Victor Harbor, South Australia

| Victor Harbor South Australia | |

|---|---|

Victor Harbor viewed from Bluff | |

| Coordinates | 35°33′0″S 138°37′0″E / 35.55000°S 138.61667°E |

| Population | 4,520 (SAL 2021)[1] |

| Established | 1863 |

| Postcode(s) | 5211[2] |

| Location | 82 km (51 mi) South of Adelaide city centre via |

| LGA(s) | City of Victor Harbor |

| Region | Fleurieu and Kangaroo Island[3] |

| State electorate(s) | Finniss[4] |

| Federal division(s) | Mayo[5] |

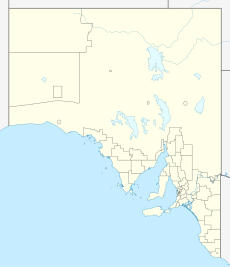

Victor Harbor is a town in the Australian state of South Australia located within the City of Victor Harbor on the south coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula, about 82 kilometres (51 mi) south of the state capital of Adelaide. The town is the largest population centre on the peninsula, with an economy based upon agriculture, fisheries, and tourism. It is a popular tourist destination, with the area's population greatly expanded during the summer holidays, usually by Adelaide locals looking to escape the summer heat.

The coast stretching for around 50 km (31 mi) from west of Victor Harbor along to Goolwa is often referred to as the South Coast, especially among surfers, as many of the beaches on this stretch are popular surfing spots.

It is a popular destination with South Australian high school graduates for their end of year celebrations, known colloquially as schoolies.

History[edit]

Victor Harbor lies in the traditional lands of the Ramindjeri clan of the Ngarrindjeri people.[citation needed]

Matthew Flinders in HMS Investigator visited the bay on 8 April 1802, while on the first circumnavigation of the continent, mapping the unsurveyed southern Australian coast from the west. He encountered Nicolas Baudin in Le Geographe near the Murray Mouth several kilometres to the east of the present day location of Victor Harbor.[citation needed] Baudin was surveying the coast from the east for Napoleonic France. Although their countries were at war, each captain was given documents by the other nation's government, stating that the ships were on scientific missions, and were therefore not to be regarded as ships of war.[citation needed] Together, the ships returned to the bay and sheltered, while the captains compared notes. Flinders named the bay Encounter Bay after the meeting.[citation needed]

In 1837, Captain Richard Crozier who was en route from Sydney to the Swan River Colony in command of HMS Victor,[6] anchored just off Granite Island and named the sheltered waters in the lee of the island 'Victor Harbor' after his ship.[7][full citation needed] At about the same time, two whaling stations were established, one at Rosetta Head, popularly known as "the Bluff", and the other near the point opposite Granite Island. Whale oil became South Australia's first export.[citation needed] From 1839, the whaling station was managed for a time by Captain John Hart, a later Premier of South Australia. The last whale was caught off Port Victor in 1872.[citation needed]

The town, the harbour, and spelling[edit]

The town of Port Victor was laid out on the shores of Victor Harbor in 1863 when the horse-drawn tramway from Goolwa was extended to the harbour.[citation needed]

The municipality of the town of Victor Harbor was proclaimed on 7 May 1914, with Oliver Alexander Baaner appointed the first mayor.[8] The township of Victor Harbor was proclaimed in 1914 with the spelling "Harbor".[9]

The harbour was proclaimed on 27 May 1915 under the Harbors Act 1913,[10] and its name established on 15 June 1921 as "Victor Harbor".[11] The name of the harbour was changed in June 1921 from Port Victor as a result of a near shipwreck blamed on confusion with Port Victoria on the Yorke Peninsula.[12]

The spelling of Victor Harbor, spelled without a u is a curiosity as harbour normally retains the "u" in Australian English. This spelling is found in several geographical names in South Australia, including Outer Harbor and Blanche Harbor. According to the State Library of South Australia, the lack of the "u" is not influenced by American spelling, but archaic English spelling.[13] The name is not consistently applied. The Victor Harbor Times used "Harbour" in its masthead from 1922 to 1978, before reverting to "Harbor".[14] The Victor Harbour railway station is spelt with the u.[15][13]

Entertainment[edit]

In 1923, two picture palaces opened in Victor Harbor: the Victor Theatre in Ocean Street on 24 November[16] (still operating today as the Victa Cinema; see below), and the Wonderview near the beachfront, opposite the Soldiers' Memorial Gardens, on 22 December 1923.[17]

