Propinquity

In social psychology, propinquity (/prəˈpɪŋkwɪtiː/; from Latin propinquitas, "nearness") is one of the main factors leading to interpersonal attraction.

It refers to the physical or psychological proximity between people. Propinquity can mean physical proximity, a kinship between people, or a similarity in nature between things ("like-attracts-like"). Two people living on the same floor of a building, for example, have a higher propinquity than those living on different floors, just as two people with similar political beliefs possess a higher propinquity than those whose beliefs strongly differ. Propinquity is also one of the factors, set out by Jeremy Bentham, used to measure the amount of (utilitarian) pleasure in a method known as felicific calculus.

Propinquity effect

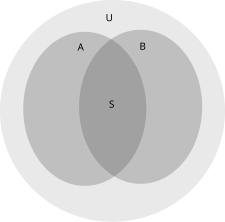

[edit]The propinquity effect is the tendency for people to form friendships or romantic relationships with those whom they encounter often, forming a bond between subject and friend. Workplace interactions are frequent and this frequent interaction is often a key indicator as to why close relationships can readily form in this type of environment.[1] In other words, relationships tend to form between those who have a high propinquity. It was first theorized by psychologists Leon Festinger, Stanley Schachter, and Kurt Back in what came to be called the Westgate studies conducted at MIT (1950).[2] The typical Euler diagram used to represent the propinquity effect is shown below where U = universe, A = set A, B = set B, and S = similarity:

The sets are basically any relevant subject matter about a person, persons, or non-persons, depending on the context. Propinquity can be more than just physical distance. Residents of an apartment building living near one of the building's stairways, for example, tend to have more friends from other floors than those living further from the stairway.[2] The propinquity effect is usually explained by the mere exposure effect, which holds that the more exposure a stimulus gets, the more likeable it becomes. There is a requirement for the mere exposure effect to influence the propinquity effect, and that is that the exposure is positive. If the resident has repeatedly negative experiences with a person then the propinquity effect has a far less chance of happening (Norton, Frost, & Ariely, 2007).[3]

In a study on interpersonal attraction (Piercey and Piercey, 1972), 23 graduate psychology students, all from the same class, underwent 9 hours of sensitivity training in two groups. Students were given pre- and post-tests to rate their positive and negative attitudes toward each class member. Members of the same sensitivity training group rated each other higher in the post-test than they rated members of the other group in both the pre- and post-test, and members of their own group in the pre-test. The results indicated that the 9 hours of sensitivity training increased the exposure of students in the same group to each other, and thus they became more likeable to each other.[4]

Propinquity is one of the effects used to study group dynamics. For example, there was a British study done on immigrant Irish women to observe how they interacted with their new environments (Ryan, 2007). This study showed that there were certain people with whom these women became friends much more easily than others, such as classmates, workplace colleagues, and neighbours as a result of shared interests, common situations, and constant interaction. For women who still felt out of place when they began life in a new place, giving birth to children allowed for different ties to be formed, ones with other mothers. Having slightly older children participating in activities such as school clubs and teams also allowed social networks to widen, giving the women a stronger support base, emotional or otherwise.[5]

Types

[edit]Various types of propinquity exist: industry/occupational propinquity, in which similar people working in the same field or job tend to be attracted to one another;[6] residential propinquity, in which people living in the same area or within neighborhoods of each other tend to come together;[7] and acquaintance propinquity, a form of proximity in existence when friends tend to have a special bond of interpersonal attraction. Many studies have been performed in assessing various propinquities and their effect on marriage.

Virtual propinquity

[edit]The introduction of instant messaging and video conferencing has reduced the effects of propinquity. Online interactions have facilitated instant and close interactions with people despite a lack of material presence. This allows a notional "virtual propinquity" to work on virtual relationships where people are connected virtually.[8] However, research that came after the development of the internet and email has shown that physical distance is still a powerful predictor of contact, interaction, friendship, and influence.[9]

In popular culture

[edit]This section may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (August 2021) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

William Shakespeare's

King Lear, Act 1 Scene 1 Page 5

LEAR:

'Let it be so. Thy truth then be thy dower.

For by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate and the night,

By all the operation of the orbs

From whom we do exist and cease to be—

Here I disclaim all my paternal care,

Propinquity, and property of blood,

And as a stranger to my heart and me

Hold thee from this for ever. The barbarous Scythian,

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

Be as well neighbored, pitied, and relieved

As thou my sometime daughter.'

