Limehouse Basin

Limehouse Basin is a body of water 2 miles east of London Bridge that is also a navigable link between the River Thames and two of London's canals. First dug in 1820 as the eastern terminus of the new Regent's Canal, its wet area was less than 5 acres (2 hectares) originally, but it was gradually enlarged in the Victorian era, reaching a maximum of double that size, when it was given its characteristic oblique entrance lock, big enough to admit 2,000-ton ships.

Throughout its working life the basin was better known as the Regent's Canal Dock, and was used to transship goods between the old Port of London and the English canal system. Cargoes handled were chiefly coal and timber, but also ice, and even circus animals, Russian oil and First World War submarines. Sailing ships delivered cargoes there until the Second World War, and can be seen in surviving films and paintings. The dock closed for transshipment in 1969 and eventually passed into disuse. Following closure of the basin and much of the wider London docks, the surroundings were redeveloped for housing and leisure in the late 20th century. Sometimes now referred to as the Limehouse Marina, the Basin lies between the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) line and historic Narrow Street; the Limehouse Link tunnel passes beneath. Directly to the east is Ropemaker's Fields, a small park.

History

[edit]Reasons for construction

[edit]

Fuel for London; Thames congestion

[edit]To warm their homes and cook their food Londoners at one time burned wood, but local woodlands, though managed as renewable resources, could not keep up with the rising demand.[1] Thus by the 18th century the town's fuel was chiefly coal, imported from Newcastle upon Tyne by sea[2] — hence, sea coal. It was transported in colliers, typically small brigs. Because voyages could be extremely hazardous,[3] these were built for strength, "certainly not for looks".[4]

Arriving in the Thames, a collier tried to find a mooring in the highly congested[5] Pool of London.[2] Once moored, a fleet of small barges, called lighters, relieved her of her cargo.[6] But these lighters were used as floating warehouses, perhaps taking a long time to unload. They attracted "River-Pirates, Night-Plunderers, Lightermen, Burgemen, Watermen, Bumboatmen, and Peter-Boatmen", to the point that rivermen rarely paid for their coals, or so said Patrick Colquhoun, founder of the Thames River Police.[7]

Linking Port to English canal system

[edit]Some inland towns depended on the English canal system for their coals, yet access from the Pool of London was difficult, the nearest Thames link being at Brentford.[8] The Regent's Canal Company proposed to tackle this problem by digging their canal to skirt round existing London to the north. Horse-towed barges would convey goods from Limehouse to the Paddington Branch of the Grand Union Canal (opened 1801),[9] and onwards. "The Regent's Canal was intended to and still does bring the Thames into watery contact with, say, Birmingham".[10] Later, it was sometimes found cheaper to import coal in the opposite direction. The Newcastle mine owners were in a cartel to keep up prices and, when they went too far, midland coalfields sent their produce to London down the Regent's Canal.[11]

Where a canal joined a tidal river there was usually a small basin where barges could wait for the right state of the tide to go over.[12] The Regent's Canal Company, short of capital, thought it would be enough to provide a small 1 1⁄2 acre basin of that sort at Limehouse. However, they were converted to a bolder idea: making it big enough to receive the Newcastle sailing colliers themselves, which could then unload at their convenience.[13]

The Basin: original 1820 version

[edit]

The chief engineer was James Morgan and the contractor was Hugh McIntosh; the basin's wet area was 4 1⁄2 acres.[14][15]

The basin formally opened on 1 August 1820.[16] The Regent's Canal entered the basin through the Commercial Road Lock, which is still in use.

The original basin was rudimentary. It was not faced with stone or brick but, to save disposal of spoil, had earthen banks gradually sloping down to the bottom,[17][18] which was 18 feet (5.5 m) below Trinity High Water.[8] Since ships could not get alongside to moor there were wooden jetties for discharging goods to local merchants, but they had been built too high. There were not enough mooring buoys.

The Basin was gradually enlarged in the 19th century by digging east and southeast (see below). At the century's end parts of the west and north banks were sloping still.[19]

Thames entrance

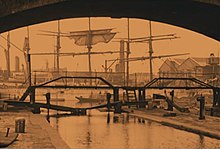

[edit]The Basin was dug some distance inland, since the riverfront was built up. It was connected to the Thames by a short canal that was crossed by two streets. It had a pound lock, and could admit ships of about 10 metres beam.[20] (This canal outlet ran more or less where Horseferry Road does today as it joins Narrow Street.) Traffic on Narrow Street crossed the canal by a swing bridge, which could pivot out to let vessels pass, driven by labourers who worked capstans (see artist's impression).

The canal outlet was made nearly square-on to the river, but it turned out to be a bad choice. When ships were trying to dock or undock, the local set of the tide flowed crossways, making it very difficult.[21] In the first five months' service only 15 loaded ships entered the dock.[18]

Not only ships, but already-laden barges entered the Basin from the Thames.[22]

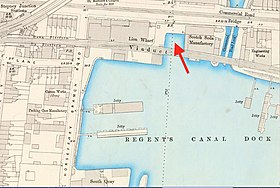

Not the first Limehouse basin

[edit]Limehouse Basin was the third structure of that name in London.[23] In any case half of it lay in the parish of Ratcliff, not Limehouse.[24] Hence throughout its working life it was better known as the Regent's Canal Dock;[25] its "RCD" flag can be seen in the 1826 artist's impression.

