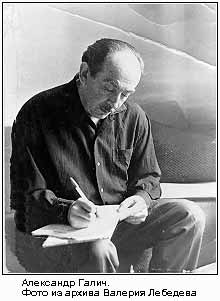

Alexander Galich (writer)

Alexander Galich | |

|---|---|

| Александр Аркадьевич Галич | |

| |

| Born | Alexander Aronovich Ginzburg 19 October 1918 Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipro), Ukraine |

| Died | 15 December 1977 (aged 59) Paris, France |

| Citizenship | Soviet Union |

| Occupation(s) | poet, screenwriter, playwright, singer-songwriter, and dissident |

| Known for | his songs and participation in Soviet dissident movement |

Alexander Arkadievich Galich (Russian: Алекса́ндр Арка́дьевич Га́лич, born Alexander Aronovich Ginzburg, 19 October 1918 – 15 December 1977) was a Soviet poet, screenwriter, playwright, singer-songwriter, and dissident.

Biography[edit]

Galich is a pen name, an abbreviation of his last name, first name, and patronymic: Ginzburg Alexander Arkadievich. He was born on 19 October 1918 in Ekaterinoslav (then Dnipropetrovsk and now Dnipro), Ukraine, into a family of Jewish intellectuals. His father, Aron Samoilovich Ginzburg, was an economist, and his mother, Fanni Borisovna Veksler, worked in a music conservatory. For most of his childhood he lived in Sevastopol. Before World War II, he entered the Gorky Literary Institute, then moved to Konstantin Stanislavski's Operatic-Dramatic Studio, and then to the Studio-Theatre of Alexei Arbuzov and Valentin Pluchek (in 1939).

He wrote plays and screenplays, and in the late 1950s, he started to write songs and sing them accompanying himself on his guitar. Influenced by the Russian city romance tradition and the art of Alexander Vertinsky, Galich developed his own voice within the genre. He practically single-handedly created the genre of "bard song". Many of his songs spoke of the Second World War and the lives of concentration camp inmates—subjects which Vladimir Vysotsky also began tackling at around the same time. They became popular with the public and were made available via magnitizdat.

His first songs, though rather innocent politically, nevertheless were distinctly out of tune with the official Soviet aesthetics. They marked a turning point in Galich's creative life, since before this, he was a quite successful Soviet man of letters. This turn was also brought about by the aborted premiere of his play Matrosskaya Tishina written for the newly opened Sovremennik Theatre. The play, already rehearsed, was banned by censors, who claimed that the author had a distorted view of the role of Jews in the Great Patriotic War. This incident was later described by Galich in the story Generalnaya Repetitsiya (Dress Rehearsal).

Galich's increasingly sharp criticism of the Soviet regime in his music caused him many problems. After it was established in 1970, the dissident Committee on Human Rights in the USSR included Galich as an honorary member.[1] In 1971, he was expelled from the Soviet Writers' Union, which he had joined in 1955. In 1972, he was expelled from the Union of Cinematographers. That year he became baptized in the Eastern Orthodox Church by Alexander Men.

Galich was forced to emigrate from the Soviet Union in 1974. He initially lived in Norway for one year, where he made his first recordings outside of the USSR. These were broadcast by him on Radio Liberty. His songs critical towards the Soviet government became immensely popular in the underground scene in the USSR. He later moved to Munich and finally to Paris.

On the evening of 15 December 1977, he was found dead by his wife, clutching a Grundig stereo recording antenna plugged into a power socket. While his death was declared to be an accident,[2][3] no one witnessed the exact circumstances of his death.[4] The results of the official investigation were not publicly released by French police.

According to his daughter Alena Galich-Arkhangelskaya, Galich was murdered by the KGB.[3][5] Journalist and KGB agent Leonid Kolosov claimed that KGB chairman Yuri Andropov personally authorized a mission to bring Galich back to the USSR, promising a restoration of citizenship and artistic freedom.[6] But it remains unknown if KGB agents ever made him such an offer.

In 1988, he was posthumously re-instated into the Writers' and Cinematographers' Unions. In 2003, the first memorial plaque for Galich was put up on a building in Akademgorodok (Novosibirsk) where he performed in 1968. That same year, the Alexander Galich Memorial Society was founded.