On 26 December 1936, a one-off motor race meeting was held to the east of the town to commemorate the centenary of South Australia – the South Australian Centenary Grand Prix, often referred to as the 1937 Australian Grand Prix.[18] The circuit was made of public roads, measured 12.6 kilometres in length and featured two long straights, two short straights, and several corners, including the banked Nangawooka Hairpin.[19] The winners of the 240-mile Grand Prix, which was held as a handicap, were Les Murphy in an MG P-type, Tim Joshua in another P-type, and Bob Lea-Wright in a Terraplane Special.[18]

21st century[edit]

The beaches of Victor Harbor and nearby Port Elliot have been facing rising seas, and more has to be done to stop this.[20]

In November 2023, Victor Harbor mayor Moira Jenkins voiced strong opposition, citing risks to the environment, to a proposal for a $350 million marina in the town.[21] The project is promoted by local businessman Mark Taplin, who has stated that he wants to "enhance Victor Harbor."[22]

Governance[edit]

Victor Harbor was declared a city in 2000.[23]

As a local government area, the City of Victor Harbor includes the surrounding rural area and the contiguous township of Encounter Bay as well as the town of Victor Harbor itself. Its total area is 34,463 hectares. It shares boundaries with the District Council of Yankalilla and Alexandrina Council. The city is in the state electoral district of Finniss and the federal Division of Mayo.

Population[edit]

In the 2021 Australian census, the resident population in the town (locality) of Victor Harbor was 4,520, of whom 53% were female.[24] Over the summer holiday season the population almost triples.[25] The urban population for the built-up coastal area extending from Victor Harbor to Port Elliot and nearby Goolwa was 28,363.[26]

Attractions[edit]

Granite Island[edit]

A popular site for visitors is Granite Island, which is connected to the mainland by a short tram/pedestrian causeway. The tram service is provided by the Victor Harbor Horse Drawn Tram, one of the very few horse-drawn tram routes remaining in public transit service. Granite island is home to a large colony of little penguins which are a popular attraction on the island. These penguins shelter on the island during the night, departing in the morning to hunt for fish before returning at sunset. This colony of penguins has declined sharply, with only seven found in 2012. It is suspected that an increase in long-nosed fur seals in the area may be to blame; however, incidents such as those in 1998 where locals apparently kicked several of them to death have also contributed.[27] A December 2022 survey estimated 22 birds on the island,[28] with a different study putting the number at 26 that year. After 28 birds were counted in mid-2023, researchers were hopeful of a recovery in numbers.[29]

Cockle Train[edit]

The SteamRanger Heritage Railway runs train services, most notably The Cockle Train between Victor Harbor and Goolwa, along the Victor Harbor railway line.[30]

Whale-watching and visitor centre[edit]

Between June and September, whale spotting is a popular attraction. Southern right whales come to the nearby waters to calve and to mate. In 1990, Ian Milnes, a marine science teacher, established the original Whale Watch Centre, when there were few whales to be seen owing to the history of whaling from the 1830s until the 1980s, when it was banned. In 1990, there were seven sightings and 13 whales. The following winter, 40 whales were spotted. In 1994, the South Australian Whale Centre was established, with the support of the City of Victor Harbor and the South Australian Museum in a renovated goods shed at the terminus of the Cockle Train railway line.[31] The Railway Goods Shed was built in 1864, and used by early European settlers for storing goods and produce transported along the Murray River and then across the first Australian public railway, to be shipped around the world from Victor Harbor.[32] At one stage, the building housed the horse-drawn trams. After several renovations, including one in 2008, the centre hosts a number of interactive exhibits.[33] In December 2022, after more restoration of the goods shed, the building reopened as a combined Visitor Centre and SA Whale Centre, to be known as "Victor Harbor Visitor Centre", or "VC". The centre is open open 24/7 from 10am to 4pm apart from Christmas Day.[32]

Surfing[edit]

Victor Harbor is the centre of the surf zone stretching for around 50 km (31 mi) from west of Victor Harbor along to Goolwa, known as the "South Coast" to Adelaide and local surfers. Popular surf beaches in the area include Parsons, Waitpinga, Middleton, and Goolwa.[34][35] The Granite Island breakwater usually shields the town from waves. Victor Harbor offers numerous fishing opportunities, varying from offshore reefs for larger boat based anglers to excellent surf fishing on the beaches closer to the Murray Mouth.