-

Limehouse Basin 1827 with shipping and barges; notice the sloping banks

-

Horwood's map 1819 (black arrow = Limehouse Basin, white = Limehouse Cut)

-

Artist's impression of Thames entrance, 1826 with its capstan-operated swing-bridge

-

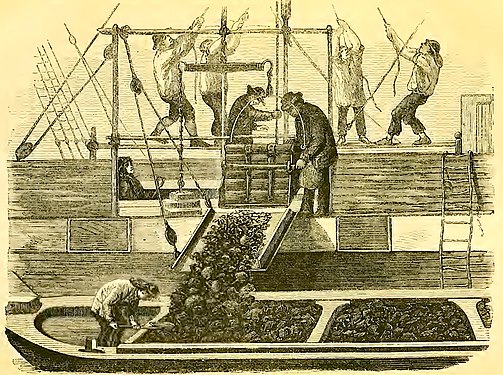

Coal-whippers. Four men could lift 100 tons of coal a day.

Muscle power: coal-whipping

[edit]Coal was unloaded in the Basin from ships to barges. Until 1853 it was done entirely by human muscle power in a method called whipping.[26] Four men down in the ship's hold put lumps of coal into a basket as fast as they could. Up on deck, another four men, when they guessed the basket should be full, ran up a crude ladder and jumped down onto the deck simultaneously, each throwing his weight onto a rope passing over a pulley: this jerked (or whipped) the basket out of the hold. Keeping up the momentum, a ninth man tipped the contents into a weighing machine which shot them into a barge. The whole thing was done in silence. A nine-man gang was expected to unload 49 tons of a coal a day; more often, according to Henry Mayhew, they achieved double that amount — during which each rope man climbed a total distance of nearly 1 1⁄2 vertical miles — and sometimes more.[27]

Modifications and success

[edit]The proprietors soon fixed the teething troubles about the jetties and mooring buoys and the project became a success. By 1830, twenty to fifty vessels were entering or leaving the basin on each tide, typical large users being the London gasworks companies.[28]

To cope with the currents a timber structure was erected to protect vessels being driven sideways (illustration). Nevertheless, wrote engineer John Baldry Redman in 1848, the entrance bore "a very bad character".[21]

-

The Basin's Thames entrance in 1850 with its protective timber structure

-

The London & Blackwall viaduct (1840), now carrying the DLR, crossing the Commercial Road Lock

The London and Blackwall Railway arrived in 1840. Built on a viaduct, its arches skirted the northern edge of the dock, sometimes actually crossing the water. Thus the dock included a small basin on the other side of the railway line where barges could enter;[12][29] it was not filled in until 1926.[30]

The railway continued to carry passengers until 1922 and goods until 1964, when it was abandoned,[31] and was in danger of demolition,[32] but its "fine" arches (by Robert Stephenson and George Bidder) were preserved as a listed building;[33] today, they are used by the Docklands Light Railway.

The dock was enlarged several times (by 1848 the water area was 8 1⁄2 or 9 acres)[8] and, in 1849, to cope with increasing congestion, a second outlet to the river was made for barge traffic.[34]

In 1851 severe competition arrived: the railway companies penetrated the coal trade. Not only was coal from Yorkshire and the Midlands carried direct to King's Cross by the Great Northern Railway, but the North London Railway opened a line to the West India Docks, whose Poplar Dock could handle the latest large, efficient twin-screw steam colliers.[12]

In Limehouse Basin, human muscle could not unload coal fast enough; electrical power was not yet practical; so in 1853 hydraulic power was fitted. Energy was stored in hydraulic accumulators (a heavy weight on a water column driven up a tower by a steam engine), a cutting edge technology at the time.[12] It drove hydraulic cranes.[12]

Mid-Victorian improvements (1870)

[edit]By 1865, the Basin was overcrowded.[8] The old ship canal was not wide enough for the big steam colliers that were winning the business.[35][12] It was the only dock entrance in London too narrow to admit the Fire Brigade's floating engine (a paddle-wheeler).[36] A major scheme of improvements was carried out. The work was done by the Company's own employees under their chief engineer, Edwin Thomas.[8]

The wet area was increased to 10 acres, the most[37] it ever[38] attained.[39] A new river wall was erected. Meanwhile, it was business as usual, for the shipping traffic continued to come and go, floating in the old basin while protected by an earthen dam (see illustration).[8]

-

Enlargement (top-hatted directors posing, early 1867). Note sailing ships — held back by temporary earth dam.

-

Limehouse Basin in its heyday. The new slantwise shiplock is in the centre; old ship and barge locks on left.

-

The north quay jetty drawn by Gustave Doré.[40] Notice hydraulic cranes.

-

1880 Plan issued by Regent's Canal Company to advertise their dock. The old ship lock has been closed off.

Ship lock

[edit]The most important innovation was the new ship lock, which was 18.5 metres (61 ft) wide, and built slantwise to avoid the previous troubles. It was 8 +1⁄2 metres deep over the sills. Major parts were made of Bramley Fall stone or Cornish granite.[8] It could admit sea-going vessels of 2,000 tons net register,[41] far more than would be possible now[25] (today's lock is built inside the 1869 original). It was a two-compartment lock, and hence there were three lock gates, each formed by a pair of leaves. Each 80-ton gate leaf rested on a massive granite pivot stone.[42] Most of those stones — with their telltale circular depressions — have been preserved, and today are laid out on display on the western side of the Basin.

Limehouse Basin now had three entrances from the Thames. The old ship lock was closed off by 1880, but the barge lock continued to exist until about 1924.[30]

The accumulator tower

[edit]

To work the heavy lock gates, hydraulic power was used; it also worked the swing bridge over Narrow Street, and continued to power the hydraulic cranes. For this purpose a new[43] hydraulic accumulator was built with an unusual octagonal brick tower.

