. OCLC 57274104.

- ^ a b Brazee et al. 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (November 8, 1998). "Streetscapes / 19-25 St. Marks Place; The Eclectic Life of a Row of East Village Houses". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Stokes 1915, vol. 5, pp. 1726–1728.

- ^ Brazee & Most 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Brazee et al. 2012, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Dolkart, Andrew (2012). Biography of a Tenement House: An Architectural History of 97 Orchard Street. Biography of a Tenement House: An Architectural History of 97 Orchard Street. Center for American Places at Columbia College. ISBN 978-1-935195-29-0. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Lockwood 1972, p. 199.

- ^ a b Nadel, Stanley (1990). Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City, 1845-80. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01677-7.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 746.

- ^ a b Brazee et al. 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, pp. 448–449, 788.

- ^ a b Brazee et al. 2012, p. 21.

- ^ a b Riis, Jacob (1971). How the other half lives : studies among the tenements of New York. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-22012-3. OCLC 139827.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ a b Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 745.

- ^ a b c Haberstroh, Richard. "Kleindeutschland: Little Germany in the Lower East Side". LESPI-NY. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Susan Spano. "A Short Walking Tour of New York's Lower East Side". Smithsonian. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "About the Ottendorfer Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ O'Donnell, R. T. (2003). Ship ablaze: The tragedy of the steamboat General Slocum. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0905-4.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Sanders, R.; Gillon, E.V. (1979). The Lower East Side: A Guide to Its Jewish Past with 99 New Photographs. Dover books on New York City. Dover Publications. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-486-23871-5. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ a b "CHURCH BUILDING FACES DEMOLITION; 100-Year-Old St. Nicholas on the Lower East Side Is Sold to Company". The New York Times. January 27, 1960. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Rosenberg, Andrew; Dunford, Martin (2012). The Rough Guide to New York City. Penguin. ISBN 9781405390224. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- Let's Go, Inc (2006). Let's Go New York City 16th Edition. Macmillan. ISBN 9780312360870. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- Oscar Israelowitz (2004). Oscar Israelowitz's guide to Jewish New York City. Israelowitz Publishing. ISBN 9781878741622. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- Cofone, Annie (September 13, 2010). "Theater District; Strolling Back Into the Golden Age of Yiddish Theater". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Ronnie Caplane (November 28, 1997). "Yiddish music maven sees mamaloshen in mainstream". Jweekly. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ J. Katz (September 29, 2005). "O'Brien traces history of Yiddish theater". Campus Times. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ Lana Gersten (July 29, 2008). "Bruce Adler, 63, Star of Broadway and Second Avenue". Forward. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ "First Houses" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 12, 1974. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Brazee et al. 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa W. (May 17, 1987). "Will it be Loisaida of Alphabet city?; Two Visions Vie In the East Village". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ von Hassell, M. (1996). Homesteading in New York City, 1978-1993: The Divided Heart of Loisaida. Contemporary urban studies. Bergin & Garvey. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-89789-459-3. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Brazee et al. 2012, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Brazee et al. 2012, p. 35.

- ^ a b Miller, Terry (1990). Greenwich Village and how it got that way. Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-57322-8. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Katz, Ralph (May 13, 1955). "Last Train Rumbles On Third Ave. 'El'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ "'Village' Spills Across 3d Ave". The New York Times. February 7, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Schoemer, Karen (June 8, 1990). "In Rocking East Village, The Beat Never Stops". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Nieves, Santiago (May 13, 2005). "Another Nuyorican Icon Fades". New York Latino Journal. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved April 14, 2008..

- ^ Mele 2000, pp. 191–194.

- ^ a b Brazee et al. 2012, p. 38.

- ^ Shaw, Dad. "Rediscovering New York as It Used to Be", The New York Times, November 11, 2007. Accessed August 31, 2016.