Other attractions[edit]

The Urimbirra Wildlife Park is a local attraction with a considerable collection of native, and some domestic, animals.[36]

The Soldiers' Memorial Gardens on the Esplanade include a park and a war memorial within. Both were heritage-listed on the South Australian Heritage Register in 1985.[37]

Greenhills Adventure Park offered activities including waterslides, canoes, rock wall climbing, archery, mini golf, and go-karting; however this attraction has since closed down on 1 May 2016.[38]

Festivals and events[edit]

This town hosts a three-day schoolies festival in late November mainly for South Australian school leavers. Victor Harbor hosts the second largest[citation needed] schoolies festival in Australia after the Gold Coast, centring around official festival activities in Warland Reserve.

These events are managed by the official event organisers and not-for-profit charity, Encounter Youth, and are supported by the local council, SA Police, SA Ambulance and St Johns SA.[39]

The centre of the town is a dry zone (no alcohol) at night as well as during the Christmas Pageant and New Year's Eve.[40]

Another notable event is the Art Show run by the Rotary Club of Victor Harbor and exhibits of paintings are shown from all over Australia. The event is held in January, during the summer holidays, and the 40th Art Show was held in January 2019.[41] It has grown to become Australia's largest outdoor art exhibition, with more than 10,000 people attending over 9 nine days.[42]

Media[edit]

The main newspaper printed locally is the Times (1987–). The newspaper was originally published as The Victor Harbor Times and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot, with the first edition published on Friday 23 August 1912.[43] On 16 May 1930, the title was briefly altered to Times Victor Harbor and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot.[44] From 15 April 1932 until 31 December 1986 it was called Victor Harbor Times.[45]

Other historical publications included the short-lived South Coast News (4- 25 June 1965), printed by A.H. Ambrose,[46] and its "successor", South Coast Sports News (20 June – 4 July 1969), printed by The Ambrose Press.[47]

Picture palaces[edit]

Victor Theatre / Victa Cinema[edit]

The Victor Theatre was built on the site of Ocean Street Garage, owned by D.H. Griffin & Sons, designed by noted cinema architect Chris A. Smith. It opened under the control of Griffin Pictures on 24 November 1923, seating 700 people. It changed hands in October 1926, being sold to National Theatres (aka National Pictures[48]). After National Theatres went into liquidation in January 1928, its lease[49] was taken over by Ozone Theatres, and the building extensively renovated. A dress circle was added, increasing the seating capacity to 1000 seats.[50]

After a fire gutted the building in early 1934, it underwent reconstruction and extension in September of that year, to designs by F. Kenneth Milne. It is thought to be one of the first buildings in South Australia created in the style known as streamlined, a type of Art Deco that became popular in the 1930s.[49] On 21 December 1934 the Victor Theatre reopened as an Ozone cinema.[50] The cinema had a seating capacity of 910 at the time of its takeover by Hoyts in 1951. It operated restricted opening times from 1960 onwards, and from 1963 closed during the winter.[51]

In 1970 it was acquired by independent operator Roy Denison for A$25,000, who reopened it as the Victa Theatre.[50] Manager Geoff Stock bought the cinema upon Denison's retirement in 1995,[50] and it was fully renovated and renamed Victa Cinema. Twin screens were created in August 1998, with the former balcony screen seating 286, and the screen in the former stalls screen seating 297.[51] In 2005 it was bought by David and Carol Stonnill, who upgraded the building further, while retaining the Art Deco character. In October 2020 the City of Victor Harbor purchased the cinema, intending to include it in the town's Arts and Culture centre in the future.[50]

The Victa has been state heritage-listed and retains its Art Deco fittings. It was featured in a photographic exhibition called Now Showing... Cinema Architecture in South Australia held at the Hawke Centre's Kerry Packer Civic Gallery in April/May 2024.[52]

Wonderview Theatre[edit]

The Wonderview Theatre was located on Flinders Parade,[49] opposite the Soldiers' Memorial Gardens.[17] The company selected the name "Wonderview" from 87 public submissions in October 1923.[53] The "Wonderview De Luxe Beach Theatre", like the Victor, was also designed by Chris A. Smith. It was described as being "palatial"; wider than the older long narrow theatres, with a latticework ceiling containing concealed lighting, comfortable seating that included settees. Its equipment was modern and it included a dance floor made of Queensland hoop pine, a soda fountain, and tea room. It was officially opened on 22 December 1923 by the mayor W. F. Connell with great fanfare, and lauded for its ability to attract more visitors to the town. It was announced that the dance floor would be opened for dancing on Monday and Friday nights.[17] It was licensed to accommodate 696 patrons.[49][17] A week before the official opening, a children's fancy dress parade was held in the building, on 15 December 1923.[54]