In 1973, investigators found the remains of the tower and at first mistook it for a railway signalling installation. It is now recognised as one of the oldest surviving accumulator towers in the world and is a Grade II listed building, being open every year during Open House Weekend.[26]

Jobs

[edit]Alan H. Faulkner[44] wrote that in 1907 Limehouse Basin employed (amongst others) a dock master, six policemen, thirteen crane drivers, and a diver and his mate.

Exotic cargoes and transport

[edit]The Company made efforts to diversify the dock's trade beyond coal and timber and attracted miscellaneous shipping.

Edible ice

[edit]

Before mechanical refrigeration was commonplace, Limehouse Basin was a centre for the importation of high grade ice, in demand by caterers, confectioners and hospitals. Ice, pure enough for human consumption,[45] was cut in blocks from frozen Norwegian[46] lakes, shipped to Limehouse Basin, and stored in ice wells located near the Regent's Canal. The first to do this was William Leftwich.[47] His enormous[48] Park Crescent West ice well near Regent's Park has been rediscovered recently under the streets of Marylebone.[49][50] He built ice wells in Cumberland Market and Camden Market, also supplied by the Regent's Canal from Limehouse Basin,[51] One, the deepest ever dug, survives to this day.[52]

Ice cream was a luxury for the well-to-do until Carlo Gatti introduced it to Londoners as street food — his penny ices.[53] He built two ice wells at Kings Cross;[54] one of them can be visited at the London Canal Museum.[55] Gatti's depot was on the north-east side of Limehouse Basin for many years. At least 15 ice ships a year were still arriving there in 1912.[44]

Ice had six different medical uses at the East End's London Hospital wrote their Matron, Eva Luckes.[56] At one time it was commended as a safer anaesthetic than chloroform for "minor" amputations e.g. finger removals.[57]

Cruises to Liverpool

[edit]In the Victorian era there was a weekly passenger service from Limehouse Basin to Liverpool; the round trip could be booked as a holiday cruise. Leaving on Saturday mornings, ships steamed round the west coast calling at Plymouth and Falmouth arriving in the Mersey on Wednesdays. The fare was £1 plus meals. One who had tried it said it was not recommendable during the equinoctial gales.[58] Another said there were cabins but a passenger might have to sleep in the lifeboat.[59]

Oil tankers

[edit]

Some of the earliest practical oil tankers — before those evolved, ships routinely transported oil in barrels[60] — docked in the Limehouse Basin in 1886. One was the innovative oil-fired Russian steamer Sviet with petroleum from the Baku oilfields;[61] another was the American Crusader a wooden sailing tanker. The ships were designed to pump out their cargo quickly, saving valuable docking time, but could not do so at Limehouse Basin, because there were no bulk storage facilities. It had to be piped overland to barges in Limehouse Cut.[62]

Circus animals

[edit]The Limehouse Basin between the wars was used to import animals — including lions, tigers, elephants, polar bears and sea lions — on their way to the London and provincial circuses. Once, 14 tigers arrived in one batch.[63][64]

Submarines

[edit]After the First World War 25 German submarines were towed into Limehouse Basin and broken up by scrap merchants George Cohen & Sons, whose business was located between Commercial Road lock and the station.[65]

Oranges

[edit]Near present-day Medland House in the 1920s were electric cranes for handling fruit cargoes from Spain.[12]

20th-century sailing ships

[edit]The use of sailing ships to deliver timber at Limehouse Basin continued up to WW2.[66] Labour-intensive, it was financially viable because most crewmen were youths who were paid no wages.[67] The ships can be seen in films of the silent era; a painting at the National Maritime Museum by Norman Janes shows three 3-masted sailing vessels there at the same time.[68]

The Regent's Canal dock had its own customs house. The latest was built around 1905-10, and stood on the river side of the Thames lock. Today, it is a listed building,[69] and is used as a Gordon Ramsay gastropub.

Relation with Limehouse Cut

[edit]

Limehouse Cut to the east — an older canal that conveyed grain traffic from the River Lea and had its own basin and exit to the Thames — had no historic connection with the Regent's Canal. In 1854, however, there was talk of a takeover and a link was dug to Limehouse Basin. The takeover was opposed by bargemen on the rivers Lea and Stort who did not like being under Regent's Canal regulations. The proposal was defeated and in 1864 the link was filled in.

Apart from that brief interlude there was no connection between Limehouse Basin and the Cut for another hundred years, although some old maps may suggest otherwise.[70]

In 1968 Limehouse Cut's old Thames exit was stopped up and, by cutting a 200 foot (60 metre) channel, it was made to discharge directly into Limehouse Basin.[25] (The new link ran north of what is now Victory Place. The old link had run to the south of the site.)

Lifeboats

[edit]The Victorian era's lifeboats, sponsored by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, were built nearby on the Limehouse Cut at Forrestt's boatyard, but for publicity were often given their harbour trials in Limehouse Basin. They were tipped upside down and allowed to fill with water: if they self-righted, spontaneously ejecting the water, they passed.[71][72][73] Reportedly these boats saved upwards of 12,000 lives.[74]

In national politics

[edit]On 1 January 1948 the Regent's Canal was nationalised.[75] On 27 May 1948 eleven dockers were ordered to load bags of a chemical onto a ship docked in Limehouse Basin. Because the chemical stained their skin and clothing they felt it was a dangerous cargo and refused to handle it, unless for extra payment of their own specifying. This was a direct challenge to the National Dock Labour Scheme instituted by the newly elected Labour government, which had replaced the old system of casual employment by a legal right to minimum work, holidays, sick pay and pensions, but under a regime where dockers had to obey orders or face disciplinary action (although they could appeal). The dispute escalated to a London-wide dock strike, spreading to Liverpool, whereupon the Attlee government invoked emergency powers and ordered troops to unload food vessels.[76]