"Love is a Science", a 1959 short story by humorist Max Shulman, features a girl named Zelda Gilroy assuring her science lab tablemate, Dobie Gillis, that he would eventually come to love her through the influence of propinquity, as their similar last names would put them in proximity throughout school. "Love is a Science" was adapted into a 1959 episode of the Shulman-created TV sitcom The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, featuring Dobie as its main character and Zelda as a semi-regular, and a 1988 made-for-TV movie based on the series, Bring Me the Head of Dobie Gillis, portrayed Dobie and Zelda as being married.

"Propinquity (I've Just Begun To Care)" is a song by Mike Nesmith. It was first recorded by Nesmith in 1968 while he was with The Monkees, though this version was not released until the 1990s. The first released version was by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band on their album Uncle Charlie & His Dog Teddy, and Nesmith released a new version on his solo album Nevada Fighter.

On page 478 of Jonathan Franzen's 2010 novel Freedom, Walter attributes his inability to stop having sex with Lalitha to their "daily propinquity".

On page 150 in Michael Ondaatje's novel The English Patient, "He said later it was propinquity. Propinquity in the desert. It does that here, he said. He loved the word – the propinquity of water, the propinquity of two or three bodies in a car driving the Sand Sea for six hours."

In Ian Fleming's 1957 James Bond novel Diamonds Are Forever, Felix Leiter tells Bond "Nothing propinks like propinquity."

In William Faulkner's 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom!, Rosa, in explaining to Quentin why she agreed to marry Sutpen, states, "I don't plead propinquity: the fact that I, a woman young and at the age for marrying and in a time when most of the young men whom I would have known ordinarily were dead on lost battlefields, that I lived for two years under the same roof with him."

In Ryan North's webcomic Dinosaur Comics, T-Rex discusses propinquity.[10]

In the P. G. Wodehouse novel Right Ho, Jeeves, Bertie asks, "What do you call it when two people of opposite sexes are bunged together in close association in a secluded spot meeting each other every day and seeing a lot of each other?" to which Jeeves replies, "Is 'propinquity' the word you wish, sir?" Bertie: "It is. I stake everything on propinquity, Jeeves."

In Ernest Thompson Seton's short story "Arnaux: the Chronicle of a Homing Pigeon," published in Animal Heroes (1905): "Pigeon marriages are arranged somewhat like those of mankind. Propinquity is the first thing: force the pair together for a time and let nature take its course."

See also

[edit]- Psychological distance – degree of a person's detachment from emotional involvement

- Human bonding – Process of development of a close, interpersonal relationship

- Proxemics – Study of human use of space and the effects that population density has on behavior

- Westermarck effect – Hypothesis that those who grow up together become desensitized to sexual attraction

- Allen curve – Graphical representation of human communication

References

[edit]- ^ Marvin, D. M., (1919). Occupational propinquity as a factor in marriage selection, University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ a b Festinger, L., Schachter, S., Back, K., (1950) "The Spatial Ecology of Group Formation", in L. Festinger, S. Schachter, & K. Back (eds.), Social Pressure in Informal Groups, 1950. Chapter 4.

- ^ Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. (2007). Less is more: The lure of ambiguity, or why familiarity breeds contempt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 97-105.

- ^ Piercy, F. P., & Piercy, S. K. (1972). Interpersonal attraction as a function of propinquity in two sensitivity groups. Psychology: A Journal of Human Behavior, 9(1), 27–30.

- ^ Ryan, Louise (2007). "Migrant Women, Social Networks and Motherhood: The Experiences of Irish Nurses in Britain". Sociology. 41 (2): 295–312. doi:10.1177/0038038507074975.

- ^ Martin, Donald M. (1918). "Occupational Propinquity as a Factor in Marriage Selection," Vol 16, No.123, pp. 131–150. American Statistical Association.

- ^ Bossard, James H.S.(1932). "Residential Propinquity as a Factor in Marriage Selection," Vol 38, No.2, pp. 219–224. American Journal of Sociology.

- ^ Perry, Martha W.(2006). Instant messaging: virtual propinquity for health promotion networking, 211–2

- ^ Latane, B., Liu, J. H., Nowak, A., Bonevento, M., & Zheng, L. (1995). Distance matters: Physical space and social impact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(8), 795–805.

- ^ "Dinosaur Comics!".

External links

[edit]- Propinquity Effect

- Human Mate Selection – An Exploration of Assortive Mating Preferences – (has two pages of propinquity studies)