The Wonderview was co-owned by a number of local shareholders,[17] and operated by National Pictures Limited, which also operated suburban Adelaide cinemas The National at Prospect, National Pictures in North Adelaide, and the Parkside Picture Pavilion at Parkside.[55] Local man E. G. Fairbairn was appointed manager of the Wonderview in November 1923.[56]

In January 1928, after National Theatres went into liquidation, Ozone Theatres acquired freehold ownership of the building.[49] Although the Wonderview was larger, Ozone concentrated its efforts on the Victor, installing a Western Electric sound system there, and the Wonderview went into a decline.[49] It started closing in the winter months from 1928,[55] and from February 1930 was the home of a government high school during the day, doubling as a dance hall at night.[49]

In January 1931, after the Victor Theatre was damaged by fire and it was closed for the rest of that year, the Wonderview started showing films again, possibly using the sound equipment that had been installed in the Victor the previous year.[55] By December 1931, the Wonderview was used mainly as a dance hall,[55][57] as well as special fundraising events[58] and showings of films on Wednesdays and Saturdays, including Tarzan and His Mate, starring Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O'Sullivan, in October 1934.[59] On 19 September 1934, "Victor Harbour Day", there was a special screening of films at the Wonderview.[49] By the Christmas-New Year season of 1934, the building was known as the Wonderview Palais, with dancing on most nights, including New Year's Eve.[60][61]

From January 1939, the building was put to a variety of uses, including a tanning salon,[62] J. Miller Anderson & Co. sale,[63] church services,[64] and residences.[65] On 26 December 1941, Ozone Theatres held a gala reopening of the venue,[66] and experienced a new lease of life as a picture theatre during World War II owing to the number of service personnel swelling the population of the town.[55]

The Wonderview was demolished in 1991.[49]

Other historic buildings[edit]

There are many local and state heritage-listed buildings in Victor Harbor, some of which are mentioned above.[67]

Adare House[edit]

Adare House (as of 2024[update] known Adare Conference Centre) was listed on the South Australian Heritage Register in 1999.[68]

The land on which Adare House was built was known to the Ramindjeri people as mootiparinga, meaning murky or brackish water. In the first year of colonial settlement, the colony of South Australia's first governor, John Hindmarsh, purchased the land. His son John built a small house on the property in the 1860s.[69]

Daniel Henry Cudmore, a pastoralist and businessman, bought the property in 1889. Based on designs by architect Frederick William Dancker[69] (1852–1936),[70] the original house was rebuilt and expanded it to include 19 rooms, a cellar, a tower, a balcony, and three turrets. It was completed in 1893. It is located on the outskirts of the town, next to the Hindmarsh River. Since the second half of the 20th century, Adare House has been used by the Uniting Church for group camps, and the grounds used as a caravan park. Since the 21st century, the building has been used for weddings and other private functions.[69]

Dancker also designed a residence, Attunga, that is now part of Burnside Hospital; the Queen Victoria Hospital, St Paul's Lutheran Church at Hahndorf, and the Malvern Uniting Church.[68][71]

Others[edit]

Other buildings listed on the South Australian Heritage Register include:[72]

- St Augustine's Anglican Church

- Former Victor Harbor Post & Telegraph Office and Postmaster's Residence, now an art gallery

- Victor Harbor Town Hall & Library (formerly Institute)

- National Trust Museum (former Victor Harbor Custom House & Station Master's Residence)

- Anchorage Guest House (former Aurora House, later Warringa Guest House), 20-23 Flinders Parade

- Grosvenor Hotel, 32-44 Ocean Street

- BankSA (former Savings Bank of South Australia Victor Harbor Branch)

- Second Newland Memorial Uniting (former Congregational) Church, 20-28 Victoria Street

- Victor Harbor Uniting Church Hall (former First Newland Memorial Congregational Church)

Climate[edit]

Victor Harbor has a warm summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb).[73] Summer average temperatures are significantly lower than most of the state, due largely to the sea breeze moderating temperatures and hot northerlies rarely extending past the hills north of the city.[citation needed]

| Climate data for Victor Harbor (5m ASL) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 44.0 (111.2) |