Swing bridge

[edit]The swing bridge that carries Narrow Street over the Thames lock is a 1961 replacement.[77] Built on Teesside, to get it to London it was made into a seaworthy pontoon and towed down the North Sea.[25]

Redevelopment

[edit]

Derelict

[edit]Burning coal in London was made illegal. The last commercial barge traffic in Limehouse Basin was in April 1968. It closed as a transshipment dock in 1969, though it continued to be visited by ships with scrap metal for Cohens as late as 1980.[25] It became a bleak, derelict industrial zone.[78] Planners wanted to fill it in "because they said children would fall in and drown".[79] Also, the area was blighted by traffic congestion, access to the Isle of Dogs being poor. The Greater London Council proposed to demolish part of the railway viaduct and replace it by a 4-lane dual carriageway;[32] an alternative route was between the Thames and the Basin, which would have cut through the exit lock.[80][25]

Controversy

[edit]The redevelopment of the Basin for housing started in 1981 when the British Waterways Board organised an architectural competition.[81] The winner was a £70 million scheme by the controversial[82] architects Richard Seifert and Partners. It called for half of the Basin to be filled in to provide 100,000 square feet of offices and 400 luxury houses. It was strongly opposed by local residents, including David Owen, and was refused by the planning inspector who, however, was overruled by the Secretary of State.[83][84] The architectural controversy attracted Prince Charles, who made a surprise visit to the Basin.[85] The scheme was never fulfilled,[86] except for Goodhart Place. Instead, the Basin was developed in phases, as and when the financial climate permitted.[87]

Under the Basin: Limehouse Link

[edit]The answer to traffic congestion, said the London Docklands Development Corporation, was to run the Limehouse Link tunnel under the northern arc of the Basin. No precedent existed for such a large scale underground structure in those conditions. Since it was close to the DLR, precautions were needed to stop ground movements from collapsing the 150-year old brick viaduct.[88]

The top ground was first consolidated by removing silt with a floating dredger and replacing it with North Sea aggregate to reclaim a stretch of dry land. The tunnel was made by the cut and cover, bottom up[89] method. The trench was excavated inside a temporary cofferdam formed by massive[90] piles braced by steel struts. The piles were very difficult to drive in the over-consolidated London Clay — and afterwards to remove.[91] The first test pile was driven by Margaret Thatcher on 20 November 1989.[92] Further precautions were taken to weight the base slab — if the groundwater pressure is high enough, even a concrete tunnel will float — and also not to form a new hydraulic connection between the Basin and the aquifer in the lowest stratum of the Woolwich and Reading Beds. The Regent's Canal was closed off for a year.[91]

The four Marina Heights buildings were afterwards built over the tunnel. Wet basin area was restored in some other places e.g. the canal mouths by removing the marine aggregate.

New lock

[edit]The old mid-Victorian shiplock was large and used a lot of water, so in 1988-9 the Thames lock was rebuilt to much smaller dimensions. The new lock is only 24 feet (7.3 metres) wide — even less than the 1820 original — and the depth over the sills is 10 feet.[25] It was rebuilt within the confines of the 1869 ship lock, whose outline can still be seen.

Amenities

[edit]Facilities alongside the Basin include a Gordon Ramsay gastropub, a tai chi academy, a gym, a kayak hire, a fine arts bronze foundry and gallery, and a cosmetic dental practice. Immediately near is the historic pub The Grapes, an Italian restaurant, a hair studio and a dry cleaner. In Ropemaker's Fields (a small park immediately to the east) there is a children's playground and a tennis court.[93] Limehouse DLR station is beside the northwestern corner of the Basin. St Anne's Limehouse (1730), a Grade-1 listed building by Nicholas Hawksmoor,[94] is a familiar landmark.

The canals offer recreation for narrowboats and kayaks; their towpaths, for walkers and cyclists. A six-mile round trip is: up the Limehouse Cut to join the Lee Navigation, then west by Duckett's Canal to join the Regent's Canal, then south back to Limehouse Basin.

Housing immediately alongside the Basin includes Goodhart Place, the apartment blocks Medland House, Berglen Court, Pinnacle 1 (awarded Best Apartment Building 2001),[95] Marina Heights (four), Pinnacle 2, two terraced town houses and Victory Place. The Basin (excluding its buildings) is part of the Narrow Street Conservation Area.[96] Canary Wharf is within walking distance; the scenic river route is across Narrow Street and using the bridge over Limekiln Dock. It can also be accessed by the 135 and D3 buses, or by the DLR.

Marina

[edit]

The Cruising Association has a purpose-built headquarters at Limehouse Basin,[97] where a number of vessels, both sea-going and narrowboat type, are permanently moored. There are facilities appropriate to a marina, such as secure jetties, diesel supply, laundry, shower, chemical toilet disposal, a pump-out and a chandlery.[98]

"According to several boating associations",[99]

the Limehouse Basin is a vital ‘port of refuge’ for departing and visiting craft from further down the tidal Thames and the Continent, due to providing the only lock in central London with an adequate tidal window for barges travelling downstream from the non-tidal Thames and other moorings and basins.

Of the berths, 75 are for permanent waterside living; others are for leisure use, wintering vessels, or visitors. The Thames lock operates 2 hours either side of low water.[98]

At the Marina Office a plaque commemorates Stephen Maynard, a fireman who lost his life on 25 January 1980 putting out a ship fire in the dock: he was 26. In 2016 colleagues were still holding an annual minute's silence in his memory.[100]

How deep is Limehouse Basin?