- ^ a b "THE GENTRIFICATION OF THE EAST VILLAGE". The New York Times. September 2, 1984. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "NEW PROSPERITY BRINGS DISCORD TO THE EAST VILLAGE". The New York Times. December 19, 1983. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "IF YOU'RE THINKING OF LIVING IN; THE EAST VILLAGE". The New York Times. October 6, 1985. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "Prices Decline as Gentrification Ebbs". The New York Times. September 29, 1991. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "A New Spell for Alphabet City; Gentrification Led to the Unrest at Tompkins Square 10 Years Ago. Did the Protesters Win That Battle but Lose the War?". The New York Times. August 9, 1998. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Leland, John (8 December 2012). "East Village Shrine to Riots and Radicals". The New York Times.

- ^ Congressional District 7, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- Congressional District 12, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ New York City Congressional Districts, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ Senate District 27, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- Senate District 28, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ 2012 Senate District Maps: New York City, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed November 17, 2018.

- ^ Assembly District 65, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- Assembly District 74, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ 2012 Assembly District Maps: New York City, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed November 17, 2018.

- ^ Current City Council Districts for New York County, New York City. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ "East Village" Archived 2018-07-22 at the Wayback Machine on the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation website

- ^ "East Village Preservation" Archived 2018-07-22 at the Wayback Machine on the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation website

- ^ Berger, Joseph (January 19, 2012). "Designation of Historic District in East Village Won't Stop Project". City Room. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Brazee & Most 2012.

- ^ "Charlie Parker Residence" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 18, 1999.

- ^ "Children's Aid Society, Tompkins Square Lodging House for Boys and Industrial School" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 16, 2000. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "East 10th Street Historic District and Christodora House | Historic Districts Council's Six to Celebrate". 6tocelebrate.org. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- ^ "Congregation Beth Hamedrash Hagadol Anshe Ungarin" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 18, 2008.

- ^ "Eleventh Street Methodist Episcopal Chapel" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 14, 2010.

- ^ "First Houses" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 12, 1974. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "Free Public Baths of the City of New York" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 18, 2008.

- ^ "Public National Bank of New York Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 16, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "LPC Designation Report: Former P.S. 64" (PDF). NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ "Saint Nicholas of Myra Orthodox Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 16, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "Wheatsworth Bakery Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 16, 2008. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "Historic East Village House Rejected by Landmarks". Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- ^ "The Robyn is now fully exposed on East 3rd Street". EV Grieve blog.

- ^ "326 & 328 East 4th Street". Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 2020-09-27. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- ^ "An Uncertain Future for East Village Rowhouses". The New York Times. November 25, 2016. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Haughney, Christine (November 15, 2008). "High-Rises Are at Heart of Manhattan Zoning Battle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ^ "Keeping in Character: A Look at the Impacts of Recent Community-Initiated Rezonings in the East Village" (PDF). Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

- ^ "NYPD – 9th Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "East Village and Alphabet City – DNAinfo.com Crime and Safety Report". www.dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "9th Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Ladder Company 18/Battalion 4". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 9/Ladder Company 6". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "East Village, New York City-Manhattan, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Archived from the original on November 9, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Peter Stuyvesant". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Tompkins Square". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "The Allen Ginsberg Project - AllenGinsberg.org". The Allen Ginsberg Project. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Corman, Richard. "Photographer Richard Corman: I Shot Madonna", Out (magazine), March 10, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2016. "So I got this girl’s number and called. It was Madonna. At the time she was living in Alphabet City, and she suggested I go to her apartment and chat about what I wanted to do."

- ^ Gould, Jennifer. "All that jazz: Charlie Parker’s townhouse listed for $9.25M", New York Post, October 21, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2016. "The historic Charlie Parker residence in Alphabet City is now on the market for $9.25 million. The Gothic Revival-style, 23-foot-wide, landmarked brownstone at 151 Ave. B boasts original details — it was built around 1849 — including double-wood doors, a decorative relief beneath the cornice and a pointed archway with 'clustered colonettes,' according to the listing."

- ^ Rivera, Geraldo. "Geraldo Rivera: Call 911! Remembering The Mean Streets Of New York City", Fox News Latino, November 8, 2013. Accessed August 31, 2016. "Why do I tell this old story, almost quaint when you realize that aside from my mop the only weapons in the battle were the bottles used to crack open my head? Well, I could have told of my two decades in Alphabet City, like the four times my various apartments were burglarized or the numerous muggings, car vandalisms, robberies, murders or other scenes from Once Upon a Time in New York that I've seen close-up, but you get the idea."