43.0 (109.4) |

41.6 (106.9) |

35.5 (95.9) |

28.9 (84.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

33.7 (92.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

41.1 (106.0) |

42.0 (107.6) |

44.0 (111.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 20.8 (0.82) |

19.6 (0.77) |

22.9 (0.90) |

43.0 (1.69) |

61.6 (2.43) |

71.2 (2.80) |

74.8 (2.94) |

67.4 (2.65) |

56.2 (2.21) |

45.5 (1.79) |

28.0 (1.10) |

24.1 (0.95) |

535.1 (21.05) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 4.5 | 4.4 | 6.4 | 10.1 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 16.5 | 16.3 | 13.6 | 11.4 | 7.8 | 6.5 | 126.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 60 | 62 | 62 | 66 | 69 | 67 | 63 | 63 | 59 | 57 | 61 | 62 |

| Source: Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology[73] | |||||||||||||

References[edit]

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Victor Harbor (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Victor Harbor, South Australia". Postcodes Australia. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ "Fleurieu Kangaroo Island SA Government region" (PDF). The Government of South Australia. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "District of Finniss Background Profile". ELECTORAL COMMISSION SA. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ "Federal electoral division of Mayo, boundary gazetted 16 December 2011" (PDF). Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ HMS Victor, 1814, Index of 19th Century Naval Vessels, www.pbenyon.plus.com/18-1900

- ^ South Australian State Gazeteer

- ^ Established as "Victor Harbor". "Municipality of Victor Harbor Constituted" (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2019. The South Australian Government Gazette, 1914, page 1165, 28 May 1914.

- ^ "Municipality of Victor Harbor Constituted" (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2019. The South Australian Government Gazette, 1914, page 1165, 28 May 1914.

- ^ "Harbor proclaimed under the Harbors Act, 1913" (PDF). Retrieved 20 June 2019. The South Australian Government Gazette, 1915, page 331, 15 July 1915.

- ^ "Harbor proclaimed under the Harbors Act, 1913" (PDF). Retrieved 20 June 2019. The South Australian Government Gazette, 1921, page 1267, 16 June 1921.

- ^ "Naming of Our Town". Retrieved 20 June 2019. Victor Harbor Times, 27 September 1963, page 4.

- ^ a b "Victor Harbor or Victor Harbour?". Retrieved 20 June 2019. State Library of South Australia SA Memory.

- ^ Editions 8 September 1922 to 22 March 1978. "Refer digital copies of paper at Trove". Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Why is Victor Harbor spelt without the 'u'?". Archived from the original on 12 March 2011.

- ^ "National Pictures". News (Adelaide). Vol. X, no. 1, 419. South Australia. 31 January 1928. p. 2 (Home edition). Retrieved 29 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d e "Official opening". The Victor Harbor Times and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot. Vol. XII, no. 590. South Australia. 28 December 1923. p. 3. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Walker, Terry (1995). Fast Tracks – Australia's Motor Racing Circuits: 1904–1995. Wahroonga, NSW: Turton & Armstrong. p. 170. ISBN 0908031556.

- ^ Galpin, Darren. "Victor Harbor". GEL Motorsport Information Page. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ Peddie, Clare (30 October 2021). "Sea surge sending either bowls or beaches to the wall". The Advertiser.

- ^ "Mayor vows to be 'first one to lie in front of a bulldozer' to prevent marina project". ABC News. 6 November 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Mayor vows to be 'first one to lie in front of a bulldozer' to prevent marina project". ABC News. 6 November 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Harbor, City of Victor (3 February 2017). "Council Information". City of Victor Harbor – via victor.sa.gov.au.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Victor Harbor (State Suburb)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Victor Harbor Urban Growth Management Strategy 2008–2030 prepared by Nolan Rumsby Planners

- ^ "Victor Harbor - Goolwa, Census All persons QuickStats". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Island security under review". Times. 25 June 1998. p. 1. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Washington, David (16 December 2022). "Granite Island little penguins' big decline". InDaily. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Horn, Caroline (28 October 2023). "Flinders University researchers encouraged as little penguin numbers increase on Granite Island". ABC News. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "The Cockle Train". SteamRanger Heritage Railway. 24 February 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Manners, Amy (17 December 2019). "SA Whale Centre's humble origins". The Fleurieu App. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b Burton, Alice (18 December 2022). "NOW OPEN: Victor Harbor unveils new combined whale and visitor centre". Glam Adelaide. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "South Australian Whale Centre". Victor Harbor. 15 January 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "Top Surf Spots On The Fleurieu Peninsula & Tips To Surf Them". Victor Harbor. 14 September 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Surf info". Surfsouthoz. 28 December 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Urimbirra Open-Range Wildlife Park". Urimbirra Wildlife Park. 2 May 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Soldiers' Memorial Gardens, Victor Harbor". The South Australia Heritage Places database. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Simmons, Michael (10 September 2015). "Greenhills Adventure Park to close on May 1, 2016". Victor Harbor Times. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Schoolies Festival™ Victor Harbor". Encounter Youth. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Harbor, City of Victor (8 March 2014). "Dry Areas". City of Victor Harbor – via victor.sa.gov.au.