[edit]The depth of the Basin is variable. When it used to be a working dock it was supposed to be at least 6 metres deep and regularly dredged to keep to that standard;[75] but this is no longer so. The Limehouse Link tunnel was made deep enough to give a minimum draft of 3 metres for canal barges.[101] At the Thames entrance lock the depth over the sills is also 3 metres.[25]

Wildlife

[edit]

According to the Canal & River Trust

Limehouse Basin sits at the junction of three important 'green corridors'. The River Thames, Regent's Canal and Limehouse Cut all meet here, each providing a green highway along which wildlife can move around the built up area.[102]

Birds that live there or are regular visitors include coots, moorhen, geese, black headed gulls, ducks (including red-crested pochards), cormorants, common tern, grey heron, and the occasional kingfisher. There is usually a pair of nesting mute swans.

Fish include bream, roach, pike and occasional eels.[103]

In some hot seasons a "green carpet" descends from the canals and can cover much of the Basin. This is not "algae", but duckweed. While it can be a nuisance on canals, it is harmless to humans[104] and is an important high-protein food source for waterfowl.

In literature and broadcasting

[edit]

Maidens' Trip (1948) by Emma Smith describes the wartime experiences of three "dainty young girls" who, as part of their national service, volunteered to load and navigate barges from Limehouse Basin to Birmingham and back — with only a bucket for a lavatory. Recalled Smith:

1944 was the year the doodle-bugs were being sent over from the Continent, and the job of taking the boats down to the docks for loading and away again was like an adrenalin-fuelled dash in and out of Tom Tiddler's ground. Nobody wanted to get caught for the night in Limehouse Basin. It was said, and probably with truth, that if a bomb were to drop in the basin every boat lying there would be sucked under and sunk.

(Although no V1 flying bombs did drop into Limehouse Basin, three exploded within yards of it.)[105]

The real canal boatmen travelled with their families, their wives giving birth on board; the babies (wrote Smith) were "little creatures who would pass their early days chained for safety to the chimney-pots".[106]

The book was adapted for radio (1968) and television (1977).

Archaeology

[edit]Archaeologists had an opportunity to look underground when Limehouse Basin was redeveloped. Beside the Thames lock, at Victoria Wharf, a team found the remains of an earlier dock, whose timbers they dated to 1584-5 by dendrochronology. There was evidence of shipbuilding around the time of the Spanish Armada. Coins and other finds came from as far afield as Cuba, Persia, and China.[107]

While excavating the Basin for the Limehouse Link a 16th-century cannon was found.[108]

Another team excavated a site on the other side of the lock. Finds showed the 16th and 17th century occupants were exceptionally wealthy men and women. "Meals were likely to be served on fine Mediterranean tableware and wine taken in glasses derived from the finest production centres of the age". The archaeologists realised it had been inhabited by retired pirates of the Caribbean, some of whom they were able to identify by name.[109]

References and notes

[edit]- ^ Galloway, Keene & Murphy 1996, p. 449.

- ^ a b Hausman 1977, p. 461.

- ^ Hausman 1977, p. 472. There was an incident early in the 18th century in which over 200 ships were lost at one time.

- ^ Hausman 1977, pp. 461-462n..

- ^ Ville 1986, p. 364. In 1829 it was decided that no more than 250 colliers should be allowed in the Pool at the same time.

- ^ Ville 1986, p. 363.

- ^ Colquhoun 1800, pp. 27–28, 141–8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colburn 1869, p. 384.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, p. 70.

- ^ Hunter 2019, p. 318.

- ^ Tan 2009, p. 353.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith 1993.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, pp. 70–2.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Another source says "about 5 acres": Colburn 1869, p. 384.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, p. 73.

- ^ Barnewall & Cresswell 1828, p. 723.

- ^ a b Faulkner 2002a, p. 74.

- ^ See the 1895 O.S. map fragment reproduced in this article.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, p. 77. It was 125 feet long and 31 feet wide.

- ^ a b Redman 1848, p. 163.

- ^ See e.g. the artist's impression, 1826.

- ^ In 1820 there already existed:

- The Limehouse Basin of the Limehouse Cut (1768), London's oldest canal (1819 map: white arrow). This canal connected with the River Lea to bring grain to London from Hertfordshire.

- The Limehouse Basin of the West India Docks (1802), which communicated with Limehouse Reach. It is visible in John Fairburn's map of May 7th, 1800; see Embanking of the tidal Thames#Isle of Dogs.

- ^ 1819 Horwood/Fadden map.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Faulkner 2002b, p. 157.

- ^ a b Smith 2013.

- ^ Mayhew 1861, pp. 237–8.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, p. 75.

- ^ See the maps Limehouse Basin in its heyday, 1880 plan, and 1895 O.S.

- ^ a b Faulkner 2002b, p. 152.

- ^ Faulkner 2002b, p. 159.

- ^ a b Wates 1981, pp. 1181–2.

- ^ Historic England 1980.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, p. 77.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, p. 78.

- ^ Fire Brigade Committee 1866, p. 1413.

- ^ Faulkner 2002a, p. 81.

- ^ In 1935 the company's chairman reported it was still 10 acres: Curtis 1935, p. 840. It has since been reduced by the building of Marina Heights along its northern arc and filling in for the Limehouse West development: Faulkner 2002b, p. 158.

- ^ It was intended to make it bigger still, by absorbing part of Limehouse Cut which had its own basin, but this scheme fell through: Colburn 1869, p. 384.