Music[edit]

Alexander Galich, like most bards, had a fairly minimal musical background. He played his songs on a seven string Russian guitar, which was fairly standard at the time. He often wrote in the key of D minor, relying on very simple chord progressions and fingerpicking techniques. He had basic piano playing skills as well.

Galich had a signature cadence that he would usually play at the conclusion of a song (and sometimes at the beginning). He would play the D minor chord toward the top of the fretboard (fret position 0XX0233, thickest to thinnest string, open G tuning), then slide down the fretboard to a higher voiced D minor (0 X X 0 10 10 12).

Bibliography[edit]

- Alexander Galich. Songs and Poems (translated and edited by Gerald Stanton Smith) - Ann Arbor: Ardis, April 1983, 203 pages ISBN 0882339524 ISBN 978-0882339528

- Richard A. Zavon. The Dilemma of Soviet Man: A Study of the Underground Lyrics of Bulat Okudzhava and Aleksandr Galich. - U.S. Army Institute for Advanced Russian and East European Studies, 1977, 128 pages

- Alexander Galich. Dress Rehearsal: A Story in Four Acts and Five Chapters (translated and edited by Maria R. Bloshteyn) - Slavica Pub, February 2009, 221 pages, ISBN 0893573388 ISBN 978-0893573386

Discography[edit]

- «A whispered cry» — sung in Russian by Alexander Galitch. Recorded in 1974 at The Arne Bendiksen Studios, Oslo, Norway.(1974)

- «Unpublished songs of Russian bards» Produced by Hed-arzi ltd., Israel (1974)

- «Galich in Israel — Holocaust Songs Russian» (Live Concert version, 1975). «GALTON» Studios. Manufactured By Gal-Ron (Israel).

- «Alexander Galich — Cheerful Talk» (Live Concert version, 1975). «GALTON» Studios (Ramat-Gan), 220390, STEREO 5838. Manufactured By Gal-Ron (Israel).

- «Alexander Galich — The laughter through the tears». Fortuna, Made in USA (1981-?)

- Audio records of Galich reading his poetry, 2000

Notes[edit]

- ^ Alexeyeva, Lyudmila (1987). Soviet Dissent: Contemporary Movements for National, Religious, and Human Rights. Carol Pearce (trans.). Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press. p. 293. ISBN 0-8195-6176-2.

- ^ Mikhail Aronov. Alexander Galich. Full Biography. Moscow: NLO, 2012, 912 pages. ISBN 978-5-86793-931-1, pages 817-818, 820-822 and 827.

- ^ a b Alena Galich: «My Father Was Murdered!» interview by Moskovskij Komsomolets, 10 January 2013 (in Russian)

- ^ see biography on peoples.ru(Russian)

- ^ Actress Alena Galich-Arkhangelskaya, Daughter of Alexander Galich interview by the Gordon's Boulevard newspaper, № 42 (442), 15 October 2013 (in Russian)

- ^ Undercover lives : Soviet spies in the cities of the world. Helen Womack. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. 1998. ISBN 0-297-84126-2. OCLC 40877594.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

References[edit]

- Alexandr Galich, Songs and poems; transl. by Gerald Stanton Smith, Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1983, ISBN 0-88233-952-4

External links[edit]

- (in English) Alexander Galich's bio

- (in Russian) Galich page on the bard.ru site

- (in Russian) Alexander Galich - video

- Poem "Experience of nostalgia" by Galich by actress Lada Negrul

- 1918 births

- 1977 deaths

- Writers from Sevastopol

- Soviet Jews

- Soviet dramatists and playwrights

- Soviet male writers

- 20th-century Russian male writers

- Soviet screenwriters

- Russian male screenwriters

- Soviet male singer-songwriters

- Soviet singer-songwriters

- Seven-string guitarists

- Soviet poets

- Ukrainian male poets

- Jewish poets

- Russian-language poets

- Soviet dissidents

- Converts to Eastern Orthodoxy from Judaism

- Soviet expellees

- Soviet emigrants to Norway

- Soviet emigrants to Germany

- Soviet emigrants to France

- Accidental deaths by electrocution

- Burials at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery

- Russian male dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century guitarists

- 20th-century Russian male singers

- Maxim Gorky Literature Institute alumni

- 20th-century Russian screenwriters

- Accidental deaths in France

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers