Portal:Mathematics

The Mathematics Portal

Mathematics is the study of representing and reasoning about abstract objects (such as numbers, points, spaces, sets, structures, and games). Mathematics is used throughout the world as an essential tool in many fields, including natural science, engineering, medicine, and the social sciences. Applied mathematics, the branch of mathematics concerned with application of mathematical knowledge to other fields, inspires and makes use of new mathematical discoveries and sometimes leads to the development of entirely new mathematical disciplines, such as statistics and game theory. Mathematicians also engage in pure mathematics, or mathematics for its own sake, without having any application in mind. There is no clear line separating pure and applied mathematics, and practical applications for what began as pure mathematics are often discovered. (Full article...)

Featured articles –

Selected image –

Good articles –

Did you know (auto-generated) –

- ... that in the aftermath of the American Civil War, the only Black-led organization providing teachers to formerly enslaved people was the African Civilization Society?

- ... that Ukrainian baritone Danylo Matviienko, who holds a master's degree in mathematics, appeared as Demetrius in Britten's opera A Midsummer Night's Dream at the Oper Frankfurt?

- ... that owner Matthew Benham influenced both Brentford FC in the UK and FC Midtjylland in Denmark to use mathematical modelling to recruit undervalued football players?

- ... that record-setting airplane spinner Catherine Cavagnaro is also a professional mathematician?

- ... that after Florida schools banned 54 mathematics books, Chaz Stevens petitioned that they also ban the Bible?

- ... that a folded paper lantern shows that certain mathematical definitions of surface area are incorrect?

- ... that the word algebra is derived from an Arabic term for the surgical treatment of bonesetting?

- ... that two members of the French parliament were killed when a delayed-action German bomb exploded in the town hall at Bapaume on 25 March 1917?

More did you know –

- ...that as of April 2010 only 35 even numbers have been found that are not the sum of two primes which are each in a Twin Primes pair? ref

- ...the Piphilology record (memorizing digits of Pi) is 70000 as of Mar 2015?

- ...that people are significantly slower to identify the parity of zero than other whole numbers, regardless of age, language spoken, or whether the symbol or word for zero is used?

- ...that Auction theory was successfully used in 1994 to sell FCC airwave spectrum, in a financial application of game theory?

- ...properties of Pascal's triangle have application in many fields of mathematics including combinatorics, algebra, calculus and geometry?

- ...work in artificial intelligence makes use of swarm intelligence, which has foundations in the behavioral examples found in nature of ants, birds, bees, and fish among others?

- ...that statistical properties dictated by Benford's Law are used in auditing of financial accounts as one means of detecting fraud?

Selected article –

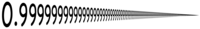

Image credit: User:Melchoir |

The real number denoted by the recurring decimal 0.999… is exactly equal to 1. In other words, "0.999…" represents the same number as the symbol "1". Various proofs of this identity have been formulated with varying rigour, preferred development of the real numbers, background assumptions, historical context, and target audience.

The equality has long been taught in textbooks, and in the last few decades, researchers of mathematics education have studied the reception of this equation among students, who often reject the equality. The students' reasoning is typically based on one of a few common erroneous intuitions about the real numbers; for example, a belief that each unique decimal expansion must correspond to a unique number, an expectation that infinitesimal quantities should exist, that arithmetic may be broken, an inability to understand limits or simply the belief that 0.999… should have a last 9. These ideas are false with respect to the real numbers, which can be proven by explicitly constructing the reals from the rational numbers, and such constructions can also prove that 0.999… = 1 directly. (Full article...)

| View all selected articles |

Subcategories

Algebra | Arithmetic | Analysis | Complex analysis | Applied mathematics | Calculus | Category theory | Chaos theory | Combinatorics | Dynamical systems | Fractals | Game theory | Geometry | Algebraic geometry | Graph theory | Group theory | Linear algebra | Mathematical logic | Model theory | Multi-dimensional geometry | Number theory | Numerical analysis | Optimization | Order theory | Probability and statistics | Set theory | Statistics | Topology | Algebraic topology | Trigonometry | Linear programming

Mathematics | History of mathematics | Mathematicians | Awards | Education | Literature | Notation | Organizations | Theorems | Proofs | Unsolved problems

Topics in mathematics

| General | Foundations | Number theory | Discrete mathematics |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Algebra | Analysis | Geometry and topology | Applied mathematics |

Index of mathematics articles

| ARTICLE INDEX: | |

| MATHEMATICIANS: |

Related portals

WikiProjects

![]() The Mathematics WikiProject is the center for mathematics-related editing on Wikipedia. Join the discussion on the project's talk page.

The Mathematics WikiProject is the center for mathematics-related editing on Wikipedia. Join the discussion on the project's talk page.

In other Wikimedia projects

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

More portals

- ^ Coxeter et al. (1999), p. 30–31; Wenninger (1971), p. 65.