- ^ Caution: Doré drew from memory, and anyway wanted to depict social deprivation not engineering detail. Clearly, the L & B Ry arches are all wrong.

- ^ Curtis 1935, p. 840.

- ^ Colburn 1869, pp. 384–5. "8 feet square, and 3 feet 6 inches thick".

- ^ Hydraulic power had been employed since 1853, the dock being one of the first in London to use it.

- ^ a b Faulkner 2002b, p. 150.

- ^ In contrast to rough ice, got from frozen English canals or ponds, and used by fishmongers and butchers. It might contain sewage. When melted, it sometimes stank: The Times 1868, p. 5.

- ^ The brand leader was the Wenham Lake Ice Company which supposedly got its ice from ultra-clear Lake Wenham, U.S.A. But a lot of ice melted on the transatlantic voyage, and Norway was nearer. In Norway an entrepreneur bought a Norwegian lake and renamed it "Wenham": Blain 2006, pp. 6–7, 9. According to The Times the entrepreneur was none other than the (American) Wenham Lake Ice Company itself; most "Lake Wenham" ice came from Norway The Times 1868, p.5

- ^ Blain 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Saunders 1969, p. 65.

- ^ MOLA 2018.

- ^ Historic England 2015.

- ^ Compton & Faulkner 2006, p. 256.

- ^ Darley 2013, p. 55.

- ^ McKee 1992, p. 199.

- ^ Buxbaum 2014, p. 40.

- ^ Islington Museum 2020.

- ^ Lückes 1884, pp. 69–80.

- ^ Review 1855, pp. 42–3.

- ^ London to Liverpool 1878, p. 228.

- ^ Chambers 1882, pp. 473–5.

- ^ This was known to be grossly inefficient but primitive tankers were liable to capsize (free surface effect) or catch fire.

- ^ The oil was transported from the Baku oilfield to the embarkation port at Batum (Black Sea) by a single-line railway.

- ^ Martell 1887, pp. 1–2, 9, 11, 18.

- ^ Evening Telegraph 1931, p. 6.

- ^ Essex Newsman 1931, p. 4.

- ^ Faulkner 2002b, pp. 151, 148.

- ^ See Janes 1933; Faulkner 2002b, p. 154; Faulkner 2005, p. 63.

- ^ Rather, their parents were paying for their sons to undergo sail training, compulsory in some Baltic nations for men who wanted to get into the merchant marine: see Blue Peter 1934, p. 2; Pskowski 2016, pp. 92–3.

- ^ See External links, below.

- ^ Historic England 1983.

- ^ For example. Edward Weller's prestigious map of 1868, which on this point was out of date.

- ^ Illustrated London News 1857, p. 37.

- ^ Morning Post 1862, p. 3.

- ^ Belfast Morning News 1864, p. 4. There were many such news items in the English and Irish press.

- ^ Illustrated London News 1886, p. 666.

- ^ a b Faulkner 2002b, p. 156.

- ^ An official committee looked into the men's complaint and said the chemical, zinc oxide, was harmless, but still they refused to handle the cargo. The new disciplinary scheme was supported by trade union officials but it was highly unpopular with the rank-and-file, 15% of dock workers having fallen foul of it already. "A spark was all that was needed to inflame the situation" and the Limehouse Basin dispute was that spark. A disciplinary board suspended the Limehouse dock workers for seven days and ordered them to forfeit three months' attendance money. This was felt to be very harsh and fuelled an unofficial strike movement, futilely opposed by trade union officials. The strike spread from London to Liverpool. The Cabinet invoked emergency powers and ordered troops to unload vital cargoes. The strike came to an end because the unofficial movement felt it had demonstrated its powers and because dockers looked forward to a spell of accumulated overtime: Davis 2003, pp. 109–133

- ^ The Sphere 1961, p. 262.

- ^ Lapper 2017.

- ^ Gold 2006.

- ^ Wates 1981, p. 1182.

- ^ Aldous 1981, p. 42.

- ^ Stamp 2011, p. 2. Their Centre Point skyscraper had "associated Seifert inextricably with the excesses of the commercial property boom of the 1960s".

- ^ Knevitt 1986.

- ^ Wates 1986, pp. 1–27.

- ^ Spectrum 1986.

- ^ Powell 1990, p. 135.

- ^ Cook 1990.

- ^ Stevenson & De Moor 1994, p. 888.

- ^ Unlike the rest of the Link, which was made by the top down method to reduce noise to residential properties: Farley & Glass 1994, p. 159

- ^ 1300 tons of steel had to be brought on site.

- ^ a b Glass & Bell 1996, pp. 211–224.

- ^ London Docklands Development Corporation.

- ^ Limehouse Basin 2021.

- ^ Historic England 1950.

- ^ The Guardian 2001.

- ^ Tower Hamlets Council 2009, p. 3-4.

- ^ Cruising Association.

- ^ a b Aquavista.

- ^ The Planning Inspectorate 2020, p. 3.

- ^ London Fire Brigade 2020.

- ^ Glass & Bell 1996, p. 211.

- ^ Canal & River Trust sign displayed southeast Limehouse Basin.

- ^ Canal & River Trust sign displayed southeast Limehouse Basin.

- ^ Canal & River Trust 2021.

- ^ Ward 2015, p. 99.

- ^ Smith 1948, Preface; chapter 1.

- ^ Tyler 2001, pp. 53, 79, 90.

- ^ Glass & Bell 1996, p. 219.

- ^ Killock & Meddens 2005, pp. 1, 16, 19-20. 24.

Sources

[edit]- "A Life-Boat Competition". Illustrated London News. 18 December 1886.