- ^ "The Victor Harbor Art Show 2020". victorharborartshow.com.au.

- ^ "Victor Harbor Art Show". 17 October 2016.

- ^ "The Victor Harbor Times and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot (SA : 1912–1930)". Trove. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "Times Victor Harbour and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot (SA : 1930–1932)". Trove. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "Victor Harbour Times (SA : 1932–1986)". Trove. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ South Coast news [newspaper: microform]. Victor Harbour, S. Aust: A.H. Ambrose. 1965.

- ^ South Coast sports news [newspaper: microform]. Victor Harbor, S. Aust: The Ambrose Press. 1969.

- ^ "National Pictures". News (Adelaide). Vol. X, no. 1, 419. South Australia. 31 January 1928. p. 2 (Home edition). Retrieved 29 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i South Australian Heritage Council (25 November 2022). "Summary of state heritage place: Victa Cinema (former Ozone Theatre)" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e "History". Victa Cinema. 24 November 1923. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ a b Roe, Ken. "Victa Cinema in Victor Harbor, AU". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Meegan, Genevieve (19 April 2024). "'Now showing' – celebrating Adelaide's cinema heyday". InReview. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Advertising". The Victor Harbor Times and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot. Vol. XII, no. 581. South Australia. 26 October 1923. p. 2. Retrieved 29 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "At Victor Harbour". The Observer (Adelaide). Vol. LXXX, no. 5, 996. South Australia. 29 December 1923. p. 52. Retrieved 29 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d e "Wonderview Theatre, Victor Harbour". Encyclopaedia of Australian Theatre Organs. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Movie Movements". The Victor Harbor Times and Encounter Bay and Lower Murray Pilot. Vol. XII, no. 586. South Australia. 30 November 1923. p. 3. Retrieved 29 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Holidaymakers on the dance floor at the Ozone Theatres' Wonderview Dancing Hall, at Victor Harbor" (photo + caption). News (Adelaide). Vol. XXI, no. 3, 259. South Australia. 29 December 1933. p. 8. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Victor Harbour Day". Victor Harbour Times. Vol. XXII, no. 1143. South Australia. 14 September 1934. p. 2. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Advertising". The Advertiser (Adelaide). South Australia. 6 October 1934. p. 13. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Advertising". The Advertiser (Adelaide). South Australia. 22 December 1934. p. 3. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Dancing At Victor Harbour". The Advertiser (Adelaide). Vol. LXXIX, no. 24409. South Australia. 1 January 1937. p. 13. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Modern health salon". Victor Harbour Times. Vol. XXVII, no. 1371. South Australia. 13 January 1939. p. 2. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Advertising". The Advertiser (Adelaide). South Australia. 8 March 1939. p. 7. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Advertising". The Advertiser (Adelaide). South Australia. 8 April 1939. p. 6. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "News in brief". Victor Harbour Times. Vol. XXVII, no. 1412. South Australia. 27 October 1939. p. 3. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Advertising". Victor Harbour Times. Vol. XXVII, no. 1522. South Australia. 26 December 1941. p. 3. Retrieved 30 April 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Search By Location - Suburb: VICTOR HARBOR; LGA: ALL; Class: ALL". The South Australia Heritage Places database. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b "7-27 Adare Avenue VICTOR HARBOR". The South Australia Heritage Places database. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b c "Adare House Conservation Appeal – National Trust". National Trust. 11 May 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Architect Details: Dancker, Frederick William". Architect Details. University of South Australia. 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "Architect Details: Dancker, Frederick William". Architect Details. University of South Australia. 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "Search By Location - Suburb: VICTOR HARBOR; LGA: ALL; Class: S". The South Australia Heritage Places database. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Climate Data Online for Victor Harbor (Weather station closed 01 Apr 2002)". Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Hodge, Charles R. (Charles Reynolds) (1930), Guide-book to Victor Harbour, the miniature Naples of Australia and the south coast, C.R. Hodge, retrieved 18 March 2018