- "A New Life Boat for Greencastle, Londonderry". Belfast Morning News. 5 March 1864.

- "A New Bridge in London's East End". The Sphere. Vol. CCXLVI, no. 3194. London. 19 August 1961.

- Aldous, Tony (1 October 1981). "The changing face of the Thames". Illustrated London News. pp. 38, 42.

- Aquavista. "Limehouse Waterside and Marina". Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- Barnewall, Richard Vaughn; Cresswell, Cressell, Sir (1828). "The King against the Company of Proprietors of the Regent's Canal". Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of King's Bencb. Vol. VI. Butterworth. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blain, Bodil Bjerkvik (2006). Melting Markets: The Rise and Decline Of the Anglo-Norwegian Ice Trade, 1850-1920 (PDF). London School of Economics: Working Papers of the Global Economic History Network (GEHN) No. 20/06. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- Blue Peter (19 June 1934). "Recalling Old-Time Shipbuilders". The Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette.

- Buxbaum, Tim (2014). Icehouses. Shire. ISBN 9780747813002.

- Canal & River Trust (7 August 2021). "Hot weather causes explosion of 'green carpet' of duck weed on London's canals" (PDF) (Press release). Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- Chambers, William and Robert, ed. (29 July 1882). "A Holiday Cruise". Chambers Journal of Popular Literature, Science and Art. 4th. Vol. XXIX. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Colburn, Zerah, ed. (1869). "Limehouse Basin Improvement". Engineering: An Illustrated Weekly Journal. VII. London: 384–5. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Colquhoun, Patrick (1800). Treatise on the Commons and Police of the River Thames. London: Joseph Mawman. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Compton, Hugh; Faulkner, Alan (2006). "The Cumberland Market Branch of the Regent's Canal" (PDF). Journal of the Railway & Canal Historical Society. 35 (194): 254–261. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Cook, Stephen (8 October 1990). "Keeping afloat in the docks housing market: Will lower interest rates lift the gloom in Docklands? Stephen Cook reports on the desperate devices of developers to sell homes". The Guardian.

- Cruising Association. "CA House". Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Curtis, Wilfrid Henry (1935). "Canals". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. 83 (4313): 837–857. JSTOR 41360513.

- Darley, Peter (2013). Camden Goods Station Through Time. Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-2204-0.

- Davis, Colin J (2003). "The 1948 London Dock Strike". Waterfront Revolts: New York and London Dockworkers 1949-61. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02878-3. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- Fire Brigade Committee (1866). "Report". Minutes of Proceedings of the Metropolitan Board of Works. London: 1412–3. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Farley, K.R.; Glass, P.R. (1994). "The construction of Limehouse Link tunnel". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Limehouse. 105: 153–164. doi:10.1680/itran.1994.26790.

- Faulkner, Alan H (2002a). "The Regent's Canal Dock, Part 1" (PDF). Journal of the Railway & Canal Historical Society. 34 (2): 70–82. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- Faulkner, Alan H (2002b). "The Regent's Canal Dock, Part 2" (PDF). Journal of the Railway & Canal Historical Society. 34 (3): 148–159. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- Faulkner, Alan (2005). The Regent's Canal — London's Hidden Waterway. Burton-on-Trent: Waterways World. ISBN 1-870002-59-8.

- Galloway, James A.; Keene, Derek; Murphy, Margaret (1996). "Fuelling the city: production and distribution of firewood and fuel in London's region, 1290-1400". Economic History Review. XLIX (3): 447–472. JSTOR 2597759.

- Glass, P.R.; Bell, B.C. (1996). "Limehouse Link cut and cover tunnel: design and construction through Limehouse Basin". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Maritime & Energy. 118 (4): 211–225. doi:10.1680/iwtme.1996.28986.

- Gold, Mary (1 December 2006). "A touch of the Dutch; Thames gateway". The Times.

- Google Maps (Limehouse Basin) (Map). Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Greater variety in children's entertainment". Essex Newsman. 28 December 1931.

- Hausman, William J. (1977). "Size and Profitability of English Colliers in the Eighteenth Century". The Business History Review. 51 (4). Harvard: 460–473. doi:10.2307/3112880. JSTOR 3112880. S2CID 154377002.

- Historic England (29 December 1950). "CHURCH OF ST ANNE, LIMEHOUSE PARISH CHURCH, COMMERCIAL ROAD, E14". Historic England. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- Historic England (9 May 1980). "RAILWAY VIADUCT TO NORTH OF REGENTS CANAL DOCK BETWEEN AND INCLUDING BRANCH ROAD BRIDGE AND LIMEHOUSE CUT UP TO THREE COLT STREET". Historic England. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Historic England (1 July 1983). "BRITISH WATERWAYS CUSTOMS HOUSE ON WEST QUAY OF REGENT'S CANAL DOCK ENTRANCE". Historic England. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Historic England (28 October 2015). "A subterranean commercial ice-well (City of Westminster), Park Crescent, W1". Historic England. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- "Homes 2001: National HomeBuilder Design Awards 2001: Building on solid foundations: CATEGORY 2: Best Apartment Building". The Guardian. 6 April 2001. p. 9.

- Hunter, Jefferson (2019). "Reading the Regent's Canal". The Hopkins Review. 12 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 318–334. doi:10.1353/thr.2019.0051. S2CID 203301653.

- Janes, Norman Thomas (1933). "Three sailing ships in Regent's Canal Dock, 1933, discharging timber". National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- Killock, Douglas; Meddens, Frank (2005). "Pottery as plunder: a 17th-century maritime site in Limehouse, London". Post-Medieval Archaeology. 39 (1): 1–91. doi:10.1179/007943205X53363. S2CID 162245620. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- Knevitt, Charles (21 April 1986). "Owen signs docks protest". The Times.

- Lapper, Richard (1 February 2017). "Does London's Limehouse still offer good value to homebuyers?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- "Lions and Tigers Coming to Town". Evening Telegraph. 18 December 1931.

- "Life-boats". Illustrated London News. 11 July 1857.

- "Life Boats for Spain". Morning Post. 19 April 1862.

- London Docklands Development Corporation. "Limehouse Link" (PDF). LDDC History. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- London Fire Brigade (2020). "Stephen Maynard remembered". Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- "London to Liverpool by water". The Bazaar, Exchange and Mart, and Journal of the Household. Vol. XIX. London. 9 October 1878. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Lückes, Eva C.E. (1884). Lectures on General Nursing Delivered to the Probationers of the London Hospital Training School for Nurses. London: Kegan Paul, Trench. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- McKee, Francis (1992). "Ice Cream and Immorality". In Walker, Harlan (ed.). Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking 1991: Public Eating. Prospect Books. ISBN 0-907325-47-5. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Martell, B. (1887). "On the carriage of petroleum in bulk on over-sea voyages". Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects. XXIII. London: 1-24 and Plate I Figs. 1-17. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Mayhew, Henry (1861). London Labour and the London Poor. The great metropolis. II. Vol. III. London: Griffin, Bohn. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- MOLA (28 December 2018). "18th century Ice House re-discovered beneath the streets of Marylebone". Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- Powell, Kenneth (24 May 1990). "Basins, Docks and Waterways". Country Life.

- Pskowski, Rebecca Prentiss (2016). "The Sailing School Vessels Act of 1982 and the Legal Status of Sail Trainees". Tulane Maritime Law Journal. 41 (1): 87–140. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- Redman, John Baldry (1848). "Remarks on the Formation of Entrances to Wet and Dry Docks, situated upon a Tideway; illustrated by the principal examples in the Port of London". Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. VII. London: 159–184+drawings. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Review (1855). "On Benumbing Cold as a Preventive of Pain and Inflammation from Surgical Operations etc. By JAMES ARNOTT, M.D. pp. 24. London, 1854". The Lancet. I: 42–3. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Saumarez Smith, Charles (29 March 1990). "Books: It's modern. It's exciting. Just tell me where I can buy a pint of milk: Charles Saumarez Smith reviews London Docklands: An Architectural Guide by Elizabeth Williamson and Nikolaus Pevsner". The Observer.

- Saunders, Ann (1969). Regent's Park: A Study of the Development of the Area from 1068 to the Present Day. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

- Smith, Emma (1948). Maidens' Trip: A Wartime Adventure on the Grand Union Canal (2011 ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. Kindle Edition.

- Smith, Tim (1993). "Regent's Canal Dock". GLIAS. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Smith, Tim R (2013). "The Limehouse Basin Accumulator Tower". GLIAS. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Spectrum (6 June 1986). "The Limehouse Basin". The Times.

- Stamp, Gavin (2011). "Seifert, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online. Oxford University Press.

- Stevenson, M.C.; De Moor, E.K. (1994). "Limehouse link cut-and cover tunnel: Design and performance". International conference on soil mechanics and foundation engineering (PDF). New Delhi. pp. 887–890. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tan, Elaine S. (2009). "Market Structure and the Coal Cartel in Early Nineteenth-Century England". The Economic History Review. 62 N.S (2): 350–365. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2008.00441.x. JSTOR 20542915. S2CID 154417730.

- "The Ice Trade". The Times. 11 September 1868.

- "The Icy Past of Regent's Canal". Islington Museum. 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- The Planning Inspectorate (5 May 2020). "Appeal Ref: APP/E5900/W/19/3235605 Limehouse Marina, Limehouse Basin, London E14 8EG". Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- Tower Hamlets Council (2009). "Narrow Street Conservation Area" (PDF). Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Tyler, Kieron (2001). "The excavation of an Elizabethan/Stuart waterfront site on the north bank of the River Thames at Victoria Wharf, Narrow Street, Limehouse, London E14". Post-Medieval Archaeology. 35 (1): 53–95. doi:10.1179/pma.2001.003. S2CID 161733828.

- Ville, Simon (1986). "Total Factor Productivity in the English Shipping Industry: The North-East Coal Trade, 1700-1850". The Economic History Review. 39 (3). Wiley: 355–370. doi:10.2307/2596345. JSTOR 2596345.

- Wade, E. (1871). "Ice". The Food Journal. London: J.M. Johnson: 320–4. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- Ward, Laurence (2015). The London County Council Bomb Damage Maps 1939-1945. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51825-0.

- Wates, Nick (24 June 1981). "Vital rapid transit route to Docklands threatened" (PDF). Architects' Journal. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- Wates, Nick, ed. (1986). The Limehouse Petition (PDF). London: The Limehouse Development Group in association with the Town and Country Planning Association. ISBN 0-902797-12-3. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- "Three sailing ships in Regent's Canal Dock, 1933, discharging timber", painting by Norman Thomas Janes

- "Barging Through London", 1924 silent travelogue showing Limehouse Basin with sailing ships and horse-drawn barges

- British Pathé silent film (1926) showing sailing ships at Limehouse Basin (0:12—0:50)

- Video: how to enter today's Limehouse Basin from the Thames with your vessel

![The north quay jetty drawn by Gustave Doré.[40] Notice hydraulic cranes.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/Bpt6k10470488_f98.jpg/586px-Bpt6k10470488_f98.jpg)